The chewing sounds were deafening—at least relative to the calm outside the 6th-century Buddhist monastery Hwaeomsa (화엄사), located in the foothills of Jirisan mountain in Korea’s Jeolla Province, a four-hour drive south of Seoul. Among the chomping (and the occasional slurp) is where I found myself on a recent morning this fall. I had traveled to Hwaeomsa with my Koreatown coauthor, Deuki Hong, and photographer Alex Lau to get a sense of how Korea’s ancient temple cuisine is prepared honestly and spiritually as a culinary practice in a workaday temple of more than 30 practicing monks and nuns—and the occasional Korean visitor looking to unplug from the daily grind.

Part of this discovery was standing in the corner of a spotless dining hall at 5:10 a.m. and watching, but also listening to, the monks eat breakfast—a well-considered buffet-style spread of deep flavor and tongue-snapping fermentation that included many of the Korean national foods (doenjang-jjigae, marinated dubu, baechu kimchi) prepared without any animal products, onions, garlic, leeks, chives, or other astringent flavors.

This isn’t the Korean monk-chef cooking . There’s no concerto of Vivaldi violins to be found. Instead, through our visits to Hwaeomsa and other temples around Seoul, we found temple food presented in multitudes—and passionate chefs preparing it—that showed as much creativity as humility. And the bowl of plant-based jjigae, shaped with a stock of kim (Korean seaweed), foraged shiitake mushrooms, daikon radish, and the chef’s stash of homemade doenjang (the foundational fermented bean paste and the base of many Korean dishes), was one of the most satisfying bowls of Korean soup I’ve ever tasted.

When Chef’s Table dropped the first episode of its third season in February 2017—a season featuring well-known American chefs Ivan Orkin and Nancy Silverton—relatively little was known outside Korea about the cuisine of Korean Buddhism, a practice first introduced 1,700 years ago. Jeff Gordinier had written about a monk-chef named Jeong Kwan and her culinary tutelage of the chef and Buddhist Eric Ripert in the New York Times Magazine two years prior, but it was the global reach of Netflix, as well as Chef’s Table’s visionary approach to food documentary filmmaking, that had the world mesmerized. “I make food as a meditation,” Kwan says at the close of the episode. “I am living my life as a monk with a blissful mind and freedom.”

The episode happened to premiere during a time of rising mainstream interest in meditation and mindfulness along with plant-based eating, and it was followed by visits to Kwan’s temple from chefs including Noma’s René Redzepi, Maison Aribert’s Christophe Aribert, and more extended residencies from well-regarded Korean chefs Mingoo Kang of Mingles in Seoul and Kwang Uh, formerly of Baroo in Los Angeles and currently of Shiku in the city’s Grand Central Market.

“The spirit of temple food that monk Jeong Kwan mentioned is respect and gratitude for all life, and all life is connected,” observes Younglim Kim, a team lead at the Cultural Corps of Korean Buddhism. “All of the monks and believers in Korean Buddhism think the same way,” she adds. “However, the food culture varies, and the temple food of Jeonggwan does not apply equally to other temples or other regions.” Kim likens the varying styles of temple cuisine to that of kimchi, noting that the food prepared by monks and nuns in northern Gangwon may significantly vary from that of the Busan region and the Jeolla region, where we were watching the nun chef Kyungjin Lee prepare morning jjigae for residents and guests.

Above: A foundational stock of seaweed, daikon radish, and mushrooms used by the cooks at Hwaeomsa. Here: Cooks plating marinated dubu and doenjang jjigae.

Kim, who leads the Buddhist Monastic Cuisine program in the Culture Corps, views the diversity of temple cuisine as a gateway for outsiders to learn about Korean heritage, partake in Buddhist traditions, and eat rustic cooking that eschews the stereotype of Korean food as exclusively a barbecue and bibimbap affair. In pre-pandemic 2019, more than 460,000 Koreans and 70,000 foreigners partook in a temple stay program—and the number is expected to grow significantly as the world continues to embrace Korean food and culture.

For our second temple visit this fall, our group traveled north of Seoul to Jinkwansa Temple (진관사), tucked on the edge of the hilly Bukhansan National Park, which, on this cloudless day, had autumn’s electric leaf display cranked up to 11. While Hwaeomsa had the feeling of a summer camp—albeit a well-ventilated, impeccably clean rural lodging—Jinkwansa was more slick and polished (Jill Biden visited in 2015), featuring a gift shop selling books and prayer beads, manicured vegetable gardens, and a hospitable and chatty monk named Sun Woo. (Ever wonder how a screening of Parasite would play to a crowd of monastic students? Sun Woo has a story.)

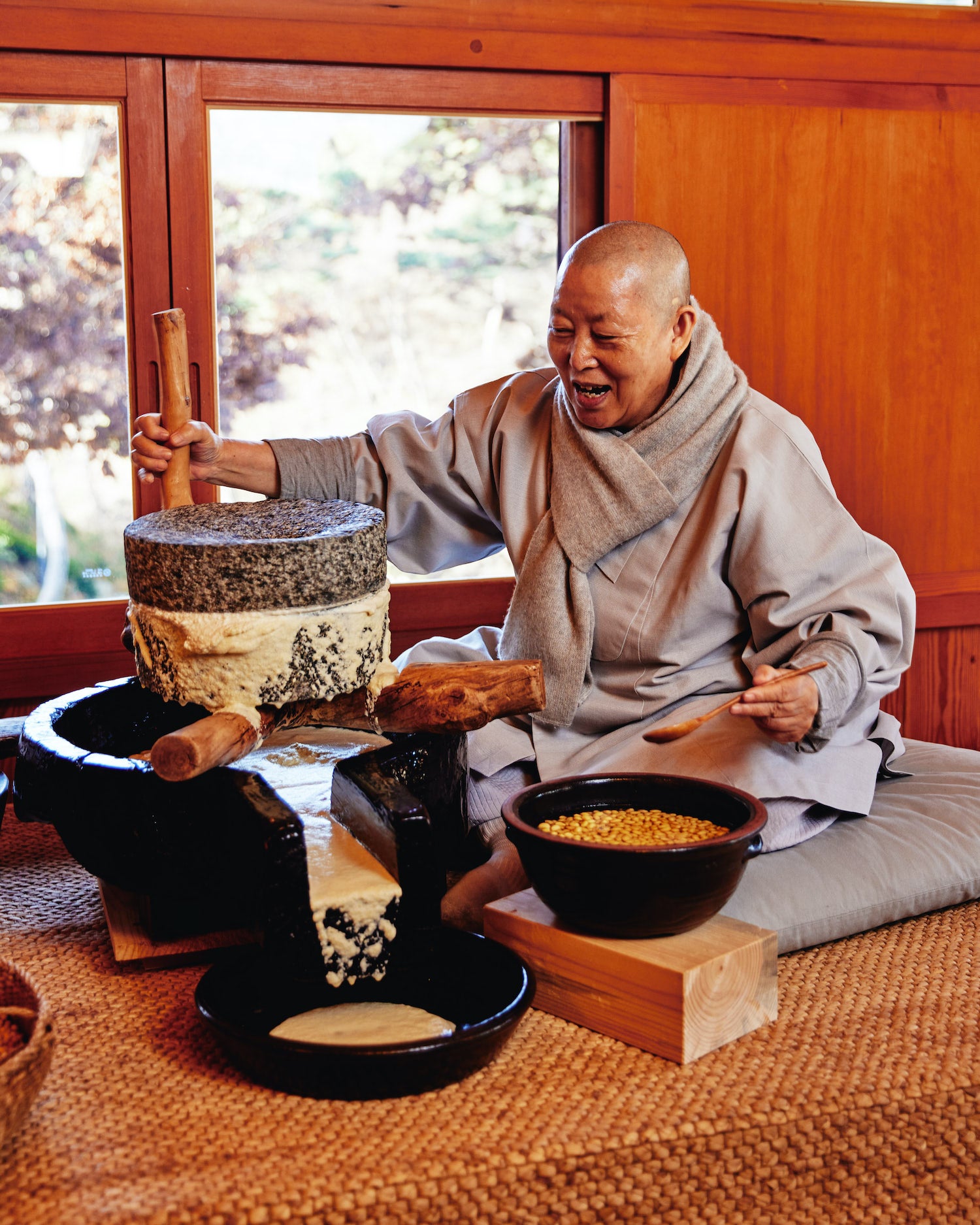

Jinkwansa is also one of the few all-female monasteries in Korea, and on the morning of our arrival, our group was led to meet with chief monk Gye Ho to talk about the rise of temple cuisine in Korea before making some fresh dubu using the most traditional methods, which involve soaked soy beans, a large grinder called a mot dol, and Gye Ho’s smiling directions.

With our group seated in a sunny room of blond woods and rare Korean flag, the national Taegeukgi that dated back to the Japanese colonial period, encased in glass across the room, I asked her how the rise of temple cuisine, and the Jeong Kwan effect, has altered the trajectory of temple food in Korea—and what it means for her personally. “It’s like a medicine for the human body,” she says through a translator. Gye Ho, now in her 70s, became a nun at age 19 and channeled a love of cooking into her practice, studying under several master monks. “Cooking is the extension of my practice. Feeding the body is the same as feeding the mind.”

Above: Jinkwansa Temple chief monk chief monk Gye Ho, making fresh tofu using a traditional mot dol. Here: Student monks harvesting cabbage for fall kimjang.

The conversation began moving in an interesting direction, broaching a subject that had been in my mind since we shared tea with an enterprising monk at Hwaeomsa the day before. While pouring us cups of maehwa (plum flower) and ssuk (mugwort) tea, he had casually mentioned his fondness for samgyeopsal (pork belly). Huh? Had he, a dedicated monk, actually consumed meat without shame? He confirmed, nonchalantly, his occasional taste for animal products, though stressing that it was very infrequent.

I had to ask Gye Ho for clarification. “Don’t kill animals or any living beings,” she says sharply, referencing both meat and fish. “But for some monks over 80 years old, it is okay for them to take in meat or fish not killed by themselves.”

While the issue of meat consumption within Korean Buddhism is complex and cannot be answered in a few interviews, it reinforces the fact that Korean temple cuisine is hardly a monolith, and that the Jeong Kwan narrative is only one of many stories. During our recent time in Korea, and on previous trips and travels, I’ve observed temple cuisine in many forms.

I was once served a small nest of sauteed burdock root, sweetened with ganjang (soy sauce) and orchard fruits, as part of a multicourse tasting worthy of high critical praise (if not only the highly dubious Michelin star). I’ve had a messy bowl of rice porridge (juk) streaked with sesame oil for breakfast. I’ve even tasted Jeong Kwan’s cooking at Le Bernardin in New York, during a special guest luncheon hosted by Ripert.

On this recent visit, I sampled the chef Kyungjin Lee’s plant-based baechu kimchi. It was sweet and fresh, only a day marinated, and it changed the way Deuki and I thought about so-called “vegan kimchi.” We’re working on a recipe now for our next book, Koreaworld.

“Over 1,700 years have passed since Buddhism was introduced to Korea,” Younglim Kim reminds me. “And since recipes are being passed down, Jeong Kwan cannot represent them all.” Nor should we expect representation from a single chef. Jeong Kwan—and her skilled marketing and publicity team—deserve credit for evangelizing temple cuisine through media and events around the world. But the future will offer so much more than a single viewpoint for an $8.99 monthly subscription.