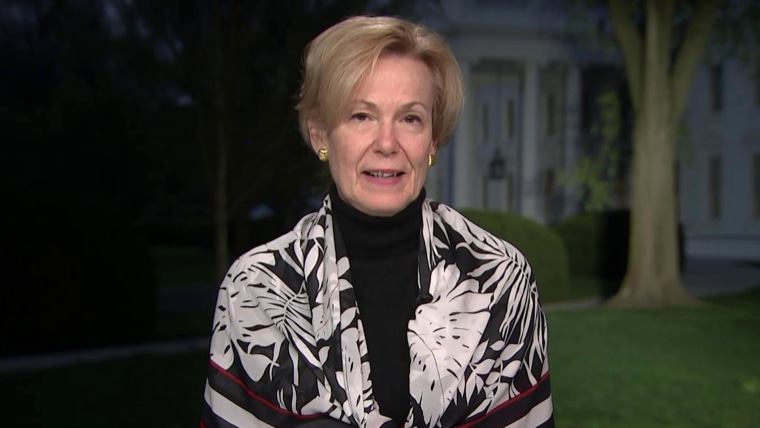

In the predawn hours of March 30, Dr. Deborah Birx stepped in front of the camera on the White House lawn and made an alarming prediction about the coronavirus, which had, by then, killed fewer than 3,000 people in the United States.

“If we do things together, well, almost perfectly, we can get in the range of 100,000 to 200,000 fatalities,” Birx, coordinator of the White House coronavirus task force, told Savannah Guthrie of NBC News’ “Today” show.

Full coverage of the coronavirus outbreak

“We don’t even want to see that,” she added, before Guthrie cut her off.

“I know, but you kind of take my breath away with that,” Guthrie said. “Because what I hear you saying is that’s sort of the best-case scenario.”

“The best-case scenario,” Birx replied, “would be 100 percent of Americans doing precisely what is required.”

On Saturday, Birx’s prediction came true, as the number of lives lost to Covid-19 in the U.S. topped 200,000.

Experts like Dr. Tom Frieden, former director of the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, said it didn’t have to be this way.

“Tens of thousands of people would not have died if the U.S. response had been more effective,” said Frieden, now president of Resolve to Save Lives, a global public health initiative.

Michael Osterholm, director of the Center for Infectious Disease Research and Policy at the University of Minnesota, said Birx’s prediction in late March was “very sobering.” That was the time, he said, to develop and implement a plan to stop or at least slow the spread of the virus.

That didn’t happen then, and it hasn’t happened since. “Where is our national plan?” Osterholm asked. “How are we this far along and we don’t have one?”

“We have a long way to go,” he added.

Indeed, the country still faces many challenges in overcoming the pandemic, including agreeing on even the most basic facts. Americans are still fighting over whether to wear masks, whether the virus is serious and to what extent it’s safe to reopen certain businesses and to resume certain activities.

In short, 100 percent of Americans — government officials included — still aren’t doing precisely what is required.

Another ominous prediction

Now, many experts are making another ominous prediction: A surge in the number of new infections in the fall and winter, combined with growing fatigue over social distancing and other public health measures, could result in more than 415,000 deaths in the U.S. by January, according to the Institute for Health Metrics and Evaluation, or IHME, at the University of Washington.

The prediction comes even as doctors are growing more adept at treating patients and clinical trials are finding that treatments like remdesivir and dexamethasone can help. And as the pandemic has spread, it has moved into younger, healthier populations, who are less likely to die from Covid-19.

The IHME’s projections are by no means set in stone. Changes in human behavior, such as increased adherence to wearing masks, can bring the number down considerably, said the director of the IHME, Dr. Christopher Murray, a professor of health metrics sciences at the University of Washington. But the experiences of other countries have shown that, as the pandemic wears on, public complacency is a real concern.

“We’re seeing it in a very big way in parts of Europe, for example, where lack of vigilance is leading already to a big uptick,” Murray said.

The IHME model is one of several that the CDC uses to track the evolution of the pandemic, but it has faced its share of skepticism. The model often includes high degrees of uncertainty, and it was criticized early on for underestimating the number of deaths nationwide. In April, for example, the IHME model projected that the death toll in the U.S. through August could be 60,415, although the prediction included a wide range to account for uncertainties early in the pandemic.

It’s sort of like a train wreck that we know is unfolding and people keep grasping for some idea that it’s not that bad.

Murray said that the model is constantly being refined to provide more accurate scenarios but that most researchers in the modeling community had been warning for months that the pandemic could have a serious death toll. It’s the type of insight, Murray said, that makes the 200,000-death milestone all the more frustrating.

“There is obviously something pretty depressing about the whole drama as it unfolds,” he said. “It’s sort of like a train wreck that we know is unfolding and people keep grasping for some idea that it’s not that bad.”

200,000 who didn’t expect to die

For those whose loved ones have died, such complacency is “like a daily kick in the teeth.”

Nicole Hutcherson, of Goodlettsville, Tennessee, lost her father, Frank M. Carter, 82, to Covid-19 in April. Hutcherson said that since then, people around her have questioned whether the pandemic is real (it is) or have suggested that her father was already frail or sick before he became infected with the virus (he wasn’t).

“My dad could outwork most any 30-year-old,” Hutcherson said. “People are just not grasping that this is a big deal.”

Dr. E. Wesley Ely, a professor of medicine and critical care at Vanderbilt University Medical Center in Nashville, Tennessee, called the 200,000 deaths a “benchmark of sadness.”

“This is 200,000 people who didn’t think they were going to die this year,” Ely said.

Covid-19 has killed people of all ages, all races and all political affiliations. They include a veteran emergency medical technician with the New York Fire Department. A pastor in Texas. A nurse in South Carolina. Children who have succumbed to a rare inflammatory complication of the disease called MIS-C.

States currently logging the biggest numbers of daily Covid-19 deaths are California, Florida and Texas. By far, the state with the most deaths total is New York, with just over 33,900 as of Saturday.

A Covid-19 ‘tsunami’

Dr. Hugh Cassiere felt he was facing a “tsunami” of gravely ill Covid-19 patients when New York was at its peak of cases in March and April. He led a Covid-19 intensive care unit at North Shore University Hospital, part of Northwell Health, on Long Island.

The coronavirus presented new challenges even for veteran ICU physicians.

“There were a multitude of deaths every single day no matter the best that you could possibly do,” Cassiere said. “It was overwhelming professionally and emotionally.”

But not all patients made it to the ICU.

Joyce Brown Wigfall, a labor and delivery nurse in Forest Hills, New York, started feeling sick on March 30 — the day Birx mentioned 200,000 deaths.

Wigfall, 67, felt weak and had trouble catching her breath walking up stairs — unusual symptoms for a woman who raised five sons, loved Zumba exercise classes and had just completed a master’s degree in nursing with an emphasis in leadership, and had begun to pursue a doctorate.

“I was so proud of her,” said Wigfall’s son, Erik Brown, 33.

Within a week of falling ill, Wigfall was diagnosed with Covid-19, but she felt well enough to recover at home. Brown said his mother remained engaged with her co-workers from afar, and on April 12, said she was ready to go back to work.

On April 13, Wigfall’s health deteriorated rapidly. She died within hours. Her passing left an immeasurable void.

“She was the center of the family. She was the rock,” Brown said.

“I’m angry at the fact that we still don’t have any sort of concrete plan to get the country back to ‘normal,’ whatever that is,” Brown said. “There is still no way that we can go back to the life that I had prior to March 30.”

An unpredictable path

Much remains unknown about how the virus could progress in the fall and winter, particularly with regard to whether the changing seasons will affect how it spreads within communities, as cold weather draws people indoors. But experts stressed that maintaining vigilance will be one of the most effective ways to contain it and prevent runaway outbreaks.

A storm will do what it’s supposed to do. You can’t do anything about it. With an epidemic, we can change the trajectory.

A team at Northeastern University in Boston created a model that provides state and nationwide projections for up to four weeks in the future — akin to a weather forecast. Beyond four weeks, too many unknown factors can dilute the model’s accuracy, said Alessandro Vespignani, director of Northeastern’s Network Science Institute.

Numbers aside, Vespignani was adamant that certain proven strategies, when followed, would reduce the number of future cases and deaths.

Download the NBC News app for full coverage of the coronavirus outbreak

“A storm will do what it’s supposed to do. You can’t do anything about it,” Vespignani said. “With an epidemic, we can change the trajectory.”

Many of the ways to do that aren’t new, including wearing masks, practicing good hygiene by washing hands frequently and getting a flu shot, he said.

Managing the factors that can be controlled will be crucial in the months ahead, especially because most scientists are anticipating a new wave of infections in the fall and winter, coinciding with flu season.

“There’s winter coming, and there might be another wave of transmission ahead, so we still need to have a plan to deal with that,” said Sen Pei, an associate research scientist at Columbia University, who has done extensive Covid-19 modeling work. “Otherwise, we will still see people dying.”

The IHME model’s prediction that the U.S. will double its number of Covid-19 deaths by January, to 415,000, is not unrealistic, experts said.

Cassiere, of Northwell Health, said, “I think we’re going to easily hit 400,000.”