Ask about moqueca de peixe, the lush Brazilian seafood stew slippery with coconut milk and dende oil, and Jessica B. Harris, culinary historian, author, and legend of food scholarship in the United States, might reference Shakespeare.

“‘Tell thee, Macduff was from his mother’s womb / Untimely ripped,’” she quoted from Macbeth, when I called her at her home on Martha’s Vineyard. She had been telling me about her time more than three decades prior in Bahia, the northeastern Brazilian state famed for its version of the dish made with tropical fruit and rust-colored palm oil. “If you look at Bahia’s topography, if you look at the dirt, the palm trees, the water, Bahia feels like it was from Africa’s womb untimely ripped,” Harris said. “Bahia is where Brazil turns its African face to the world.”

Slavery was legal in Brazil for approximately 350 years, and, according to Brazilian historian Emília Viotti da Costa, 40 percent of the 10 million enslaved Africans who were brought to the New World were dragged to Brazil. Bahia and its capital, Salvador—a port with a current population of around 3 million—were the arrival epicenter. Moqueca speaks of two worlds, the old and the new, and that dialogue, that mingling, is the thesis of Harris’s 1989 book Iron Pots & Wooden Spoons. The slim work belies the miles traveled. Harris’s research jets from the Gambia to Guadeloupe, from Senegal to Alabama, from Benin to the Bahamas. As she notes in the book’s standout introduction, “In truth, and in more ways than one, African cooking on the continent and in the New World can be summed up in one sentence: Same Boat, Different Stops.”

To make moqueca, you cook a sturdy white fish, like cod, or shellfish (often shrimp) with onions, bell pepper, and tomato, then finish with wallops of coconut milk and orange palm oil. Bell pepper and tomato: plants of the Western Hemisphere. Palm oil: native to western Africa, its appearance in moqueca a vestige of slavery’s Middle Passage. “The connection is so seamless,” says Harris, who, at 72, moves between Martha’s Vineyard, New Orleans, and Brooklyn. “A little bit from each side, so it seems like moqueca lives in the space between them.”

I asked Dr. Harris for other recollections of Bahia and moqueca from her research visit. “Oh god,” she said with a groan. “I wouldn’t even know where to begin. This was more than thirty years ago.” I should use “Jessica,” not “Doctor,” after she forbade me years ago from calling her “Doctor” and insisted I call her “Jessica.” I slip into honorifics sometimes. It is what it is. Dr. Harris, er, Jessica, then spoke of the traditional, ritual ways of cooking a dish like moqueca over an open fire. “It’s an easy dish, in that sense.”

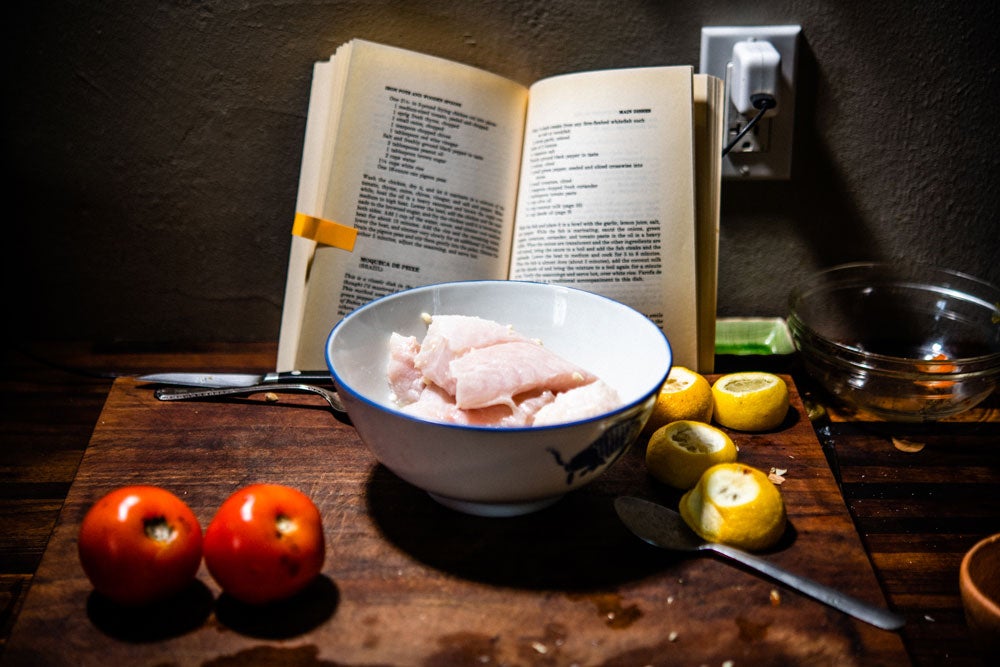

I have no open-fire stove in my New Orleans kitchen. I cut the onion, green bell pepper, and tomato into slivers: half-moons for the onion and tomato; whole, crenated rings for the bell pepper. As the chunks of cod marinated in garlic and lemon juice, I sautéed the onions until they were almost soft and translucent, then I added the tomatoes and bell pepper, along with cilantro, tomato paste, and fresh chile—my addition, because I like a glimmer of heat. In a handful of minutes, a thick sauce manifested. Into the sauce the fish went, marinade included.

When the fish is nearly cooked, you add loads of coconut milk and a third as much dende oil. Take stock, quick-like, before the two colors converge! The heavy off-white of the coconut milk eddies around the red-orange of the palm oil—a complement in contrast.

Harris spoke of the Bahian region’s penchant for yellow-orange foods, beginning with urucum (achiote), which may have led to the cuisine’s easy adoption of West African dende oil. She spoke of Candomblé, the Afro-Bahian religion that “influenced all of Afro-Bahian food and culture.” Her mind roamed; she drew plangent connections across ingredients, color, and religion from her past research, while, in the present of late 2020, she bemoaned the wearying isolation of the coronavirus pandemic. We all know there are lifetimes and lifelines in every dish, every recipe. Would that we all could tell their stories like Jessica Harris does.

A Kitchen in New Orleans. Many years of eating, cooking, and writing about food have left Scott Hocker with many stories to tell. In this monthly column, he re-creates a dish tied to a distant, or sometimes recent, food memory.