“Peddler is a chance to breathe and have a moment of quiet, which I don’t think there’s a lot of in food media,” says Hetty McKinnon. Since McKinnon launched Peddler in 2017, the twice-yearly food journal seeks to highlight the small, “in-between” moments of food with its limited runs of 1,000 copies per issue. That is, the clanging of mahjong tiles followed by a feast of shrimp and pork-stuffed wontons, or the lingering aroma of preserved limes embedded in our memories. It’s a sharp contrast to the splashy hands-and-pans shots and prop-styled spreads we’re used to.

Though McKinnon is no stranger to America’s traditional food media landscape, and she doesn’t shy away from a bold recipe full of loud flavors. She develops recipes like creamy five spice tofu noodles for the New York Times and kimchi mac and cheese for Bon Appétit, in addition to authoring her growing collection of cookbooks: Community, Family, Neighborhood, and her newest, To Asia, With Love, which comes out this April. But in doing so, she felt there was more room to contemplate the kinds of stories that get published and who gets to tell them. The Peddler “universe,” as she calls it, is a reflection on the way we think and talk about food, free from barriers like “unfamiliar” ingredients, “30-minute meals,” prestigious bylines, and fame-driven chef personalities, told through the lens of plain text and film photography, against the backdrop of blank white space.

There’s perhaps no better embodiment of Peddler’s nostalgic and sentimental spirit than McKinnon’s well-documented love for the Chinese pairing of tomato and egg. Infinitely permutable into the form of egg drop soup or wok-seared and spooned over a bed of white rice, it’s a mixture that has appeared on the pages of multiple Peddler issues; been mentioned on the food journal’s podcast offshoot, The House Specials; and, more recently, shown up all over Instagram (also bolstered by Lucas Sin’s series of Instagram Stories featuring the beloved combination). It’s a dish that’s synonymous with everyday comfort and harnesses the power of its purity and minimalism. McKinnon and I recently caught up over Zoom to discuss her place in the high-contrast world of food media, her upcoming cookbook, and, of course, the many ways to do tomato and egg.

How do you see Peddler fitting into the other creative projects you take on, which mainly occupy the traditional media landscape?

I see Peddler as a rebellion. I don’t have to do anything that people expect me to do. It is completely my own thing. It has no commercial ties. It is completely independent. I can do whatever I want, because it is something of my own creation. And I enjoy that spirit that it has. It doesn’t look at trends; it pays no attention to famous people or famous chefs. It just is what it is.

Obviously, with the cookbooks and the freelance work and the recipe development, there are commercial ties with those. You’re coming up with a book that satisfies you personally, but you also have a responsibility to your publisher to create recipes and to create a story that will sell to your audience.

Sometimes I ask myself, “How do I exist in the American food space that wants people to really discuss their success?” That’s one of the things I’ve really struggled with, and, you know, being Chinese, being Australian—those are both cultures where you don’t talk about success very much.

Paging through Peddler, there’s a clear departure from the bright, saturated food photography and eye-grabbing design we’re used to seeing. Was that intentional?

It’s a real antithesis of what you see in food media, and that was intentional. It’s like the in-between moments of these unscripted and styled moments of our lives. That’s what we wanted to capture in the stories and in the photos. And even in the art direction, people say to me, “I can’t believe how much white space you have.” Like, what is the obsession with white space? But we want people to be able to breathe. When I first looked at a lot of the American food media, I felt suffocated and overwhelmed. Peddler is a chance to breathe and just have a moment of quiet, which I don’t think there’s a lot of in food media right now.

America is really different from Australia. When you look at some of the big publications, like Bon Appétit, so much of what was important in the food space was fame hype. One of the things I found really shocking was the way food was styled—it was so in-your-face and colorful and intentionally styled. I mean, food in Australia is also very styled, but maybe because I grew up seeing it, it wasn’t as obvious to me. But the way the colors popped was really shocking to me, actually. And so, one of the things that you’ll notice about Peddler is that there’s a lot of white space. I wanted muted colors. I wanted no styling. I wanted the photos to be really just the food. Nowadays, most of the photography we do is on film, so it has that nostalgic feel.

Does a similar idea apply to the types of recipes that are featured as well?

A lot of the work for major publications has to be: not very many ingredients, easy-to-access ingredients, you have to be able to cook it in 30 to 45 minutes, and all those things. And as a person who cooks every day, I get that. And I appreciate that. But in Peddler, we’re able to publish recipes where I think, “I don’t really care about any of those things. Whatever the recipe is works for us.” The recipes, to me, are part of the story. So there’s gotta be a reason—whatever recipe it is, the perfect recipe for that story can go in. That’s really freeing to me, as an editor, to be able to do that, to say, “Absolutely, just use the ingredient that is the most authentic to that recipe, or that is the most authentic to your family.” And without any of the worries about things being able to be cooked in half an hour and really easy to access.

Do you ever feel like there’s a tension between growing Peddler for a wider audience and maintaining creative control?

When I started Peddler in 2017, people asked me, “Why don’t you just go to someone, and they could bankroll it?” You know, they could finance it, and it could have been bigger. And the first five issues, the print run was only 1,000. That kind of small-scale, bespoke approach was what I always wanted. And when it sold out, it sold out. I really wanted it to be special for every person that bought it. When they went to buy it, I wanted them to treasure it forever.

I think that’s not something that you find that often in publishing, in general, anymore—that it’s something that people treasure. I know people collect them and they keep them. And that’s what we really wanted to create: an heirloom in a very inexpensive form. It’s so fulfilling to work on a project like that. I want it to always stay that way, without any of the pressures of all the outside world and all of that.

I doubled the print run last time with the Immigrant issue, and it was not without consideration of whether I really wanted to do that, but I recognize that with every business, with every brand, it grows. But a lot of it is because I want to keep my hands in every single aspect of it. In the first issue, I probably wrote like 80–90 percent of the issue, until we could get enough money to pay contributors, which is something we’ve always done. I also recognize that it does need to grow a little bit, but to the point where I still feel like I’m involved in its growth. I don’t ever want it to get to the point where someone else needs to do certain things for stakeholders and all of that.

People ask all the time, “Why don’t you make a digital edition? You can make extra money!” But, you know, I keep it on paper because I want to share these stories that are really special and really beyond what is available online, on your phones, on your computer. You know, what I wanted to create with Peddler is the immersive world where people feel like they can belong to that world.

As an editor, how would you define the types of writers behind each Peddler story?

I think I have an opportunity to give opportunities to people who have never written before. Like, a lot of people who contribute just email me out of the blue and say, “Oh, I saw this story. It really resonated with me.” And I say, “Well, do you want to write for us?” And it’s so shocking to them, but I’ve established some great relationships with writers who have written for me for the very first time and then have gone on to write in subsequent issues and elsewhere. And there’s such joy in giving opportunities to people who want to write and want to contribute, but never felt like there was a space or an opportunity to even ask. One of the things that we’ve tried to do with Peddler is to really foster new talent, new voices, and a different style of storytelling. You don’t need to have written for the New York Times to write for Peddler.

People send their portfolios, and I keep them all on file, but to me, it’s more like, tell me about you. What’s your story? We want to break down the boundaries of who is a writer, who is a photographer, who is an artist, who is allowed to write for whom. And the stories that resonate with me are almost instant. I can read the first sentence of a piece that someone sent to me, and I go, “This is a Peddler piece,” or, “This is a Peddler writer.” I don’t need to see a media kit or their other clippings. That’s just not my requirement for working with us.

Tell me more about your upcoming cookbook, To Asia, With Love.

When I first pitched it to my publisher, it was going to be a Chinese cookbook—and there are some very traditional recipes in there—but as I was writing it, I realized, that’s not who I am. This question of authenticity is one of the most useless questions in food, because authenticity is about being personal to you. And had I written a book that was all about traditional Chinese recipes, that book wouldn’t have been authentic to me. That was not my experience growing up in Australia, where it’s a real melting pot and there’s such a heavy influence of Mediterranean flavors. There’s a high Greek population. There’s a huge Maltese population. There are all these influences there in the foods that we eat every day.

Including . . . tomato and egg?

I’m kind of obsessed with tomato and egg. We covered it a lot in Peddler, back from the very first issue. Then we did two episodes of our podcast on it. And now it’s kind of everywhere—I just did a recipe for Bon Appétit, and Lucas Sin has his versions all over Instagram.

So lately, there’s been an explosion of tomato and egg. But when we first did it in 2017, the only article we could find on it was one that Francis Lam had written when he left the New York Times. And it was like an ode to this dish. And I remember reading it and thinking that my mom made that, and it was a very different version, but I could instantly taste it. And then when I made it for myself, it brought back all these memories.

I always say it was this weird dish in our family, because my mom never used tomatoes in her cooking. I just remember it so distinctly—it just felt like home when I cooked it. And now I make it all the time. In To Asia With Love, there’s a Chinese tomato egg recipe combined with shakshuka. So basically, I make the tomato stew as I would if I were making the base of my Chinese tomato and egg dish, and then instead of scrambling the eggs or doing an egg drop, I add the eggs whole and cook them like you would in a shakshuka. It’s a real amalgamation of all my influences—because, you know, in Australia, there are entire restaurants and cafés devoted to shakshuka. It’s really fun for me to be able to tap into all these influences in a still genuine way that’s also boundary bending.

This interview has been condensed and edited for clarity.

4 RECOMMENDED READS FROM HETTY MCKINNON

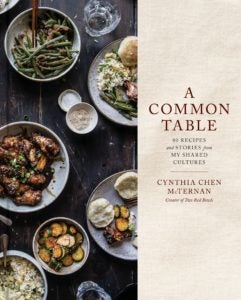

A Common Table by Cynthia Chen McTernan

Cynthia’s food is something that resonates with me, too. It’s all these influences of her childhood and her husband’s family, and I just love the way Cynthia tells the story. For me, it is one of the quietest books in the commercial cookbook space. It’s really special.

How to Eat a Peach by Diana Henry

I love the way Diana Henry leads you on a journey in her books. It makes me think, “Why didn’t I keep menus of all the dinner parties I had?” She’s lived many lives, and I just love the way she tells a story through a menu. I think that’s really unique.

Breakfast, Lunch, Tea by Rose Carrarini

This is one of the first cookbooks I ever bought. I love this book not only for the recipes, but also for the way it looks. The photos are shot reportage-style by Toby Glanville, who is not a food photographer. It’s just beautiful and immersive.

Chopsticks Recipes Vegetarian Dishes by Cecilia Au-Yeung

This book was my mum’s, and I stole it from her last time I was home in Sydney. When I became vegetarian in my teens, this is the book my mum used to learn about how to cook more vegetarian dishes. I don’t cook many dishes directly from the recipes, but I just refer to it a lot for ideas or to remind myself of dishes.

Futures is our monthlong series of interviews with the individuals and organizations reshaping the way our culture cooks, eats, and thinks about food. Read last week’s conversation with Junzi Kitchen’s Lucas Sin.