Joni Mitchell’s Blue, which turns 50 years old on June 22, 2021, is an inquiry into personal storytelling, a document of the process of sharing heartache that changes every time someone hears it.

Evening Standard/Getty Images

hide caption

toggle caption

Evening Standard/Getty Images

Joni Mitchell’s Blue, which turns 50 years old on June 22, 2021, is an inquiry into personal storytelling, a document of the process of sharing heartache that changes every time someone hears it.

Evening Standard/Getty Images

I imagine Joni getting ready, again, to explain that masterpiece. She unwraps a pack of smokes.

What happened when Joni Mitchell made Blue? Accounts abound of the recording sessions at the studio owned by A&M Records on North LaBrea Avenue in Hollywood in January 1971, and of the months before, when Mitchell started sharing the songs she’d lay down in that room, saying, hey, listen to this in the hours after the canyon parties wound down; and of the time before that, when she wandered from Greek hippie communes to Paris hotel rooms collecting the sex and laughs and loneliness from which the songs would come. But the creative process is as mundane as it is miraculous. It’s dribs and drabs and then a rush and then back to staring at the ceiling, wondering if the rush will come back. Blue is an album about working through something — a heartache, people say. But it’s just as much a document of the process of sharing that heartache, an inquiry into personal storytelling itself. Until Blue, Mitchell was getting there, but she hadn’t wholly figured out what she alone could say. That’s because what each person alone can say is, in its pure state, incommunicable. Stories are what get left behind as their tellers keep living and evolving. They’re always inconclusive.

Though pristine, Mitchell’s songs here don’t feel perfect. As Sylvia Plath said, a woman perfected is marble-white, dead. Joni felt unnervingly alive when she made Blue — the lyrics in its very first song say so — and she wanted to communicate that feeling. She also had this idea that she couldn’t help but be honest. She turned her convictions into the basis of her craft. Honesty, everyone knows, is an impossible ideal, at best provisional. So Blue always feels exquisitely unfinished. Its inexhaustible immediacy proves that no artwork ever truly solidifies; it changes every time someone new encounters it. That’s its rare quality, also immanent in the brush strokes of the Japanese shan shui master Sesshu and the voice of Billie Holiday: Their makers’ mark is inscribed so delicately in these works, yet so unmistakably, that they feel immortal in a unique way. They are monuments that breathe.

Every time I listen, I feel like I’m there with Mitchell and her small occasional band as they make their choices and take their risks. Little things, turning struggle into flow: maybe the brush hitting Russ Kunkel’s drum, or James Taylor idly strumming a chord progression he’d just laid down on the album he was making across the way. Sometimes, certainly, it was Joni alone, trying out a new way to hit a low note, or to sing the word “California.” This is what people mean when they call Blue “personal.” More than most pop albums made in its era of recording-studio innovation, it’s very obviously made by people, note by note. Mainly one person, who put her process up front in a way that no one had done, exactly, before.

Despite its vibrating aliveness, over decades, even as Blue continually restored itself and redrew its borders through others’ encounters with it, the album’s reputation solidified. It became a classic — the most beloved Joni album, the most written about, the one that encapsulates the essence of her talent. Or so people say, putting pins in it. Over time, enough people put enough pins in the same spot and the music that means so many different things to different people gains an official story.

This one:

“The Blue album, there’s hardly a dishonest note in the vocals. At that period of my life, I had no personal defenses. I felt like a cellophane wrapper on a pack of cigarettes. I felt like I had absolutely no secrets from the world and I couldn’t pretend in my life to be strong. Or to be happy. But the advantage of it in the music was that there were no defenses there either.”

Mitchell said this in 1979, to Rolling Stone writer Cameron Crowe. As usual, her gift for choosing exactly the right image to put the listener deep inside a story blew everything else out of the room. It’s virtually impossible to find an account of Blue from the last 50 years that doesn’t include that quote. And of course. Blue has a particular effect on people; it softens our defenses. So, cellophane makes sense: There’s pathos in its thin plasticity. Zadie Smith, writing an essay to help her understand why, though she mostly only loved soul music, Blue got to her, made this point as well as anybody: “I can’t listen to Joni Mitchell in a room with other people, or on an iPod, walking the streets. Too risky. I can never guarantee that I’m going to be able to get through the song without being made transparent — to anybody and everything, to the whole world. A mortifying sense of porousness. Although it’s comforting to learn that the feeling I have listening to these songs is the same feeling the artist had while creating them.” Then, she reiterated the words about cellophane.

Mitchell herself clung to the image, repeating it to Vic Garbarini in Musician magazine in 1983, and Amanda Ghost on the BBC in 2007. Hell, she’d used the line “I felt like cellophane” as part of her in-concert banter even earlier, in 1974, explaining a completely different kind of song from a completely different album — the acerbic “People’s Parties” from the poppy Court and Spark. She knew a great metaphor when she’d hit on one, even if it had first occurred to her because she needed another cigarette, and looking down, she simply reflected upon the wrapper that she held in her hand.

I imagine her thinking: Cut to the feeling.

Here’s the problem with “cellophane” as the main explanation for the greatness of Blue: It gets to an essence by downplaying the long process that distilled it. Think again about what it takes to make any memorable work, not to mention a masterpiece. If you’ve ever tried, you know the best part is that seeming magic when, for a moment, what is on the inside of your brain overcomes the barrier of your hesitation and actually emerges on the page or the canvas, almost whole. When you become transparent! It really feels that way. Who can blame Mitchell for wanting to dwell on that experience? But as others have grabbed at the cellophane to understand the power of Blue, so many fingers on that one image transformed it into something other than a metaphor. It’s become the immutable fact about the album’s impact and staying power.

I want to make a different choice in trying to understand Blue. I want to honor the craft of it, the thinking, the substance. The solid work that made Mitchell able to communicate this idea she had about becoming transparent. I think that work started years before Mitchell wrote the songs that would become the album, back when she first heard Miles Davis play his horn.

Mitchell at her home in Los Angeles around 1970, when she was writing many of the songs that would eventually appear on Blue.

Martin Mills/Getty Images

hide caption

toggle caption

Martin Mills/Getty Images

I’ll start with something else Mitchell said to an inquiring writer about Blue. She was talking to the jazz critic Michelle Mercer, who wrote a thoughtful book inspired by conversations the two had one summer at Mitchell’s Sunshine Coast retreat. Mercer writes, “Joni also resents being reduced to a musical memoirist because it puts the art behind the feeling, when in her work feeling is a construct of art.” And then she quotes Mitchell on the title track of Blue: “I think the first few notes on ‘Blue’ sound like a muted trumpet tone. Just the opening part, it’s very influenced by Miles.”

What if Blue were framed not as a direct outpouring of emotion but as a response to another artist’s careful distillation of similar impulses and moods? As not only the apex of Joni Mitchell’s confessional period, but also the beginning of her jazz phase? “On Blue,” Mercer writes, “Mitchell began to integrate the music she loved into the music she made.” Mitchell is never one to go for the obvious connection, and if anyone asked her, she’d probably say no, I prefer Miles’s Sketches of Spain. But the line from one Blue to another draws itself anyway. Put that trumpet mute in the place where cellophane resides, and the masterpiece makes sense in a different way.

Miles Davis recorded Kind of Blue in 1959, in two sessions, with a band that didn’t live much beyond those late-winter weeks. Its members spanned the range of jazz expressiveness: earthy pleasure, in the horn of Cannonball Adderley; austere introversion, from the fingers of pianist Bill Evans; edgy experimentalism, in the cascades of notes let forth by tenor sax player John Coltrane. Plus a rhythm section that didn’t just hold the bottom; Chambers and Cobb could float.

Davis enlisted these men to do what Mitchell later did on Blue — make room for a clear idea. He was already one of the world’s most popular jazz musicians and an embodiment, really the embodiment, of post-war cool. The critic Gary Giddins captured the trumpeter’s allure when he wrote, long after that moment, “Miles was the first subject of a Playboy interview. Miles didn’t need a last name. Miles was an idiom unto himself.” Not unlike Joni, who became an idiom — the singer-songwriter mode, embodied — after releasing the album whose cover resembled those famous jazz sleeves a boy had placed in her arms one high school afternoon back in Saskatoon.

Kind of Blue announced what it would accomplish — something Davis had been headed toward for a while — from the first two dozen bars of its first track, “So What,” which only used two chords. This was “modal jazz,” based around the use of different scales, or sets of notes connected to a fundamental frequency, instead of chord progressions, clusters of notes that are more highly structured. Explanations of modal music can get as complicated as you want, touching upon ancient Greek philosophy, classical Impressionism, Middle Eastern drones and the twelve-bar blues. Or, keep it simple, the way jazz teachers explain modes to students: “few chords, lots of space.”

The modal approach on Kind of Blue distinguished it from the sometimes frenetic, always multi-layered sound of hard bop, which dominated jazz at the turn of the 1960s. Some thought it a step back. But within its less cluttered atmosphere, players could explore voicings that, to their own ears, often came closer to the core of thinking and feeling. Admirers of Kind of Blue — and they are legion, it’s the best-selling jazz recording of all time — have described this accomplishment in different ways. Ashley Kahn, who wrote a book on the album, says the approaches of Davis and Evans, his main compositional collaborator in the sessions, were “all about pruning away excess and distilling emotion.” Giddins describes it as a revolutionary blend of experimentation and accessibility — Zen or James Joyce, but for everyone. Darius Brubeck, jazz educator and the son of another cool jazz legend, Dave Brubeck, notes that “Kind of Blue was not so much a revolution as a realization, a supreme realization of supreme simplicity.” Any of these assessments could apply to Mitchell’s Blue as well. They illuminate the complex contours of crumpled cellophane.

When I spoke to him about the Blue sessions, James Taylor, who played on three songs on the album, made an interesting analogy. We were talking about Mitchell’s choice to use a dulcimer instead of a guitar. “Like a Japanese calligrapher, or those traditional monochromatic paintings, the limitation is something to push against, to push off,” he said. This struck me for one particular reason. In the liner notes Davis asked him to write for Kind of Blue, Evans (sort of the James Taylor of his time: tall, handsome, bookish, hooked young on heroin) began with this allusion:

“There is a Japanese visual art in which the artist is forced to be spontaneous. He must paint on a thin stretched parchment with a special brush and black water paint in such a way that an unnatural or interrupted stroke will destroy the line or break through the parchment. Erasures or changes are impossible. These artists must practice a particular discipline, that of allowing the idea to express itself in communication with their hands in such a direct way that deliberation cannot interfere.”

What Davis gave his players, Evans explained, was the parchment and instructions for the practice: uninterrupted strokes. On Blue, Mitchell issued herself the same mandate. What is cellophane, anyway? A framing material that seems to not exist. In these songs she would create structures with enough space to communicate the experience of thoughts forming. As early as her first album, Mitchell (like Davis before her) was already using a polymodal compositional approach, moving from scale to scale within songs as a way of letting seemingly oppositional tones and moods arise within the same phrases. She made this fundamental difference in her music more evident on Blue by putting aside her folkie theatricality and her Beatlesque rock edge. Mitchell’s approach on Blue seems simple to the careless ear; that’s why its radicalism is often overlooked. It is not raw. Rawness is the worst state to be in when creating something, because an unthinking person quickly sinks into bad habits. Though she brought raw feelings into the room, the fundamental challenge this music made to rock and folk norms required her and her few collaborators to be deeply mindful, to play with care and continually surprise themselves.

“I had a drum kit in the studio,” Russ Kunkel told me about his time in Studio C, which resulted in credits for him on three Blue tracks. “But if I played it at all, I played it like a percussion instrument, not like a drum kit.” He was following Mitchell’s lead. Her dulcimer, with its four strings played in open tuning, was the folkie equivalent of Davis’s muted trumpet — an instrument whose limits demanded inventiveness. Davis used mutes to create a restrained sound that resembled a torch singer’s. On the dulcimer, Mitchell learned a “slap technique” from its maker, Joellen Lapidus: She would strum and dampen the strings almost at the same time, to create an effect that evoked a drum. This innovation led Kunkel into new places.

“For me it was heaven sent,” he said of the dulcimer. “It has a choral structure but it’s also like playing a shaker at the same time, because it’s percussive on the strings, right? So she became the click.” Mitchell was the heartbeat he could follow and parry with. “I would have to be mindful to stay out of the same frequency range she was in, so I would pick lower instruments or I would play little things on the floor toms or I would play with my hands, or I’d use a percussion instrument.”

Taylor found the same freedom working with her, adding his minimal guitar parts to “California,” “All I Want” and “A Case of You.” “I said it probably too many times that Joni is like, you tap the tree, and you know, it’s like maple syrup,” he told me. “This stuff, this nectar comes out of the most unusual places.”

Joni Mitchell (right) and James Taylor singing at A&M Records Recording Studio, during the recording sessions that produced Carole King’s 1971 album Tapestry. Mitchell was making Blue, to which Taylor also contributed, in a studio down the hall.

Jim McCrary/Getty Images

hide caption

toggle caption

Jim McCrary/Getty Images

I imagine Joni and James gazing intently at each other’s fingers, moving over fretboards, articulating chords.

Sweet baby James. Most analyses of/paeans to/reflections about Blue mention that Mitchell and James Taylor were leading intertwined lives when she made it, and that this relationship occurred after some rambling on her part, which itself followed the dissolution of her more serious love match with Graham Nash. She’d lived in a cave in Greece and dallied with a redheaded rogue named Cary Raditz, and returned to find Nash just fine without her, already headed toward a new serious relationship, with Rita Coolidge. Then, hanging around the Troubadour club, she met Taylor, the new comet on the singer-songwriter scene. He was younger than her, and dangerous in a few ways: He liked drugs too much, didn’t like L.A. enough, and kept his eye out for other women all the time. But in the one way that really mattered to Mitchell — musically — none of her other early lovers matched her more perfectly than Taylor. He, too, played the guitar in a way all his own, running counterpoints across the bass strings, getting away from standard chords. And also like Mitchell, he was writing songs that felt like thoughts just rolling out, but which were as carefully composed and deeply connected to myth and legend as the blues songs that ran through his head the way jazz ran through hers.

Old love, new love. Always bringing problems. The whole cellophane thing — the vulnerability, the raw electric nerve connecting Joni’s soul to those songs — is supposedly rooted in all this romantic trauma, along with the pressures of new stardom and the after-effects of one bad acid trip. Many of the album’s most ardent fans feel that the sadness messy love generates is Blue‘s main point. However…. As Russ Kunkel said to me: “She had broken up with Graham, she had already started seeing James. Who wouldn’t be happy?” We both laughed. In 1970 Taylor was even more highly certified as a dreamboat than Nash, and a better match for Mitchell in other ways. He didn’t want to get married, and that’s why she’d left Nash in the first place. And they harmonized perfectly together; when they were inside the songs, his sense of time and hers perfectly matched.

People noticed how well paired they were. Mitchell and Taylor sang background harmonies on the version of “Will You Still Love Me Tomorrow” that Carole King included on Tapestry, which she was recording down the hall from them during the Blue sessions. She writes in her memoir, “Though James and Joni are singing on separate mics, their closeness is almost a physical presence.” One profile of Taylor from around the same time described them together on the set of the movie Two-Lane Blacktop, which features Taylor in a starring role. “In Tucumcari, Joni knitted the vest James now wears constantly and played her guitar in a field of tall grass near the set. Technicians heard strains of her soft guitar music when the wind was blowing toward them.” Like probably every interviewer before me, I asked Taylor about that vest, transformed into a sweater in the first verse of the first song on Blue, “All I Want.” He turned the familiar question into a chance to praise his long-ago lover’s ingenuity. “If she’d had steel wool she could have knitted me a car,” he said with a grin.

So maybe Joni and James were good when she made Blue. Or maybe they weren’t. Maybe he was using heroin. Maybe he wasn’t. According to the gossip that would become historical record, Taylor in his 20s was one of those icy-hot guys, like Miles, in fact, who always needed to make sure that he could get another woman if need be; like Bill Evans, he was also an off-again, mostly on-again junkie. When they were making Blue, the emotional shutdown that is addiction’s prime cause and most devastating side effect had already started pulling James and Joni apart. She’d write a great song about it, “Cold Blue Steel and Sweet Fire,” and put it on her next album For the Roses, made when their romance was definitely no more.

But if you are a lover of Blue, I want you to do something right now. Forget all that. Stop fantasizing about these two gorgeous avatars of the sexual revolution. Resist the rush you get imagining Joni’s pain. Where songs start is not that important. When Bill Evans wrote “Peace Piece,” which became the launching point for Kind of Blue‘s final track, “Flamenco Sketches,” he was spiraling into a drug dependency that would grip him for the rest of his life. He was exhausted. But even though jazz lovers know that, few talk about “Peace Piece” in terms of Evans’s personal struggle, his haunted head as he sat up all night barely moving his fingers across the song’s two chords. On the contrary, “Peace Piece” is held up as a balm whose ingredients are spiritual serenity and intellectual rigor. The key to what Evans created, as we now hear it, is not his pain but his engagement with the process of sitting with that pain until it offered self-awareness. Discipline even in the midst of crisis allowed for the miracle of “Peace Piece.” Why not acknowledge that the same is true of Blue?

It’s been difficult for some reason. Ideology, I guess. Mitchell herself has said that she bled these songs onto the pages, and that’s what everyone has chosen to remember. The master herself has come to think of Blue primarily as a wound. That’s just how we, on the gender binary, talk about creativity. Women bleed. Men forge through. But in fact, art of this caliber is always made through both the cut and the suture.

Back to James and Joni for a moment: What shows through on Blue is what they learned from each other as players. Taylor loved the acoustic blues he’d learned as a kid in North Carolina, and was a jazz fan, though he was more into the swinging eclecticism of Ray Charles than post-bop. He admired Miles Davis, and his way of leaving space in his phrasing — that indeterminate drawl — recalls the dropped time (some have called it “junkie time”) of Kind of Blue. Then there were his guitar innovations. Though he wasn’t devoted to open tunings the way Mitchell was, he’d developed a fingerpicking style that allowed him to sustain notes and smoothly move from chord to chord, a technique he inspired by what he’d learned on the instruments he learned as a child, the cello and the piano.

That Mitchell was involved with Taylor at the time of Blue makes a difference, but not because of their kisses or their fights or their mutual cruelty. The crucial turn they made together was a musical one. As rock and even folk was growing more ornate, these two went where Miles and his band had gone a decade earlier, toward supreme simplicity. Neither stayed there. Blue was a kind of oasis where they could linger in its light.

I wonder about this colossal achievement, this riddle. But as the poet Mary Ruefle said, I would rather wonder than know.

The most famous description of Kind of Blue came from the English critic Kenneth Tynan’s nine-year-old daughter. One night Tynan was listening to the album in his study and, walking past, she identified the artist. “How do you know?” Her father asked. “Because he sounds like a little boy who’s been locked out and is trying to get in.”

This story resonates in good and bad ways. It plays into some tenacious stereotypes of the Black musical genius as childlike, and gently banishes jazz to culture’s unlit backyard. Yet the child’s observation does somehow describe both the act of creation that Kind of Blue set in vinyl and one common experience of spending time with it. Denied nearly any guidance from their leader — no charts, no rehearsals — Davis’s band members each found themselves on the outside of their own preconceptions and used whatever ingenuity and strengths they could muster to get back in. But no one forced anything; Instead, each picked the lock in his own way. Spending time with the album, even 60-plus years after its release, the fan does the same. Putting aside old habits and association, the listener re-enters the process of listening.

Blue offers a similar re-entry: into the process of love. Mitchell’s lyrics would seem, on the surface, to be the most conventional element in Blue. They chase romance down vivid but not unfamiliar paths, from the lonely road to the warm bedroom to the riverbank and the bar; plenty of bards have been here before. What makes Blue’s poetry distinctive is the unfolding, or as Mitchell says in the album’s opening track, “All I Want,” the unraveling. These lines, like the improvisations in a jazz quintet, reject resolution. They run on, or end abruptly; they slip from heavy metaphor to plain talk. The musicologist David Ake has described Bill Evans’s piano playing as a long trail of themes and variations, each line seeming to generate itself out of the previous one. Mitchell’s lyrics on Blue do something similar. Every song turns around at some point and contradicts itself. A jaunty melody masks the bitter taste of grief; a hopeful declaration ricochets into self-doubt. The lyrics were not improvised, but as in a great jazz run, they expose the erratic essence of emotional experience and honor the heroism inherent in the simple human act of making sense of oneself.

She started with “All I Want,” a run-on sentence that takes her right into the arms of paradox: “I hate you some, I hate you some, I love you some, I love you, when I forget about me.” She never genuinely forgets herself, though. She’s always adding up the memories that haunt her, the ones she enjoys, the one she suppresses, observing herself as she builds these revelations and alibis. There’s “My Old Man,” for Graham, a little bitter at the core. There’s “A Case of You” for her long-gone older lover, Leonard Cohen, but also for James, a song about stamina: “I could drink a case of you, darlin’,” she brags, trumpeting a ridiculous high note, “and still be on my feet.” There’s “Little Green,” for the daughter she lost at the point of adoption, Kelly Dale, such an obvious confession and no one got it at the time. There’s “Carey,” for the red, red rogue she enjoyed and left behind in Greece. That guy will tell the tale for the rest of his life, and in the song, you can hear Mitchell happily handing it off to him.

And then there’s the title track, for James. But also for Miles, maybe. “Here is a shell for you” – I’ve always considered that line embarrassingly faux naif. But what if it’s an instruction for the listener? Here is a frame, fill it in with your own colors. “Inside you’ll hear a sigh, a foggy lullaby.” That’s a jazz lyric. Juliette Greco, Miles Davis’s lover during an idyll he spent in Europe as a young man, described him this way: “There was such an unusual harmony between the man, the instrument and the sound — it was pretty shattering.” Blue is Mitchell exploring the same harmony, between her psyche, her voice and her songs. The listener finds her own space within this flux, her own story. The one that echoes later.

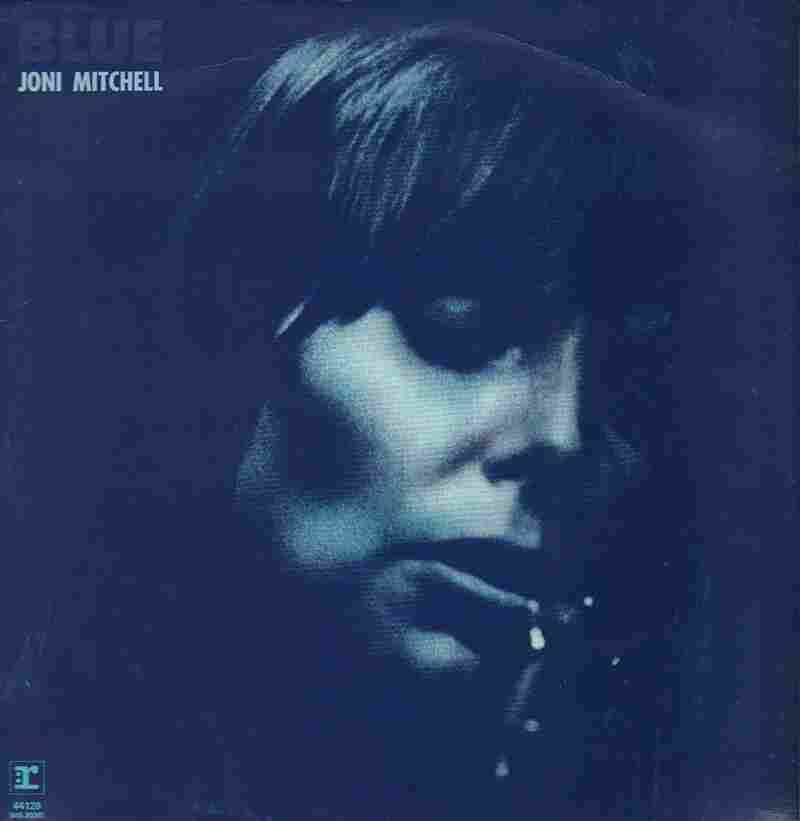

It’s interesting to think about why people decide some works of art can change their lives. What do we ask of those who make them? From some, authority: the ability to command a room, or a genre, to bend it to their will. On the bandstand, Miles Davis would often turn away from the audience, to focus on the band — but fans embraced this aloof stance as a sign he was leading them into the future. From others, sacrifice. Fifty years on, can we see Joni Mitchell’s downcast eyes on the cover of Blue, her turn inward, as a sign not merely of sorrow, but of self-possession? With Blue, Mitchell fully realized her authority; she rewrote the stories of her own life, not only in words, but by finding music that would make each word sound differently. That’s why, every time a listener turns to Blue, the path of desire and disappointment and slowly accruing wisdom the songs lay out appears in slightly different form; the songs remain in that present tense in which they were created. Maybe it’s impossible to know what happened when Joni Mitchell made Blue because every time the record plays, it’s still happening.