The overall cancer death rate dropped by about a third (32%) from its peak in 1991 to 2019, from about 215 deaths for every 100,000 people to about 146, averting about 3.5 million deaths during that time, according to the data. Most of that decline can be attributed to a drop in mortality among lung cancer patients.

The American Cancer Society projects that there will be about 1.9 million new cancer diagnoses and more than 609,000 cancer deaths in the United States in 2022, including about 350 deaths per day from lung cancer, the leading cause of cancer death.

In 2019, about one in four cancer deaths was among lung cancer patients, but lung cancer deaths are declining faster than overall trends. Mortality rates for lung cancer dropped about 5% each year between 2015 and 2019, while overall cancer mortality dropped about 2% in that time.

And the continued downward trends are reason for optimism, experts say.

“I’m an oncologist, so I’m an inveterate optimist. But I think the key message for the public is that there’s room for optimism across all types of cancer,” said Dr. Deb Schrag, chair of the medical department of the Memorial Sloan Kettering Cancer Center.

Continued progress in driving the curve down will require a three-pronged approach, with strong, unified efforts across prevention, screening and treatment, she said.

Programs targeted at smoking prevention or cessation can make a big impact, as well as annual screening, according to the American Cancer Society report.

“The data actually tells us from a wellness perspective, in every possible way, that quitting smoking at any age, at any time, at any habit level is impactful for someone’s health,” American Cancer Society CEO Karen Knudsen told CNN.

“Studies have shown that for someone who’s diagnosed with cancer, irrespective of what that cancer is — lung cancer or another cancer — if they quit smoking at the time of cancer diagnosis, it’s strongly associated with a better outcome. So, smoking cessation is important for not only preventing cancer, but for giving yourself the greatest possible chance of a good outcome if you’re being treated with cancer.”

And while screening for lung cancer has only increased slightly recently — from 2% of eligible people in 2010 to 5% in 2018 — the effects have been much larger.

About 28% of lung cancer diagnoses in 2018 were detected early in the “localized stage,” up from 17% in 2004. And more than 30% of patients were living at least three years past their diagnosis, up from 21%.

Increased screening for all types of cancer is critical, Knudsen told CNN.

“Even prior to Covid, screening uptake was not where it needed to be for the US public,” she said, with screening for lung cancer among the worst.

In her previous role at a National Cancer Institute-designated cancer center, Knudsen said she noticed that screenings dropped off each time Covid-19 cases peaked. But these delayed screening could lead to tens of thousands of preventable deaths in the years to come, and it’s “dire” that individuals make a screening plan.

“For all individuals, what I would hope is that they feel empowered to have that conversation with their primary care physician — I cannot emphasize this enough — to ask ‘what is the right screening plan for me based on my personal history and my family history and, if I know it, my genetic history?'”

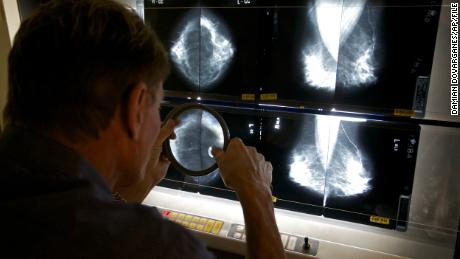

While lung cancer is the most common overall and causes the most deaths among men and women, prostate cancer is the most common type among men and breast cancer is the most common type among women, according to the report.

Advanced-stage diagnoses are increasing for both prostate cancer and breast cancer, both of which can be detected early. And cervical cancer still causes thousands of deaths, despite being almost completely preventable.

Advancements in treatment are able to effect change in a more immediate way than changes in health behaviors.

Broadly, precision medicine — understanding the molecular drivers or genetic features of cancers to more strategically treat them — and immunotherapies developed through better understanding of the immune system have been “game changers,” Schrag said.

Improvements to life expectancy after lung cancer diagnosis were mostly among those with non-small cell lung cancer and, in terms of treatment, were driven by advances in diagnostic and surgical procedures, such as video-assisted thoracoscopic surgery, as well as medical therapies such as immunotherapy that was approved by the US Food and Drug Administration in 2015.

But trends in cancer deaths are largely driven by changes in lifestyle and care over the course of decades, experts say.

“For example, when we see gains today and continued drop in lung cancer deaths, some of that is because smoking rates started to decline 20 and 30 years ago,” Schrag said. “We are reaping some of those benefits today.”

Not all long-term effects are positive. Racial and sociodemographic disparities in cancer incidence and mortality also persist due to long-lasting effects of systematic racism in the United States, according to the American Cancer Society report.

Black patients have a lower five-year survival rate than White patients for most cancer types, and Black women have a higher cancer mortality rate than any other group, according to American Cancer Society data. While the incidence rate of breast cancer is 4% lower among Black women than among White women, breast cancer mortality is 41% higher among Black women.