The world’s first clinical trial for a coronavirus drug made from antibodies got off to a promising start in Jerusalem, with all three patients involved released from the hospital days after receiving it.

The patients were in moderate condition, with COVID-19-induced pneumonia, when given the drug, manufactured from antibodies found in the plasma of recovered coronavirus patients, earlier this week.

“The response was, in my eyes, it was almost a miracle — they received it and they are now home,” said Zeev Rothstein, director of Hadassah Medical Center in Jerusalem, which worked with the biopharmaceutical firm Kamada to develop the drug, and is now running the clinical trial.

The trial started last Thursday, and involves treating 12 patients, in batches. The first batch consisted of three patients, the last of whom was discharged on Wednesday. Doctors say that the patients are well enough to rest at home, but have not yet tested negative for COVID-19.

Rothstein commented: “I don’t know if it’s beginners luck, but we are very enthusiastic. For a physician to see such an improvement in a very short period of time is astonishing.”

Zeev Rothstein, director of Hadassah Medical Center (courtesy of Hadassah Medical Center)

He said he is “trying to be cautious,” as he has been disappointed by some treatments that have been touted for the coronavirus, but added: “If trials show the efficiency we expect, it won’t only improve patients’ situation but could change the attitude to coronavirus in Israel and in the world.”

Rothstein expressed hope that other Israeli hospitals will join this phase of testing, both for the sake of patients who may benefit and to bolster the reliability of results.

Kamada was the first company in the world to manufacture a coronavirus drug from antibodies and has now become the first company to clinically test such a product, said its CEO, Amir London. He added that the drug, which is currently being tested on active patients, will also be examined for possible preventative qualities.

In May, The Times of Israel was first to report on plans for such a treatment based on Israeli blood samples.

London is not commenting yet on the clinical trial, as he is waiting on data from all 12 patients who are to receive the treatment in this first phase of testing.

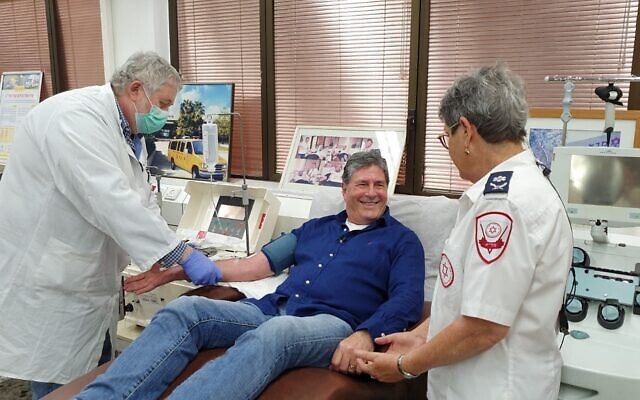

A recovered coronavirus patient (center) donating plasma for Israel’s experimental antibodies treatment. (Magen David Adom)

Israeli patients have been given antibodies from recovered patients since early in the pandemic, but this drug, while based on antibodies, is “very different,” said London.

He commented: “We use convalescent plasma as our raw material, but then it goes in to pharmaceutical development and processing to become a drug. When you give an infusion [of regular antibodies] you don’t know exactly what you are giving.”

With the new product, he said, the manufacturing process ensures the quantities of antibodies are pre-defined and standardized and patients are delivered an “anti-viral treatment that can reduce the viral load.”

Amir London, CEO of the Kamada biopharmaceutical firm. (courtesy, Kamada)

It is being tested on moderate patients, because they are believed to more consistently have high viral loads than serious patients, who are sometimes battling the after-effects of the virus rather than the virus itself.

“We are giving it to moderate patients, with pneumonia, but who aren’t ventilated yet,” London said. “We want to catch them while they’re still highly vital, but before deterioration, and to treat that viral phase with an anti-viral treatment.”

The product is hyperimmune globulin, sometimes referred to as a passive vaccine. It is called passive because unlike a regular vaccine, which prompts the body to create antibodies to fight viruses or bacteria, it contains pre-formed antibodies.

Hadassah, together with Magen David Adom, which runs Israel’s blood service, started collecting plasma from recovered patients three months ago, for the development of the drug. Hadassah’s statement said that it did so, “despite initial opposition from the then-director general of the Health Ministry,” referring to Moshe Bar Siman-Tov, who resigned in May.

Jerusalem’s ultra-Orthodox community was key to facilitating plasma collection needed for the drug. Upon realizing that large amounts of antibody-containing plasma was needed in a short time, Hadassah turned to Haredi leaders through the Yad Avraham nonprofit. Rothstein said: “We went directly to the Haredi community, where coronavirus was prevalent, and the idea of people helping one another brought a good response.” Some 126 volunteers came forward.

Kamada, which has long manufactured an antibody treatment for rabies with approval of America’s Food and Drug Administration, modified its product to treat the coronavirus.