The idea that we could extend our lifespan far beyond a century conjures images of humans stored in cryogenic chambers and decapitated heads preserved in jars, kept alive by whirring machines — in other words, science fiction.

But if a new study published Tuesday in the journal Nature Communications is anything to go by, such a dramatically extended lifetime is not fantasy at all. The study, which combines data from blood analyses and information about physical exercise to identify a new measure of “biological age.” The findings suggest there’s one aspect of human longevity that may be crucial if we are ever to meet our maximum potential. Counterintuitively, it has not to do with disease or a lifestyle choice.

“What we’re saying here is that the strategy of reducing frailty, so reducing the disease burden, has only an incremental ability to improve your lifespan,” Peter Fedichev tells Inverse. Fedichev is the senior author of the study and a researcher at the Moscow Institute of Physics and Technology. He is also a co-founder of the longevity startup Gero.

According to Fedichev and his team, humanity can go one better than merely treat diseases. In fact, if these results are validated, then our species could start living for decades longer than even the maximum lifespan they determined – 150 years.

Here’s the scoop — The study identifies patterns in aging and morbidity to draw out humans’ maximum possible “biological age.” To do this, the researchers gathered data from analyses of blood samples from 544,398 participants and combined these with Fitbit data from a separate, smaller subset of people. They then used the data to predict the onset of various diseases and to determine patterns in how people’s “biological age” seemed to change over time.

“Biological age” is essentially the age of your body’s cells, rather than your chronological age. To increase a lifespan, you need to decrease biological age compared to chronological age. Various lifestyle choices can make a difference. If you start to smoke, start a new exercise regimen, or even move to a more rural area — biological age may dip and rise over time. It doesn’t stay constant.

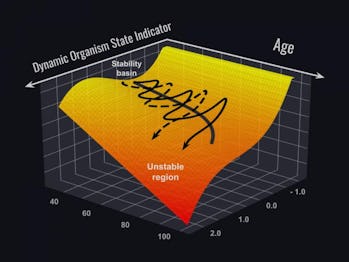

In the new study, the researchers found that one factor seemed to drive individual fluctuations in biological age, a value the researchers dub the “dynamic quantitative organism state indicator.” To understand this measure, the researchers explain it like so: As you age, your rate of recovery from different stresses (whether a disease, a lack of sleep, or even a hard workout) slows. In other words, it takes longer and longer to get back to your baseline level of resilience. Thus, individuals’ resilience to stress is the key to determining their longevity.

“If you do not target the loss of resilience, any medical intervention will fail,” the researchers write in the study.

Why it matters — If medicine advances to the point where diseases of aging can be cured, then the researchers calculate that humans may be able to age to even more than the maximum lifespan they determined without addressing resilience: 120-150 years old. Beyond that, our ability to bounce back deteriorates beyond the point of no return. Even the healthiest individuals who live the longest and resist the onset of chronic diseases cannot hope to live past this age, they say, because their resilience would have entirely depleted.

Now, 120 years of life is nothing to sniff at. But the researchers argue that if we find a way to address resilience instead of just the other problems that come with age that, to use Fedichev’s word, “disintegrate” us as organisms, then we could theoretically stall the aging process.

Fedichev recounts to Inverse a story he heard from another longevity researcher, Nil Brazilei, about a woman who was 105 and had smoked all her life.

“Every other doctor was coming to her and asking her, ‘Don’t you know that smoking is bad? Didn’t the doctors tell you about that?’” he recounts. She apparently replied: “A few of them have — and all of them are dead now.”

In other words, on an individual level, lifestyle factors may not always explain why we do or do not live to a long age. But resilience might.

What’s next — Fedichev and his co-authors don’t want to settle for the incremental increases in the average lifespan that may arise from improvements in health. We already know, Fedichev says, that on average, people live longer if they have a good diet, engage in regular exercise, are able to avoid disease, and if they are of a high socio-economic status (an important, often overlooked factor). But people who live to extraordinary ages also may carry certain genes that predispose them to longevity.

And maybe, Fedichev says, those genes affect resilience.

If we can boost resilience, then we could extend life beyond the maximum Fedichev and his colleagues identify here.

As part of his work at Gero, Fedichev and a team led by engineer Tim Pyrkov built an app, called GeroSense, that can calculate biological age using data provided by users. They hope to use the information they gather to measure resilience and ultimately, find a solution to stop aging.

Among the factors they want to look at more closely:

- Lifestyle choices

- Supplements

- Diets

- Genetic markers

“What are the more nutritional and medical interventions and eventually, what are the genetic makeup variables that may or may not influence resilience?” Fedichev asks. “Because that would be the Holy Grail of aging.”

This, he says, could come very soon. “We should be able either to use a drug, which works against the same pathway… or do the clinical trials or maybe develop something which is completely new, and put the brakes on human aging,” he says.

“I think it’s very reasonable to believe that [we will find it] — within five years or more — with this one modifier of resilience.”

Abstract: We investigated the dynamic properties of the organism state fluctuations along individual aging trajectories in a large longitudinal database of CBC measurements from a consumer diagnostics laboratory. To simplify the analysis, we used a log-linear mortality estimate from the CBC variables as a single quantitative measure of the aging process, henceforth referred to as dynamic organism state indicator (DOSI). We observed, that the age-dependent population DOSI distribution broadening could be explained by a progressive loss of physiological resilience measured by the DOSI auto-correlation time. Extrapolation of this trend suggested that DOSI recovery time and variance would simultaneously diverge at a critical point of 120 − 150 years of age corresponding to a complete loss of resilience. The observation was immediately confirmed by the independent analysis of correlation properties of intraday physical activity levels fluctuations collected by wearable devices. We conclude that the criticality resulting in the end of life is an intrinsic biological property of an organism that is independent of stress factors and signifies a fundamental or absolute limit of human lifespan.