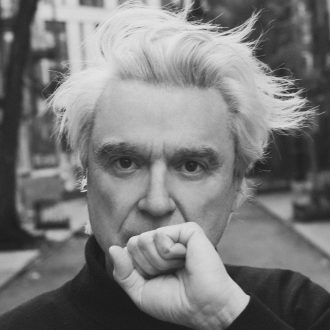

David Byrne: “Murder Most Foul,” 2020

My first exposure to a Bob Dylan song was probably the Byrds version of “Mr. Tambourine Man.” I heard it on a crappy transistor radio in my bedroom in Arbutus, a Baltimore suburb. It blew my little mind. The words were, to me at that time, impenetrable. They spoke of another world — a place both weird and magical, a bohemian land with links to the Beat poets, with whom I was familiar, a little. Late nights huddled in cafes blathering about what must have been incredibly interesting ideas. Here was a missive from that world. Not sure I was aware that Dylan wrote the song.

The music too was revolutionary to me — the chiming 12-string guitar sounded like a Balinese gamelan orchestra. I’d heard recordings of those from my local public library. God bless the public libraries. The vocal too, with its soft dreamy harmonies, was familiar — folk groups often sang in harmonies like this — but in this very different context it implied a kind of trippy reverie. So, not just the words but the sound itself was a message from another world, far from this little suburban town. Someplace I had to know more about.

A lot of ink has been spilled on Dylan’s songs and their impact over the years. I’ve learned to take some of it with a grain of salt. He’s written his fair share of throwaways and clunkers. But what encourages me is that every so often he can break the mold again and surprise us. The last song to do that for me was “Murder Most Foul,” one of his epic songs — a form he lifted from old folk ballads with their many many verses, but then he added a genetic mutation to the form — surreal imagery and metaphors rather than the traditional narratives of the old ballads.

In most of these he sets up an idea — a looming apocalypse in “A Hard Rain’s A-Gonna Fall” and the world as a twisted corrupt place in “Desolation Row” — and then it’s mostly a matter of filling in the blanks. It’s like a Cole Porter list song, in a way. Each verse being one more example of the guiding idea, and then maybe there might be a meta verse at the end to tie things up. As long as one can think of examples it can go on for a long time. I tried something similar with the song “Life During Wartime” — imagine an urban guerrilla war — then simply fill in the details in each verse.

“Murder Most Foul” starts off like one of these songs, but without the driving propulsive rhythm. It seems at first to be a conspiratorial exegesis on the Kennedy assassination… with a lot of low life humor tossed in.

“Being led to the slaughter like a sacrificial lamb

He said, ‘Wait a minute, boys, you know who I am?’

‘Of course we do, we know who you are’

Then they blew off his head while he was still in the car.”

The rhyme scheme is simple, like a children’s song or a poem from Alice In Wonderland, which makes it even funnier. I laughed at “sacrificial lamb” and “know who I am?” Dylan of course is doing his well-established “Dylan” voice and character throughout — which helps him pull off the hilarious rhymes and references.

Then little by little the song begins to veer off and begins to become something else — a meditation on the times, using the assassination as a jumping off point. The verses become littered with quotes and references to Gone With The Wind, the Beatles, Gerry And The Pacemakers, Altamont, Woodstock — on and on. Not all of it makes sense, but the sheer amount of clever comedy and portentous humor keeps me smiling. Soon it goes from third person — the story of the assassination plot — to first person. “I’ve been led into some kind of trap,” “I hate to tell you mister only dead men are free,” “I’m just a patsy like Patsy Cline” — the songwriter, and by implication all of us, are also the victims of this fiendish plot.

We’re in Dylan’s head now — the songs he heard over the years make the world in there. “Only The Good Die Young,” “I’d Rather Go Blind,” Don Henley and Glenn Frey — they’re all rattling around in there. And the rest of the song, like one of those earlier list songs, is a long list of artists and songs he’s asking Wolfman Jack to play on the radio — songs that paint a picture of what’s in Bob’s head but also of the whole 20th century, evoked through its popular songs. The Old Weird America, in the phrase Greil Marcus coined. It’s a hilarious hodgepodge of a list — jazz, gospel, pop, soul, rock — it could go on forever, and it almost does. The goofiness of the rhymes keeps it from getting pretentious and tedious — it’s deep and dark, but there’s joy and jokiness here too.

The music is key. It ebbs and flows but never establishes a clear delineated groove. I suspect if it did it would gain some temporary energy but soon it would get repetitious and we’d lose interest.

So this song was inspiring to me — not as earth-shattering as “Mr. Tambourine Man” was to a wee lad, but important in a different way. I hear Dylan finding, at this stage in his career, a new way to approach these epic songs. He’s not done exploring yet. That’s inspiration for me for sure. Not that I want to do a song like this — he’s already done it — but the idea that around the bend I might find something new that I’ve never done before keeps me pushing on and hopeful.