BLACKSMITH FORK RIVER — When watershed scientist Janice Brahney and grad student Macy Gustavus go for a hike to take water samples, even in the most remote places, they’re always confident they’ll find what they’re looking for.

“Yeah, we find plastic in pretty much all of our water samples,” Gustavus said, “if not all of our water samples.”

Brahney used words like “alarming” and “shocking” as she described her ongoing research project. An associate professor at Utah State University, she’s looking for tiny particles of microplastics in the air we breathe and the water we drink.

“We’re finding plastics everywhere we look,” Brahney said, “which is really concerning.”

The problem stems from the fact that plastic is used in almost every aspect of modern-day life. We leave lots of plastic stuff lying around, and we dump millions of tons of it into the trash every day. All that plastic disintegrates over time, breaking down into tiny particles that go, well, pretty much all over the place. They find their way into our environment, becoming a component of blowing dust.

“Our own mismanagement of plastic waste is largely how it’s getting into the environment,” Brahney said.

In remote places like the headwaters of the Blacksmith Fork River, microplastics are in virtually every big gulp of water.

“Any given gallon of water,” Brahney said, “whether you take it from within a river in the city or high up in the mountain headwaters, it’s going to have plastics in it.”

Brahney and her students have also set up air-sampling stations on towers high in the mountains; their filters routinely collect particles of microplastics drifting with the wind.

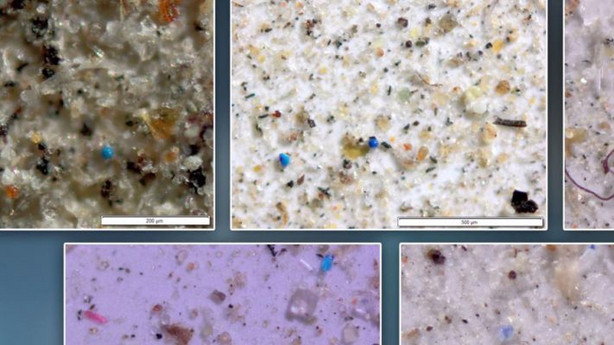

In her lab on the USU campus, Brahney examined a typical sample with a high-power microscope and instantly spotted what she was looking for.

“It’s green,” she said. “An unnatural green, so this is likely a piece of plastic.”

As she scanned the sample, she found other brightly colored bits, some red, some yellow, and a tiny blue chunk that looked entirely different from other dust components like minerals, smoke, and pollen.

“A fragment like this could have broken apart off many different blue-colored plastic items that we use in our everyday life,” Brahney said.

She used a digital measuring system in the microscope to estimate the size of the particle. It measured 38 microns in diameter.

“This is four times larger than a red blood cell,” Brahney said. In other words, incredibly tiny.

In the last year, Brahney has published two scientific papers in prestigious peer-reviewed journals, an indication that microplastics is a field of growing scientific interest. Her conclusion was that at any given time, more than 1,000 tons of plastic are swirling around in the sky above the western states. It’s landing everywhere, all the time.

As she took water samples from the Blacksmith Fork River, Gustavus said, “We have plastic that is coming from the sky right now and falling into the river.”

If all of this sounds like a good excuse to avoid the great outdoors, Brahney has some cold water to throw on that idea: the microplastics problem is likely even worse indoors.

“It’s more likely that you’re exposed to more atmospheric or environmental plastics inside,” Brahney said, but there’s little hope of getting away from it anywhere. “The reality now is that you can go to the middle of the Grand Canyon and think that you’re breathing clean fresh air. But in fact, you are also breathing microplastics there.”

Brahney has been studying the particles, partly to figure out how they wind up in remote places. Most of the disintegrating plastic is in urban areas, she said, but surprisingly, it’s mostly in rural areas that it goes high into the sky. It spreads along highways where speeding cars and trucks launch it skyward at high velocity.

“What we found,” Brahney said, “is that highways are largely responsible for moving plastics high into the atmosphere.”

It climbs skyward almost as high as the jet stream where winds carry the particles at high speeds, spreading them around the world in a few days. There are always particles up there, Brahney learned, and they are always falling to the ground.

“So we are constantly ingesting microplastics in our food and drinking water,” Gustavus said.

“Definitely I think people should be alarmed,” Brahney said. “There’s virtually no place on the surface of the Earth that you can go that isn’t going to be contaminated with plastic garbage. I think that’s very upsetting.”

The science of microplastics is new enough that it’s hard to know how important it is. No one knows if breathing or drinking the tiny particles is any more unhealthy than all the regular stuff that floats around the earth.

“We don’t truly know what the consequences are,” Brahney said.

The science is a work in progress. So, too, is the plastic pollution. It continues all the time, Brahney said, all over the Earth.

“We’re almost arriving at this understanding a little bit late since we don’t yet know what the consequences are,” Brahney said. “But we’re already at this state where the plastic pollution is quite intense and quite concentrated in really remote locations.”

×