After autumn’s glorious red-gold foliage has turned brown and fallen to the ground, and after Halloween bags have been filled and emptied, we approach another American microseason, now that it’s November. It is time for the annual Pie Panic.

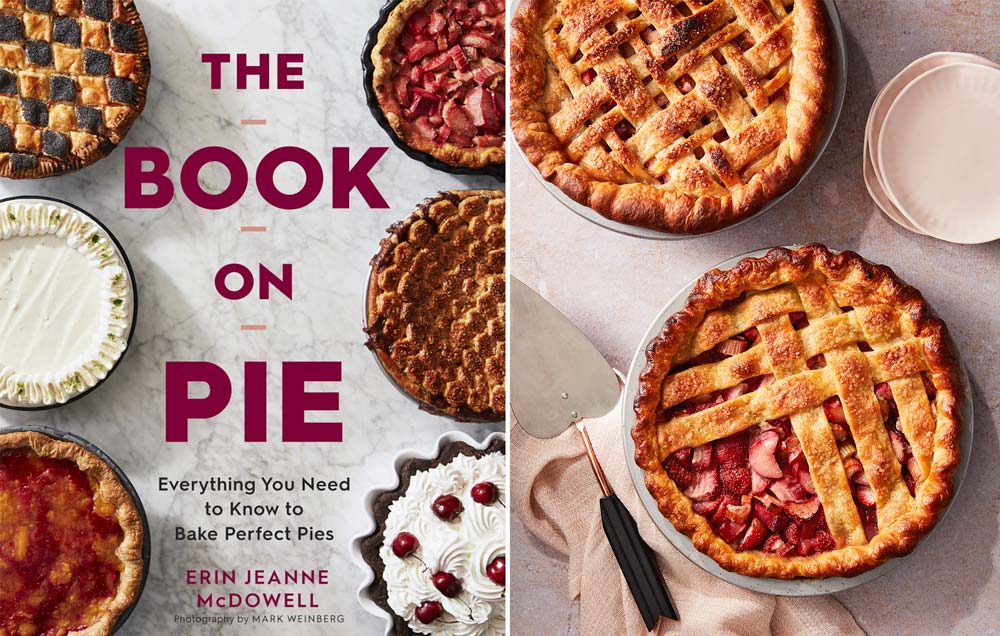

For all its down-home charm and soft patriotism, pie induces a swelling of fearful anxiety, particularly during the mad-dash rush of Thanksgiving. Cake, a pastry-loving friend once pronounced to me in one of those low-stakes quibbles about the supremacy of cake versus pie, is always good even when it’s bad, whereas pie, particularly with its finicky double crust, is more difficult to pull off. Recipe developers know this well. “During the week of Thanksgiving, my brother calls my Instagram DMs a 24-hour pie hotline,” Erin Jeanne McDowell, author of The Book on Pie, tells me. “People are coming to me to ask all these questions, and they’re all freaking out.”

Recipes for pie crusts can be deceptively short. Just flour, fat, salt, and cold water; cut them together; and roll out the dough—what can possibly go wrong? A whole lot, of course. Pie, as a dessert form, is the happy medium of two opposing forces—the crust underneath must be flaky and sturdy enough to hold together (but not so strong that it’s tough), while the filling sitting on top of it must be wet (but not so liquid that it makes the crust soggy). It is a feat of construction, delicately balancing wet and dry, tenderness and structure. And the crust is the foundation of it all.

At the heart of most pastry problems—and therefore of most Pie Panic—is the flour: its protein, when combined with liquid and kneaded or mixed, creates a network of strands of gluten that forms the crust’s structure. “You need gluten formation in pies, but you don’t need that much,” says molecular biologist and recipe developer Nik Sharma, whose latest cookbook is The Flavor Equation. The gluten structure helps the crust hang together, but excess gluten can make the crust’s internal structure too strong and tough.

For all its down-home charm and soft patriotism, pie induces a swelling of fearful anxiety, particularly during the mad-dash rush of Thanksgiving.

“Flour is the most critical part of the whole thing,” Rose Levy Beranbaum, author of nine cookbooks, including The Pie and Pastry Bible, tells me over the phone. One of the major issues is that standard recipes don’t tell you how they measure flour, and the variable methods of measuring (dipping and sweeping versus spooning and leveling versus sifting) can yield drastically different results. Accurate measurements are key, says Beranbaum, stating the obvious—but in truth, it’s an “obvious” that is often ignored. “It really matters with flour, because the difference can be three quarters of a cup. And that’s what really kills me. It’s a common-denominator failure.”

Also, unlike sugar, the chemical composition of flours is not uniform. Frustratingly, the protein content of different brands in the most commonly used flour, all-purpose, ranges from 7 to 12 percent—a gap that’s yawning enough to make a major difference. To eliminate some of the variability, Beranbaum specifies weight in her instructions—a pastry-professional practice that used to be considered too fussy for home cooks but is now becoming standard. And instead of all-purpose, she calls for pastry flour, which has a tighter range of 7 to 8 percent protein across different brands. She also adds cream cheese for tenderness and flavor.

Most recipe developers, however, don’t want to ask readers to buy a bag of less commonly used (and harder to find) pastry flour, so they stick to all-purpose. But then they must contend with that variation in the starch-protein ratio of different brands, which is where many issues begin. On the higher end of the spectrum of protein content is King Arthur Flour, which is made with all hard red wheat, with 11.7 percent protein, and on the lower end is White Lily Flour, which is made with all soft white wheat, with just 8 percent. In the middle are Gold Medal Flour, made with a mix of red and white wheats, with 10 to 11 percent protein, and Pillsbury, which has about 10.5 percent protein. More protein in the flour will absorb more water, which is why many recipes give a range for added water—“hydration” in technical pie-speak—instead of an exact flour-to-water ratio. Deciding how much water to add requires knowing what the dough should look like at that stage—a determination that may not be obvious to infrequent pie makers.

To solve some of that guesswork, Serious Eats baking guru Stella Parks, author of BraveTart, calls for a specific brand of flour and an exact amount of water for her flaky pie crust recipe. She prefers Gold Medal’s blue label flour, or similar brands like Pillsbury and Immaculate Baking, which also have around 10 percent protein content, for its starch-to-protein ratio. “It has just the right balance of protein and starch to make a dough that’s sturdy and easy to handle, but bakes up flaky, tender, and light,” she writes. Still, that’s no industry standard. Beranbaum and Sharma both use King Arthur Flour, which helpfully publishes the protein content on the side of their bags.

Any good pie crust recipe is about controlling that gluten development. “The fat coats the proteins and prevents gluten formation,” Sharma says of Parks’s technique of using a higher ratio of butter and squashing it into large pieces (instead of pea-size ones). He explains a number of tweaks that will all pump the brakes on gluten formation: adding vinegar (which would also reduce the pH of the flour), adding sugar, pre-chilling the ingredients, and chilling the dough. For his own pie crust, he uses Beranbaum’s cream-cheese method. “It produces an amazing crust that’s flaky,” he says. “Because she’s introducing a lot of dairy fat and protein through the cream cheese into the dough, she’s reducing a lot of the gluten formation.” If readers ever run into trouble with his recipes, he makes sure to mention that he uses King Arthur Flour.

But not every recipe developer believes in making those distinctions. “I will never recommend a specific brand,” says McDowell, who also emphasizes that Beranbaum, Parks, and Sharma are right about the science. “I’m from Kansas originally, and my mom buys a flour called Hudson Cream Flour, and my grandma was using whatever was on sale. As a result, that’s the philosophy I have taken in my recipe development.”

Any good pie crust recipe is about controlling that gluten development.

She reasons that if your technique is correct, and if you’re mixing and handling the dough properly, you are going to get a good result. And McDowell tests all her pie crust recipes with several flours. “It used to be that the biggest issue that I found with people and pie was that they were either overmixing or they weren’t chilling it enough. Everyone was kind of rushing, and they weren’t giving it enough time before baking to let the fat set up and for the gluten to relax,” she says. “But the biggest problem now is hydration. People either under-hydrate or over-hydrate the pie dough.” That, of course, is related to the protein content in the flour.

Instead of specifying a flour brand to dial in the exact amount of added water, like Parks, she offers step-by-step pictures and descriptions of the right texture at each stage. She also recommends making the pie crust a day ahead, so that you and the gluten can relax a little bit and the fat can firm up, to ensure that ideal ultra-tender and flaky crust. Even better, stick with your one chosen flour, and make notes on a recipe card—the more pie crust you make, the more likely you can zero in on the right ratio for your kitchen and habits. “Pie needs patience,” she says. “It requires it.” But if all that doesn’t work out and a baker has consistent problems with dough, well, McDowell sends them to Parks’s precise recipe. This Thanksgiving, if you’re a bit rusty on pie-making and scrambling—that is, if you feel Pie Panic coming on—it might not hurt to eliminate some variables and use a recipe from a food writer who specifies which flour they used. Even McDowell can agree to that.

“I just really love pie,” she says. “And I want people to make it.”

What We Talk About When We Talk About American Food. In this column, Mari Uyehara covers American food at unique cultural moments and historical turns, great and small.