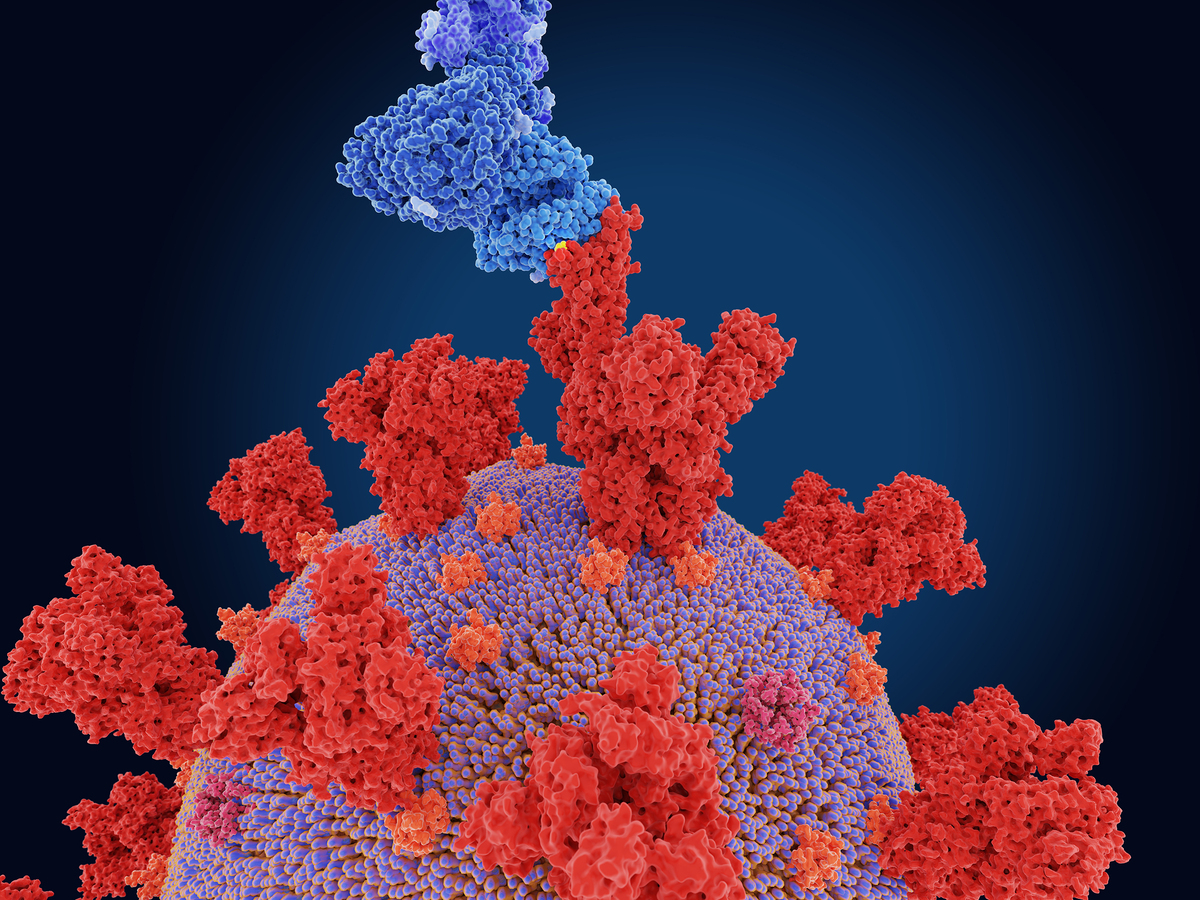

The coronavirus variant first spotted in South Africa alarms scientists because it evolved a mutation, known as E484K, that appears to make it better at evading antibodies produced by the immune system.

Juan Gaertner/Science Source

hide caption

toggle caption

Juan Gaertner/Science Source

The coronavirus variant first spotted in South Africa alarms scientists because it evolved a mutation, known as E484K, that appears to make it better at evading antibodies produced by the immune system.

Juan Gaertner/Science Source

Concern about new coronavirus variants has grown quickly in recent months.

First, scientists in the United Kingdom spotted a more contagious coronavirus strain that spread like wildfire through the London area. Then, researchers in South Africa spotted one that appears to evade the immune system. Next, another variant was flagged in Brazil because it looked like it could infect people who had already been infected once before.

And now there has been a flurry of reports about homegrown variants in the United States. What’s going on? How worried do we really need to be about them?

The short answer is, worried but probably not panicked. The virus is doing what viruses do: evolving to find new ways to continue to infect people.

“It’s infected millions of humans around the world now, and it’s probably just getting into a more intimate relationship with our species,” says Jeremy Kamil of Louisiana State University, who spotted a mutation that the virus appears to have evolved repeatedly in different parts of the United States.

The fear is that just as humanity appears to be finally turning the corner in the battle against the virus, the variants could give the pathogen the upper hand once again. They could trigger a new surge. And new, even more worrisome variants could emerge because the virus is still spreading so widely.

“They’re definitely something that we need to be paying attention to and designing our pandemic response around,” says Trevor Bedford, a computational biologist at the Fred Hutchinson Cancer Research Center in Seattle. “I don’t think the sky is falling, but I think it’s something that absolutely bears attention.”

Viruses mutate all the time. Most of the time, those mutations don’t pose a threat. But the current crop of coronavirus mutations has made the virus more contagious and may have made the virus more likely to make people seriously sick. It appears the mutations may also make it more likely people could get reinfected and make the vaccines less effective.

But we’re fighting back: The vaccines are rolling out, and so far it looks like they work against the variants to protect people from getting very sick or dying. If enough people in the U.S. can get vaccinated fast enough while also keeping up safe behaviors, this could prevent another major surge of cases and deaths. It could also help prevent new, dangerous variants from evolving because the more the virus spreads, the greater chance it has to mutate.

Here’s a primer on the variants that scientists are watching most closely:

Variant B.1.1.7: first spotted in the U.K.

This variant is still the strain that public health experts in the U.S. are most concerned about. That’s because it clearly is far more contagious than the original strain — perhaps 50% more infectious. This variant also looks like it may make people sicker.

And it appears to be already fairly widespread in the United States. At least 2,500 cases have been confirmed in at least 46 states, according to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Its real prevalence, like that of other variants, is assumed to be far more widespread. The U.S. isn’t sequencing the DNA of enough virus samples to know exactly how much more prevalent. But the CDC has predicted it will become the dominant strain throughout the U.S. later this month.

Variant B.1.351: first spotted in South Africa

Scientists are also alarmed by this variant because it evolved a mutation that appears to make it stealthier. That mutation is known as E484K (sometimes pronounced “eek”), and it appears to make the virus better at evading antibodies produced by the immune system. That means some drugs don’t work against this variant.

It also might be able to infect people who have already recovered from the virus. And, most concerning, laboratory studies suggest the vaccines may be less effective against it. This variant has been confirmed at least 65 times in at least 17 U.S. states, according to the CDC.

Variant P.1: first spotted in Brazil

This strain, frequently called P.1, also has the E484K mutation. It set off alarms because it swept through the Amazonian city of Manaus, which had already been ravaged by the virus. That indicated it could evade the body’s natural defenses and reinfect people. It has been spotted at least 10 times in at least five U.S. states so far.

But wait, there’s more: emerging U.S. variants

More recently, scientists have started identifying homegrown variants in the U.S. that have raised red flags. Two have gotten the most attention:

1) A variant that has been spreading quickly in California, B.1.427, appears to be more contagious than the original strain but not as contagious as the variant first spotted in the United Kingdom. While researchers at the University of California, San Francisco, reported some evidence that it may make people sicker, that finding remains weak so far.

2) Another variant appears to have started spreading quickly in New York City in January. Called B.1.526, it’s concerning because it has that stealthy E484K mutation. While some researchers think it may be more of a concern than the variant spotted in California, it remains unclear whether it is more contagious and how much of a threat it may pose. But it has been spotted elsewhere in the Northeast.

“It’s something we should keep an eye on and make sure that we continue to monitor the situation,” says Kristian Andersen, a scientist at the Scripps Research Institute. But that doesn’t mean it will turn out to be a serious problem, he adds.

“There’s a lot of things we need to keep eyes on, and then we keep our eyes on it, and then it turns out to not be important. In fact, the vast majority of situations [are] exactly that.”

But, Andersen adds: “We do have these other variants that we need to keep absolute focus on because we know they are of concern.”