“Vaccination and boosters are key to preventing further transmission of COVID-19 and help prevent new variants like omicron from emerging,” said Dr. Kathleen E. Toomey, commissioner of the Georgia DPH.

The highly mutated COVID-19 variant was named omicron by public health authorities who say it’s likely omicron had been circulating for some time before it was identified in South Africa Nov. 25. Scientists are scrambling to learn about omicron’s transmissibility, severity and ability to evade vaccines. AJC journalists are following the variant with a focus on what it means in Georgia.

Public health authorities say it’s likely that the variant had already been circulating for some time before it was identified in South Africa on Nov. 25. The WHO said as of Wednesday at least 23 countries had reported cases of omicron, and that they “expect that number to grow.”

“It’s certainly no surprise that omicron has been found in Atlanta — one of the most dynamic and international cities in the world. Now that omicron is here, along with delta, it’s even more important than ever to do what we know will slow further transmission,” said Dr. Michael Eriksen, founding dean of Georgia State University’s School of Public Health. “Specifically, get fully vaccinated, and if you’re eligible, get boosted. It’s also important to get tested frequently so that if you test positive, you can isolate and help stop the spread.”

Scientists are scrambling to learn about omicron’s transmissibility, severity and ability to evade vaccines. Even if existing vaccines are found to be less effective against the variant, public health experts say vaccination and boosters could provide enough of an antibody defense to stave off severe illness and death.

In the days leading up to the state’s first case, Georgia’s DPH and private testing companies searched for the variant using genomic sequencing, a process of finding small changes in the virus’ genetic code. The process is used worldwide to identify emerging variants, but the U.S. has lagged other nations in using it.

Founded in 2008 to promote the international sharing of data on influenza infections, the GISAID database is now tracking the evolution of the coronavirus.

GISAID, a non-profit which was launched in 2008 with the support the U.S. government and in partnership with the CDC, provides a global database of genomic sequencing of coronavirus samples. Since the first whole-genome sequences were made available through GISAID on Jan. 10, 2020, nearly 6 million genomes of the pandemic coronavirus from 204 countries and territories have been made publicly available through GISAID.

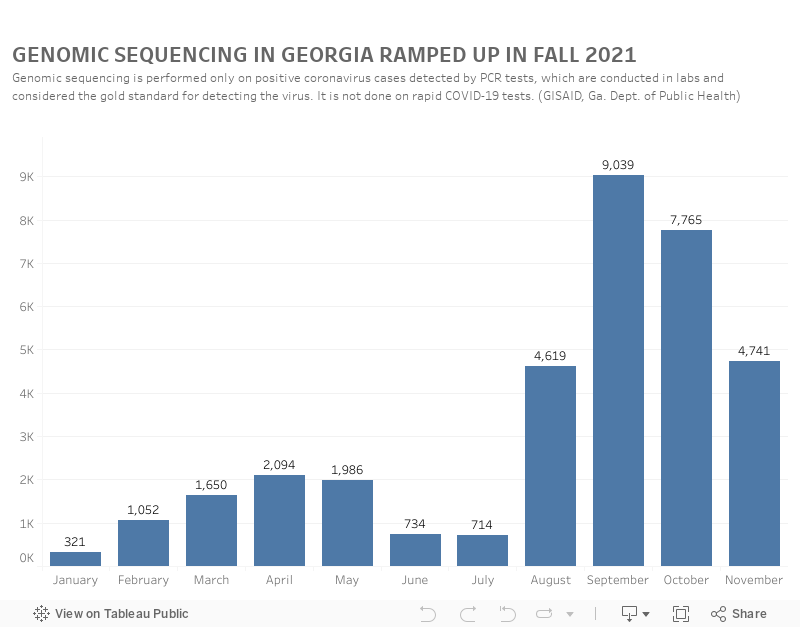

Across the country, including Georgia, the number of sequences performed has dramatically increased since January, according to GISAID, a tracking initiative that provides a global database of genomic sequencing of coronavirus samples.

In Georgia, the number of sequences performed has dramatically increased over the year from a few hundred in January to over 7,500 in October, and 4,741 in November, according to GISAID, a tracking initiative that provides a global database of genomic sequencing of coronavirus samples.

Genomic sequencing is a complex process done on a small percentage of positive coronavirus samples. The process begins with extracting the genetic material from a positive sample taken from a COVID-19 patient. Then, sequencing machines map out the entire SARS-CoV-2 virus genetic code. The machine can take as many as three days to complete that step, and then scientists must manually review the findings.

Most samples of confirmed coronavirus tests, however, do not get sequenced.