/ MELBOURNE, FLORIDA, 2021/05/17: A nurse gives a 16-year-old a COVID-19 vaccine at a vaccination clinic a

Scientists from the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention and a committee of independent expert advisors convened Wednesday to lay out and discuss everything they know about rare cases of myocarditis—inflammation of the heart muscle—in people who have recently received an mRNA-based COVID-19 vaccine, which is either Moderna’s vaccine or the Pfizer/BioNTech vaccine.

The experts focused on adolescents and young adults, who have had the highest rates of vaccine-linked myocarditis cases of any vaccinated age group. Though, to be clear, all of the rates here—even the relatively high ones—are actually very low.

Still, data on this possible side effect is accumulating at a precarious time for the country’s vaccination efforts. The Food and Drug Administration authorized the Pfizer/BioNTech vaccine for use in adolescents 12 to 15 years old just last month. So far, CDC data suggests those ages 12 to 17 have the highest rates of myocarditis cases by vaccine doses given. And the FDA is poised to review vaccine authorizations for even younger age groups in the coming months.

Many parents, teachers, and caregivers are eager to have their children vaccinated, particularly as youngsters head to summer camps and, ultimately, the start of school in the autumn. Public health experts, meanwhile, are just eager to have as many people vaccinated as possible. Their calls for vaccination have crescendoed recently as they anxiously monitor the spread of the Delta coronavirus variant, which is far more contagious than any variant before it and may cause more severe disease.

As CDC scientists and advisors gathered Wednesday, top infectious disease expert Anthony Fauci highlighted to risk of the Delta variant, particularly for children, who are largely unvaccinated. “This virus is a more transmissible virus,” Fauci said during an interview on CBS. “Therefore, children will more likely get infected with this than they would with the Alpha variant.”

But a possible side effect like myocarditis—however rare—still makes the risk-benefit analysis for vaccinating youth trickier. Children and young adults have some of the lowest relative risks for developing severe COVID-19. And although they can certainly pass the coronavirus on to others—including high-risk adults—they do not act like the germ superspreaders they sometimes seem to be during normal cold and flu seasons.

The takeaway

With the stakes high and the situation hairy, the CDC and its advisors carefully combed through the myocarditis data they have from various vaccine safety-monitoring systems. In their most firmly worded statement so far, CDC scientists concluded that the “data available to date suggest [a] likely association of myocarditis with mRNA vaccination in adolescents and young adults.”

That said, they also determined that the case rates are low and the cases are generally very mild. Nearly all of the cases recover quickly with limited treatment, and no deaths have been reported. COVID-19, meanwhile, still poses risks to children and young adults, who can end up hospitalized, in the intensive care unit, suffering with long-term symptoms, or even die from the infection. And, as more and more older adults have gotten vaccinated, children and young adults have accounted for a growing chunk of the COVID-19 cases. In May, 33 percent of all COVID-19 cases were in people between 12 and 29 years old.

Overall, the CDC and its advisors agreed that “currently, the benefits still clearly outweigh the risks for COVID-19 vaccination in adolescents and young adults.” In fact, the risk-benefit modeling analysis conducted by CDC scientists likely overestimated the risks and underestimated the benefits. Below, we’ll plow through the data they used to get there.

Myocarditis

The data rollout began with a look at myocarditis in general. First, there’s myocarditis (which is inflammation of the heart muscle), pericarditis (inflammation of the lining around the heart), and myopericarditis (inflammation of both the heart and the lining). Because the conditions were hard to disentangle in the data, the CDC clumped the conditions together despite focusing on myocarditis.

Typical symptoms of myocarditis include chest pain, shortness of breath, and heart palpitations. The condition is usually assessed and diagnosed using readings from electrocardiograms, MRIs, and looking for increased blood levels of a protein called troponin, which is a sign of heart muscle damage.

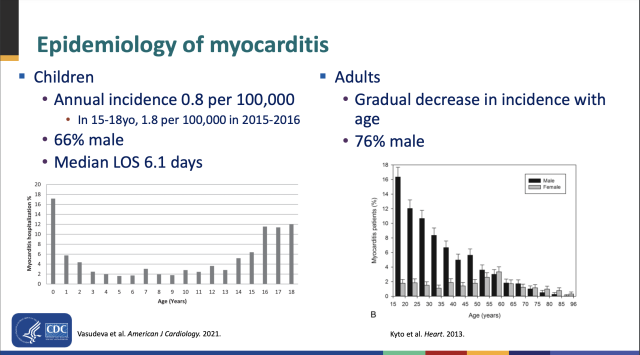

In children (from ages 0 to 18), myocarditis is typically rare, with 0.8 cases per 100,000 children over the course of a year. However, myocarditis isn’t a consistent risk for children. First, it’s more common in males—they make up about 66 percent of cases—and the risk is also bimodal with age. That is, infants younger than one have the highest cases of myocarditis. Then the numbers fall to low levels into toddlerhood and rise again in early adolescence, with the next highest incidence of cases between the ages of 15 to 18. Moving into adulthood, the incidence of myocarditis essentially falls from 20 onward, but males continue to make up the majority of cases (76 percent). It’s unclear what causes this bimodal incidence and the higher rates in males.

Cases of myocarditis can have a range of outcomes, from mild symptoms that resolve on their own to heart damage that can require mechanical support or even a heart transplant. For children hospitalized with myocarditis, the median length of stay is 6.1 days.

Many things that can cause myocarditis, including bacteria, fungi, parasites, vaccines, drug reactions, and toxins. But an immune response following a viral infection is the most common.

In data collected through June 11, the CDC had preliminary reports of 1,226 myocarditis / pericarditis cases from all age groups vaccinated after about 300 million mRNA COVID-19 vaccine doses were administered. As preliminary reports, the cases of myocarditis or pericarditis are not confirmed, and neither is any link to a vaccine dose.

From those preliminary reports, the cases largely mirrored what scientists have seen with myocarditis before. The highest incidence of cases occurred in people between 16 and 19 years old, with cases falling with age from there. The majority of the cases overall were again in males.

-

Myocarditis reports by age

-

Myocarditis case onset

For vaccine-specific data, the cases were more common after a second dose of an mRNA vaccine and tended to occur within a window of four days after the second shot. Comparing case rates by vaccine administered (Moderna versus Pfizer/BioNTech) is tricky, because the Moderna vaccine is only available for people ages 18 and up.

Crude estimates

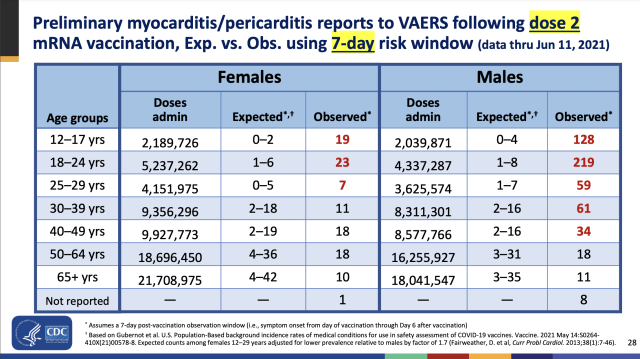

Overall, based on the preliminary reports—which again, aren’t confirmed cases—there were many more reports of myocarditis and pericarditis than one would expect to find looking at the seven-day windows after people got their second doses. For instance, for males ages 12 to 17, modeling suggested one would expect zero to four cases of myocarditis in the seven-day windows after about 2 million doses were administered. But CDC researchers collected 128 reports.

Using those preliminary reports, CDC scientists came up with crude estimates of myocarditis case rates per million doses given to various age groups by sex. The highest case rate was for males ages 12 to 17, which had a crude estimate of 66.7 cases per million mRNA doses given.

From an analysis done on just 26 medical chart-confirmed cases of myocarditis in people ages 12 to 39, the CDC scientists estimated at rate of 12.6 cases per million second doses.

In terms of outcomes, the vaccine-linked myocarditis cases have generally fared well. Studies of cases that required hospitalization showed vaccinees spent less time in the hospital than typical myocarditis patients—three or four days, rather than six. These myocarditis patients also tended to only need minimal treatment. In a look at outcomes of 323 confirmed myocarditis or pericarditis cases in people ages 29 and younger, 309 were hospitalized, but 295 were discharged. Of those 295, 218 were known to have recovered. Only nine were known to be still in the hospital, with two in the intensive care unit. Fourteen of the 323 were not hospitalized.

Risk vs. benefit

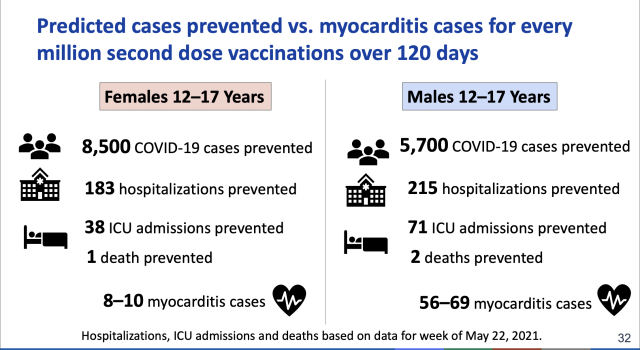

Turning to a risk-benefit analysis, CDC scientists modeled out the estimated rates of myocarditis and the benefits of highly effective COVID-19 vaccines in different groups. Even in the group with the highest risk of myocarditis—males ages 12 to 17—the vaccines looked better.

For every batch of a million second doses of an mRNA vaccine given to males ages 12 to 17, the shots are estimated to prevent 5,700 COVID-19 cases, 215 hospitalizations, seven ICU admissions, and two deaths. Meanwhile, there would be an estimated 59 to 69 myocarditis cases in the group. The picture only gets rosier in the older age groups. For males ages 24 to 29, every batch of 1 million second doses would prevent 15,000 COVID-19 cases, 936 hospitalizations, 215 ICU admissions, and 13 deaths. Meanwhile, there would be and estimated 15 to 18 cases of myocarditis in the group.

These benefits are also considered to be an underestimate, CDC scientists said. They don’t account for prevention of a dangerous inflammatory condition linked to COVID-19 called MIS-C. The model also doesn’t include prevention of so-called long-haul COVID or protection against variants. The risks may also be overestimates given that they were based on crude preliminary reports.

For now, CDC scientists say it’s clear that the vaccines’ benefits outweigh the risks, and they continued to recommend that people 12 years of age and older get vaccinated. The agency agreed while noting the need to continue collecting data, particularly on any long-term effects of mild myocarditis.

In a statement co-signed by the CDC and over a dozen other leading medical groups wrote:

The facts are clear: this is an extremely rare side effect, and only an exceedingly small number of people will experience it after vaccination. Importantly, for the young people who do, most cases are mild, and individuals recover often on their own or with minimal treatment… We strongly encourage everyone age 12 and older who are eligible to receive the vaccine under Emergency Use Authorization to get vaccinated, as the benefits of vaccination far outweigh any harm. Especially with the troubling Delta variant increasingly circulating, and more readily impacting younger people, the risks of being unvaccinated are far greater than any rare side effects from the vaccines… [Getting vaccinated right away] is the best way to protect yourself, your loved ones, your community, and to return to a more normal lifestyle safely and quickly.