I started working at Zuni Café in 2015, approximately a year and a half after the passing of legendary chef-owner Judy Rodgers. It was still a time full of grief, and Judy’s spirit was as palpable as the lingering, heady aroma from the wood-fired oven outside her iconic Bay Area restaurant. Her book, The Zuni Café Cookbook, published in 2002 by W. W. Norton, occupied a prideful place near the entrance. Above it was a framed photo of Judy, hair tied up, smiling in her chef’s whites as if she were watching, insisting that diners and even we as workers deserve the best. After their first month, every new cook would receive a copy of the book from the chef de cuisine, and it immediately became a bible-like resource for me.

Since opening in 1979, Zuni has been the vibey, beating heart of San Francisco dining—an institution of Californian and American cookery. It’s a social hub that you can pop into on a whim for a cocktail and a tower of shoestring fries with friends; a long, lazy lunch; or a special occasion, like my postnuptial meal. After I got married in 2017 at San Francisco City Hall down the street, I came to Zuni for lunch. They played the “Wedding March” as we walked in, and I’m not one to get all weepy in public, but that moment got me. (So did the tiny oysters Juanito shucked and delivered to our table, and the sour cherry and chocolate cake Chef Annie made especially for us.) It’s an award-winning restaurant, known around the world, but as far as I know, Zuni has never really sought out any accolades and has never even had a PR team.

When I first received The Zuni Café Cookbook, I would make it a point to prepare for my shifts at home by reading a section, any section, usually at my dining table inside the little nook of the bay window. Then I’d bike down the Wiggle, a crisscrossing, bike-friendly route that avoids the hilliest hills and that would take me through the Lower Haight, past Hayes Valley, and onto Market Street: the main drag through the densest part of San Francisco, and the street where Zuni lives.

I was pretty exclusively working night shifts back then, and I had to go in for my eight-hour shift at 3:30 p.m. Once I clocked in and saw the already full dining room full of late-lunch diners, the reality of working restaurant service at a very busy restaurant would snap into focus. The cookbook’s wisdom came into full effect during a rush, and sometimes I was more intentional with my self-prescribed homework assignment. On my first day working the salad station solo, I turned to that section of the book and was filled with anxiety when I read that Judy had nicknamed the Caesar salad “seizure salad”—because so many orders come in at a time that you just might feel like you’re having a seizure. But it also felt like Judy was shadowing me as I delicately handled the mesclun lettuce and rubbed just enough garlic on the long, curvy croutons we made from the crusts of day-old levain bread.

After getting over that “seizure,” I worked at Zuni for several more years. It was Judy’s words that got me excited to learn, in real time, at her restaurant and through her book. When she wrote about Zuni’s mantra of optimizing ingredients based on their individual condition, taste, and evolution over the seasons instead of diluting or ignoring them by, say, preparing all Early Girl tomatoes or all fingerling potatoes the same way, I was intrigued. I knew that some ingredients got special attention like that. But I didn’t know what diluting an ingredient actually meant, let alone optimizing it. I would read about techniques or dishes in the book and eagerly wait for their debut in the restaurant. I couldn’t wait to taste Judy’s “favorite dessert” of fried figs with whipped cream, raspberries, and honey (page 459) that would surely appear in late summertime, during figs’ second season of the year. When the kitchen’s walk-in coolers were already bursting at the latches, crisping up choice produce to help move it made more sense than devouring it raw. Abundance was an opportunity for more luxury.

Throughout my years as a line cook, my peers and I would reference the book like it was a portal to Judy’s past consciousness that we could use in our present. We’d use the cookbook to try to better understand this big old weird restaurant that we loved working at; like, why were “gizmos” besides the robot coupe not used in the kitchen while we deployed an iron rod with a spiral, sorceress-like handle to guide the famed chickens and thin-crust pizzas with tomato sauce and ricotta salata in the wood-fired brick oven? Why was this place called Zuni anyway? Why did the menu HAVE to change twice a day? Judy’s words also simply made me feel comfortable in a strange new kitchen. I started out cooking with her time-honored tools and eventually moved to sitting in her chef chair, writing menus, when I became a sous chef and shared the added privilege of deciding what we were serving.

Of course, The Zuni Café Cookbook is not merely an employee handbook. In one pot, it’s a beautiful chronicle of a restaurant and the dishes that represent the wood-fired oven of California cuisine, as well as Italian and French cooking, through a late 20th-century American perspective that has influenced so many chefs, food writers, and home cooks. Like Chez Panisse, Zuni is a hub for food talent with a far-reaching roster. Food writer and pastry chef David Lebovitz worked there in the early ’80s; chef Brandon Jew of the San Francisco restaurant Mister Jiu’s worked there in the early 2000s; and it’s been a favorite cookbook party location for authors from David Tanis and Gabriela Cámara to JR Ryall and Russell Moore.

Published 20 years ago, it was edited by the notable, late Maria Guarnaschelli, who Judy credited as championing “an ambitious book [she’d] never have had the vision to compose on [her] own.” Photographed by Andrea Gentl and Martin Hyers, pioneers in the food and travel photography world who have gone on to shoot iconic books like Tartine: A Classic Revisited and the more recent Via Carota, their work in the cookbook captures the essence of Zuni before anyone and everyone had a camera in their pocket. Gerald Asher, who was wine editor of Gourmet for 30 years, “added heart” with his wine notes. The Zuni Café Cookbook embodies all that you might expect from a “restaurant cookbook,” but it is unique because Judy artfully illustrates instead of simply describing her culinary journey, starting with an “unassumingly delicious ham sandwich” made for her by Jean Troisgros, one of France’s most influential 20th-century chefs.

Judy was 16 years old when she embarked on an impressive culinary journey—a ping-pong match between California and Europe that feels like a mixture of luck and fate. On a high school exchange, that ham sandwich turned into a year-long stage during which she recorded notes and recipes, all under the wing of Jean and his brother, Pierre, at their restaurant Les Frères Troisgros in Roanne. Later, after college in Berkeley, California, with those culinary notes in tow, Alice Waters gave her the opportunity to work lunch in the kitchen at Chez Panisse.

France beckoned to Judy again, this time in the southwest region of Landes, where she landed another stage in tiny “café-bar-restaurant-tabac-post office” called L’Estanquet . After that, Judy worked with food writer and friend of Waters Marion Cunningham in the kitchen at the Union Hotel in Benicia, California, where they focused on New American cookery. By 1983, Judy was back in Europe, this time to scour the Italian culinary scene, tasting and taking vigorous notes. All of these experiences were extremely important for her when she came back to California with the goal of implementing them in her own kitchen. In 1987, Judy was asked to be chef at Zuni Café by its then co-owners Billy West and Vince Calcagno.

From the book’s opening page, Judy’s description of the restaurant is vivid and romantic. She sets the scene of the establishment that sits open and as vibrant as ever today at the corner of Market Street and Rose Alley (its nickname now is Rosé Alley) in what is socially, if not geographically, the center of the city, on the edge of the Hayes Valley neighborhood. She writes, “Zuni Café occupies an unlikely triangular space. . . . During the day the natural light is stunning, and after dusk the space glows like a jeweled box from two blocks away. The restaurant feels barely contained. It’s not fancy, there are no expensive finishes, just handsome spaces.”

Judy’s initial encounter with the restaurant sparks as she describes it: “I took in the space and imagined you could eat as simply or as grandly as you wanted in this setting, and that the food would only be a part of the seduction.”

Cookbook author and pastry chef David Lebovitz had an astute observation about Judy and her writing too: “One thing I remember about Judy is that she was always moving. Nothing was wasted, not even a movement,” he says. “She was either going somewhere, picking something up, tasting something, checking out the condition of fruit or dough that was resting, or checking on something in the oven. She never wasted any time, and her curiosity kept her going. . . . The Zuni Café Cookbook is just like that—lots of movement—and every bit of information is important.”

Judy’s passion for detail extends to the realm of ingredients. She possessed an innate understanding of the art of selection and an uncanny knack for articulating it, something I witnessed when I met her at an olive oil tasting in 2011 and that I would go on to read in her book. For instance, her wisdom on ripe figs: “If you look for pretty, you may miss the best ones. . . . Shrunken and wrinkled is actually good, as long as it is heavy,” she says in her headnote for chicken braised with figs, honey, and vinegar (page 350).

In a moment when everyone from pop music producers and actors to suburban moms and viral TikTok creators feel compelled to write a cookbook based on aesthetics, I think of the romantic yet informative way Judy writes about ugly-delicious figs. As the culinary world swirls, Judy’s work stands as a beacon for enduring greatness.

Even the cookbook’s quiet, unfussy elegance feels unique to Judy and to it. Part of that is Judy’s culinary philosophy, which I suspect she helped to make mainstream: ingredients should be the uncomplicated main character. “The process of deciding what to cook should always begin with where to shop and what to buy. . . . Only then should you settle on the preparation, which should suit the qualities of those ingredients, as well as your experience, time frame, and equipment,” she writes. The book can be sentimental at times in this way, but it never feels like an overshare, largely focusing on cooking as an archive of experience and craft.

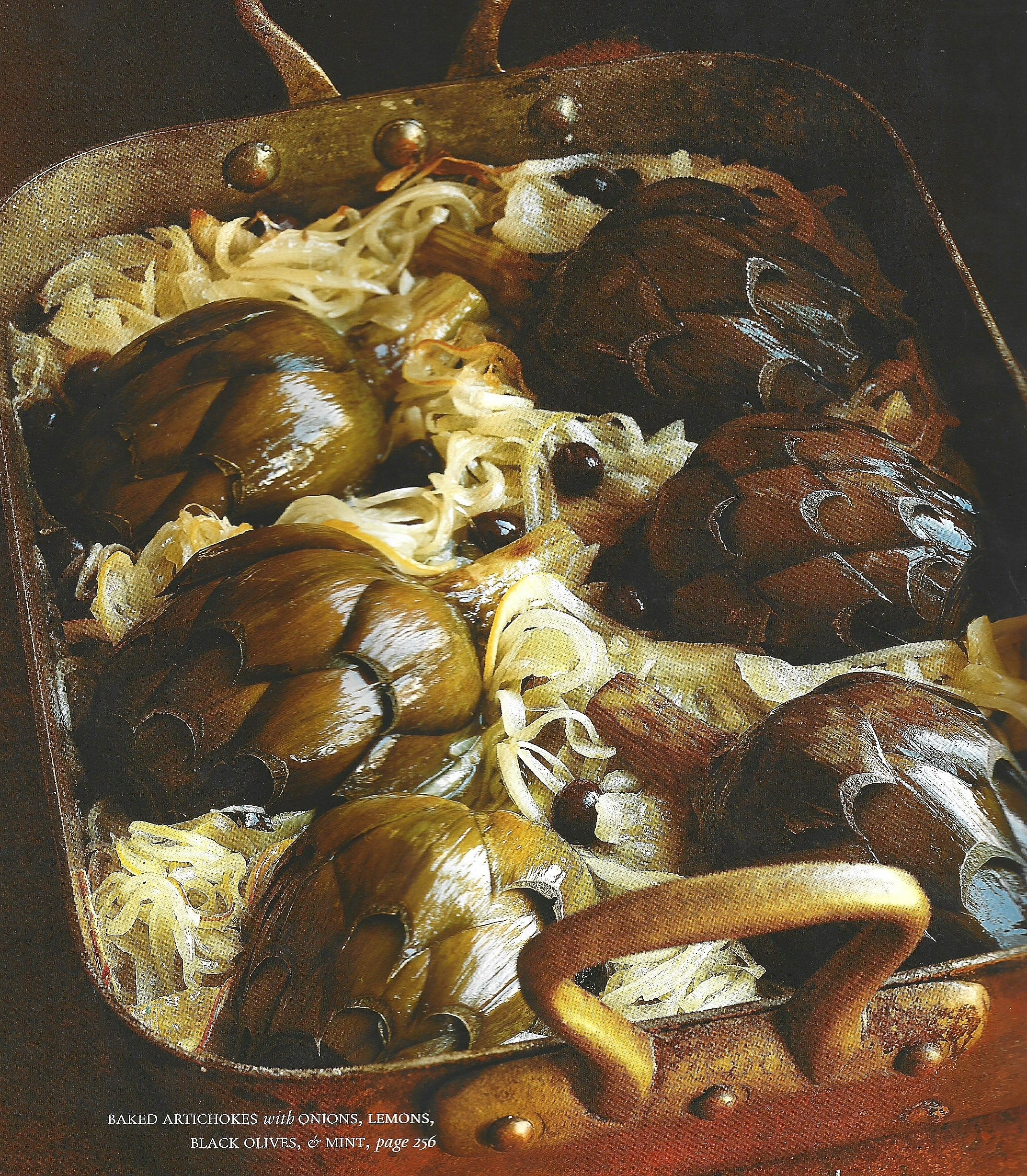

Even Judy’s full 250-recipe selection isn’t advertised in the table of contents. There are hardly any photographs either. The cover of the book, with its perfect nectarines, prosciutto, and green almonds might lead you to believe that it could be a coffee table book, full of glossy, high-contrast, highly saturated photographs, but it’s not. This sets her cookbook apart from many contemporary food writers and their books. This approach is interesting to ponder, especially for me, since I’ve been thinking about writing a cookbook, and part of the process entails writing a proposal with a full list of super enticing, honey to a bee-like recipes. It feels like they need to have bangin’ titles—be clickbaity, or else. Plus, they all need to be photographed—and beautifully—and there should be a QR code that leads to a reel or a video or a soundtrack , right? That process can feel overwhelming, and the way Judy’s book, blessed with a publication date predating TikTok, stands out as a book that speaks for itself is really cool and comforting.

Beyond her lyrical guidance in choosing high-quality ingredients, The Zuni Café Cookbook features recipes that home cooks can use to hone their essential cooking techniques. This, I believe, is one reason why her cookbook is an indispensable resource—and why it has been praised by many, including Harold McGee, Anthony Bourdain, Nigella Lawson, Alice Waters, and Samin Nosrat. When the cookbook came out in 2002, the New York Times accurately predicted its success when it designated the book as “this year’s best cookbook—the one people are still likely to be talking about, and cooking from, 20 years down the line.” The book’s longevity stems from Judy’s willingness to share her wealth of information, which went far beyond the norm of many contemporary cookbooks of the era—and of today.

The trust she instills is achieved through sections that show the importance of what may seem obvious, but not widely understood like in the “The Art of Tasting” and “The Practice of Salting Early,” and the ins and outs of successfully roasting (offering five pages of insights beginning on page 391). There’s also her guide on preparing a “very modest, very manageable” mock porchetta on page 408—which, while not a vegetarian proxy (thankfully), is a much smaller, stuffed piece of pork roast that calls only for shoulder meat, not the traditional whole roast pig. There are explanations of how to transform stock into a “satiny, richly flavored sauce” on page 56 and of how to achieve the “most superficial cooking possible” in the blanching section on page 100. Then there’s probably the most comprehensive guide on preparing granita that I’ve read, with multiple variations, starting on page 460.

As I progressed through the kitchen and learned more and more stations, more and more dishes, becoming familiar with the restaurant structures and systems and my (mostly) dear coworkers, I soon realized that the book was everywhere. It was there in the way Juanito shucked the oysters and diced the shallots for the mignonette every day; it was in the way we made aioli to serve with the tower of shoestring potatoes; it was in the way I got a glimpse into Judy’s palate, tasting her protégé’s menus; it was in the glowing embers of the mesquite grill and in the margarita served up, shaken only with fresh lime juice, tequila, a splash of Cointreau, and superfine sugar.

By the time the COVID-19 pandemic hit the United States in March 2020, I had been writing the dinner and lunch menus for Zuni a few times a week. It was probably the most challenging and immediately rewarding job I had ever had. But I was about to be laid off, and almost everything I’d cherished about my time at Zuni was about to come to end. The tastings, the menu planning, cooking alongside my friends, shopping at the farmers’ market to find pristine asparagus: all of it came to feel unsafe.

As those COVID days I spent at home turned from weeks into months, I realized that my more than five years at Zuni were officially over. I needed to try my hand at something new, to pursue something unfamiliar—but not too unfamiliar. During my last couple years at Zuni, I had been studying journalism, which led me to start writing a cooking column for the San Francisco Chronicle.

It was that summer, though, while still confined and unnerved in my apartment on Folsom Street, that I sat down at my dining table and looked up at my collection of cookbooks. I plucked out my copy of The Zuni Café Cookbook, like I was turning to an old friend for comfort and solace. Suddenly hit with nostalgia, I found myself turning the pages, unable to resist the allure of the few beautiful photographs, Judy’s words, and the memories of making her food.

I decided to make a familiar bowl of soup and then tie up a seductive mock porchetta with garlic and orange zest to roast the following day. As it marinated, I had some time to go where I usually went during the pandemic when I just needed to get out: the farmers’ market. I found bright red Albion strawberries and decided to make a granita. I told myself that it would be “refreshing, elegant, and charming,” as Judy calls granita—and it was.