The adrenaline rush begins with an Instagram notification: Press SF just posted a photo. Instantly, I unlock my phone, racing to assess what jewel just hit the feed. Maybe it’s an image of a crouching crab, lovingly carved from a cucumber and immortalized in the 1996 edition of How to Garnish. Or a recipe for “Imprisoned Eggs for Timothy Leary,” which pairs bacon, sugared strawberries, and fried eggs “like a Utopian community” as instructed by the California Artists Cookbook in 1982.

I didn’t know I wanted any of these cookbooks, much less that I’d feel a desire so strong it would cause me to interrupt whatever I’m doing (slicing onions, writing this very article) to be the first to click the “buy” link. This is what it takes to secure the bag—a first edition of Martha Stewart Entertaining or a lovingly worn copy of Parsons Bread Book—in the online trenches of competitive vintage cookbook collecting.

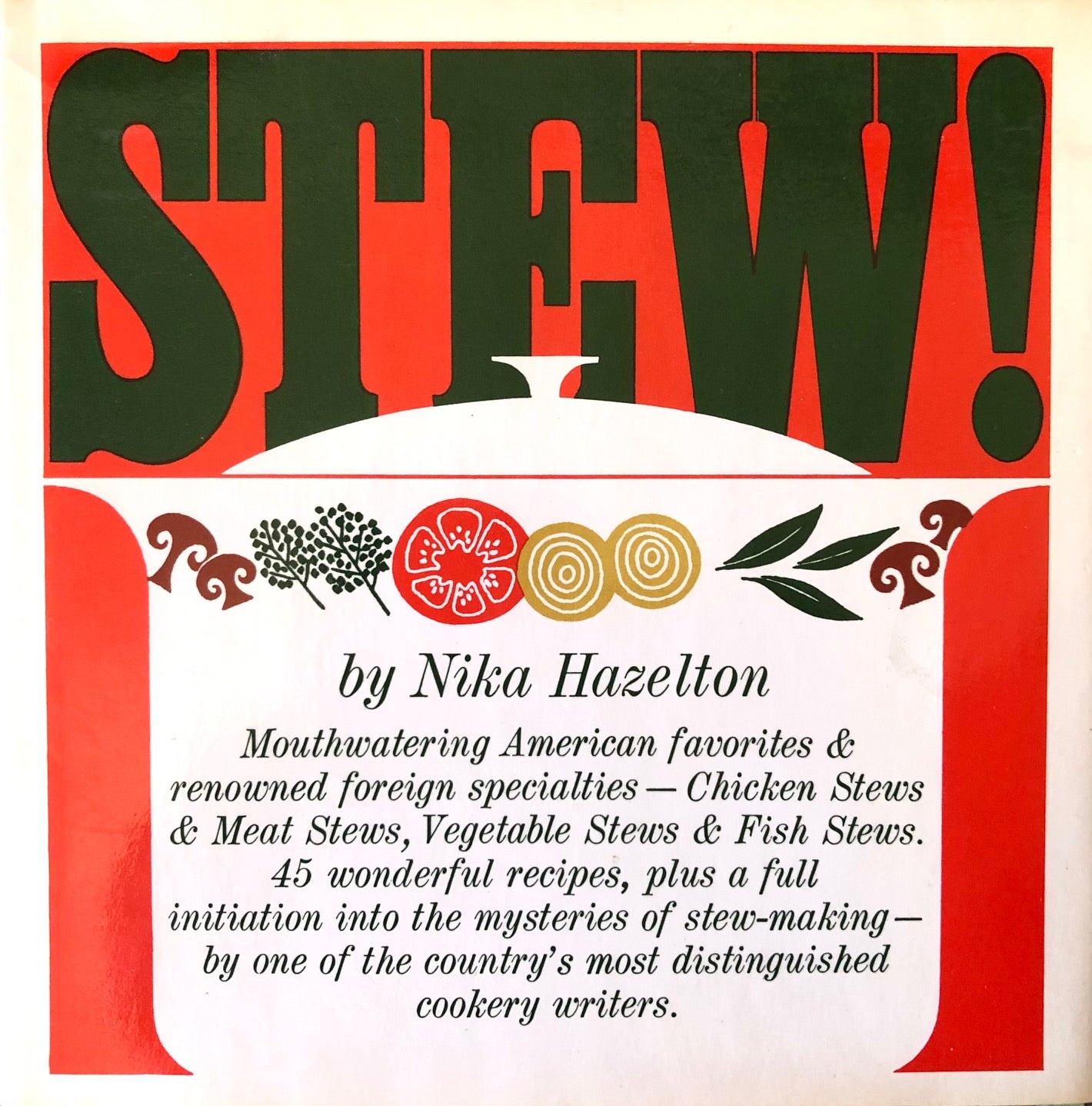

In decades past, antiquarian cookbook collectors eager to own a few pages of the culinary past have flocked to rare bookstores, estate sales, and even auction houses. Today, a new generation is discovering the appeal of vintage cookbooks—the nostalgic, sometimes cringy recipes! the refreshingly terrazzo-free photo shoots!—and the thrill of the hunt online.

“There are a lot of polished and chic cookbooks out now, but there’s something special about picking up a 1980s cake decoration cookbook with a different sensibility,” says Paulina Nassar, cofounder of Press, the most adrenaline-inducing cookbook selling account I follow. “I have nothing against new cookbooks—the recipes are everything that people respond to now. But a vintage cookbook is like taking a side road.”

Nassar and her husband, Nick Sarno, opened Press SF in 2010, with a brick-and-mortar store in San Francisco’s Mission District. The shelves were piled high with books on photography, crafting, and cooking—anything with images. A following grew. A few years later, the couple’s interest in all things handmade led them to launch West Coast Craft in 2013, a popular design and craft fair that brought together artisans and the kind of avid customers usually relegated to online shopping like Etsy.

By 2017, the growing appeal of West Coast Craft and the time-intensive nature of selling vintage books prompted the couple to close the physical location and move the bookstore fully online. Nassar had already been using the shop’s growing Instagram following to promote books that were available for in-store purchase, so she decided to begin using social media to publicize the launch of online ordering. It was a huge hit.

“Vintage food and drink books are such a great way to connect with people over social media, because there’s always something to say about them,” agrees Celia Sack, owner of the cookbook store Omnivore Books. “Sometimes they’re funny and dated, or erotic, or important.”

Sack began using Instagram and Twitter to promote Omnivore’s rich collection soon after their doors opened in San Francisco in 2008. Followers flipped for rare copies, like a signed first edition of Chez Panisse Café Cookbook from hometown hero Alice Waters, as well as books focused on skills like pickling seasonal produce or Japanese kaiseki that were underrepresented in the modern market.

For vintage cookbook sellers, social media isn’t just a mechanism to move product for a meaningful return. For starters, the quantities are limited. “People sometimes are like, ‘Do you even sell these?’ We do, but we generally have less than five copies of each book and more than a hundred thousand people potentially looking at it,” says Nassar.

Today, Nassar says that most books she posts on Instagram sell in under three minutes. She aims to sell multiple copies of the same rare book—say, The Four Seasons Cookbook or The Wicca Cookbook—amassing copies at places like library sales and eBay until there are at least a handful ready to sell. But amassing enough supply to meet demand is no easy feat. Nassar says she’s seen an increase in interest over time, potentially attributed to heightened enthusiasm for baking, cooking, and other domestic activities in light of the pandemic.

At the same time, some of the most prized titles have never been produced in mass quantities. Parsons Bread Book, a 1974 release featuring recipes from students and staff at the prestigious design school, has topped Nassar’s holy grail list for years—and she spotted her first-ever copy in the wilds of a half-price book sale in Texas just a few months ago. “I was shaking, I was so excited,” she says with a laugh.

“Sometimes they’re funny and dated, or erotic, or important.”

By dropping new cookbook stock on social media, sellers aim to spark that same sense of surprise and delight. It’s a form of community building that incentivizes customers to come into physical locations or click around the website for a gem that hasn’t been posted to the masses. If Instagram comments are any indication, the gap between demand and supply is a source of (mostly) good-natured frustration—and, like trying to buy a Telfar bag, the thrill of the hunt is getting a new generation interested in collecting vintage cookbooks beyond their favorite accounts. Sellers like Nassar often encourage out-of-luck buyers to search for extra copies on eBay, even giving out ISBN reference numbers to ease the process. “We want to encourage people to go and find these books and look at these used booksellers a little closer,” she says. “Books don’t just have value if they’re a first-edition Dickins.”

Claire Bubeck, a multimedia artist and pre-K teacher in Columbus, Ohio, has bought more than 17 vintage books secondhand from sellers on eBay or Amazon that she discovered on Press’s Instagram account and a few other collector pages like The Thing Is and Mast Books. This is partly because her work keeps her off her phone during the weekday, when many of the books are posted, and also because the competition is just that stiff. Her gateway cookbook was Variety Meats, a gristly 1982 guide to preparing animal organs, tails, and sweetbreads. It was love at first click.

“I think the way old recipes are phrased and food photographs used to be taken is so uncanny valley and weird,” says Bubeck. A visual artist who often uses vintage books as a medium for collage, she’s never cooked a recipe from her collection, which varies from The Cooking of Italy (1968) to art books like Let There Be Neon (1979). After a year of following post notifications only to encounter a dead link by the time she checked her phone, she snagged a copy of Sushi for Parties, a guide to creating trippy Technicolor maki and nigiri published by Ken Kawasumi in 1995. The step-by-step instructions for creating adorable panda faces from cod roe and sushi rice are rife with aesthetic inspiration, if not temptation, to take to the kitchen. “The pomegranate-shaped sushi looked super smack to me,” she says, “but I’m too lazy to make that.”