Naeblys/Getty Images

You wouldn’t know it by looking at any one of us, but coursing through our veins every second of every day are tiny variations that categorize our blood into groups: A+, A-, B+, B-, O-, O+, AB+ and AB-.

These minute differences usually don’t matter until they matter — when you’re in the hospital in need of a blood transfusion, or after you’ve donated blood, and you learn which type you have. Some people find out during pregnancy, when special treatment is required for someone with a negative blood type.

But ongoing research into blood type suggests it may matter more than we think it does — at least when assessing risk for certain health conditions, especially heart disease. These invisible differences in the blood may give some people an edge at staving off cardiovascular problems, and may leave others more susceptible.

What does blood type mean, and how are they different?

The letters A, B and O represent various forms of the ABO gene, which program our blood cells differently to form the different blood groups. If you have type AB blood, for example, your body is programmed to produce A and B antigens on red blood cells. A person with type O blood doesn’t produce any antigens.

Blood is said to be “positive” or “negative” based on whether there are proteins on the red blood cells. If your blood has proteins, you’re Rh positive.

Ekachai Lohacamonchai/EyeEm/Getty Images

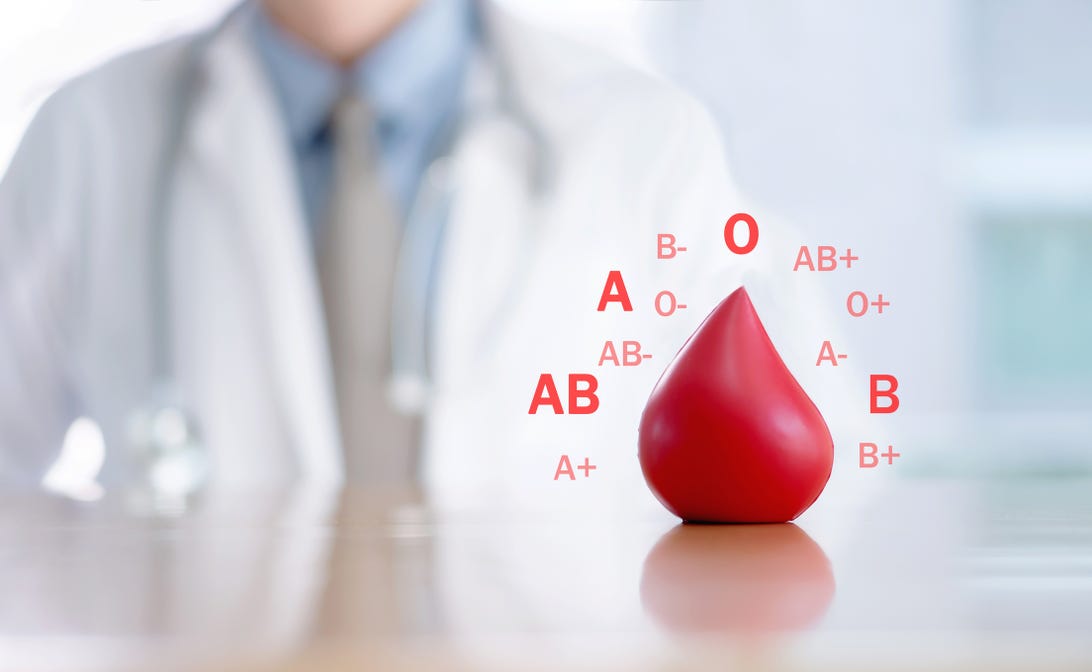

People with type O- blood are considered “universal donors” because their blood doesn’t have any antigens or proteins, meaning anybody’s body will be able to accept it in an emergency.

But why are there different blood types? Researchers don’t fully know, but factors such as where someone’s ancestors are from and past infections which spurred protective mutations in the blood may have contributed to the diversity, according to Dr. Douglas Guggenheim, a hematologist with Penn Medicine. People with type O blood may get sicker with cholera, for example, while people with type A or B blood may be more likely to experience blood clotting issues. While our blood can’t keep up with the different biological or viral threats going around in real time, it may reflect what’s happened in the past.

“In short, it’s almost like the body has evolved around its environment in order to protect it as best as possible,” Guggenheim says.

The blood types most at-risk for heart disease

Arctic-Images/Getty Images

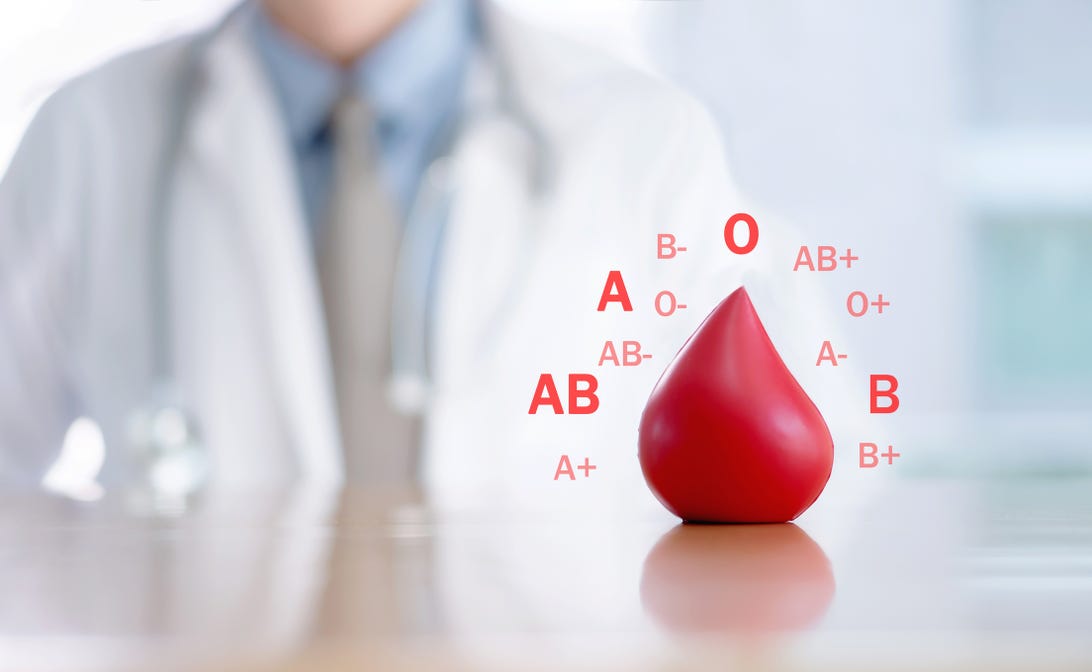

People with type A, type B or type AB blood are more likely than people with type O to have a heart attack or experience heart failure, according to the American Heart Association.

While the increased risk is small (types A or B had a combined 8% higher risk of heart attack and 10% increased risk of heart failure, according to one large study) the difference in blood clotting rates is much higher, per the AHA. People in the same study with type A and B blood were 51% more likely to develop deep vein thrombosis and 47% more likely to develop a pulmonary embolism, which are severe blood clotting disorders which can also increase the risk of heart failure.

A reason for this increased risk, according to Guggenheim, might have to do with inflammation that happens in the bodies of people with type A, type B or type AB blood. The proteins present in type A and type B blood may cause more “blockage” or “thickening” in the veins and arteries, leading to an increased risk of clotting and heart disease.

Guggenheim also thinks this may describe the anecdotal (but inconclusive) decrease in risk of severe COVID-19 disease in people with type O blood, which has inspired research. Severe COVID-19 disease often causes heart problems, blood clotting and other cardiovascular issues.

Peter Dazeley/Getty Images

Other consequences of blood type

People with type O blood enjoy a slightly lower risk of heart disease and blood clotting, but they may be more susceptible to hemorrhaging or bleeding disorders. This may be especially true after childbirth, according to a study on postpartum blood loss, which found an increased risk in women with type O blood.

People with type O blood may also fare worse after a traumatic injury due to increased blood loss, according to a study published in Critical Care.

Other research has found an increased risk for cognitive impairment in people with type AB blood when compared to people with type O. Cognitive impairment includes things like trouble remembering, focusing or making decisions.

Should I change my lifestyle based on my blood type?

While research available now shows that blood type can tip the scale in terms of someone’s risk of developing heart disease, big factors such as diet, exercise or even the level of pollution you’re exposed to in your community are also major players in determining heart health.

Guggenheim says that for patients trying to keep their heart healthy, there’s no special recommendation that he’d make other than a good heart healthy diet that lowers inflammation, regardless of someone’s blood type.

Lean proteins, healthy fats, fruits, vegetables and whole grains are all part of a heart-healthy diet.

Lina Darjan/500px/Getty Images

But, he notes, future research could offer more definitive ways doctors treat patients based on their blood type. All factors considered equally, a patient with healthy cholesterol levels and type A blood may benefit from taking aspirin each day whereas it might not be necessary for a person in the same boat with type O blood.

“A well-balanced, heart-healthy diet in general is going to be what any physician is going to recommend, and I would say that ABO doesn’t change that,” Guggenheim says.

“I don’t think there’s a protective benefit from just having type O blood that contributes to being scot free,” he adds.

The information contained in this article is for educational and informational purposes only and is not intended as health or medical advice. Always consult a physician or other qualified health provider regarding any questions you may have about a medical condition or health objectives.