The global tally of unexplained hepatitis cases in children has reached about 450, including 11 reported deaths, according to an update from the European Centre for Disease Prevention and Control.

The cases come from more than two dozen countries around the world, with about 14 countries reporting more than five cases. The countries with the largest case counts so far are the United Kingdom and the United States.

In the UK, officials have identified 163 cases in children under the age of 16, 11 of whom required liver transplants. Last week, the US Centers for Disease Control reported 109 cases under investigation in children under the age of 10 from 25 states. Of those cases, 14 percent required liver transplants, and five children died.

Fourteen countries in the European Union reported about 106 cases collectively, with Italy (35) and Spain (22) reporting the largest tallies of EU member countries. Outside the EU, officials have reported cases in Argentina (8), Brazil (16), Canada (7), Costa Rica (2), Indonesia (15), Israel (12), Japan (7), Panama (1), Palestine (1), Serbia (1), Singapore (1), and South Korea (1).

The 11 deaths were reported in Indonesia (5), Palestine (1), and the US (5).

The cause of the severe hepatitis—liver inflammation—remains a mystery, despite the growing tally. Some of the cases have been identified retrospectively, dating back to October 1, 2021.

Health officials worldwide have been on the lookout for child cases of acute hepatitis that can’t be explained by common culprits, such as hepatitis viruses A, B, C, D, and E, which are known to injure the liver. Those with cases also have elevated levels of liver enzymes.

“At present, the leading hypotheses remain those which involve adenovirus,” Philippa Easterbrook, a senior scientist with the World Health Organization, said Tuesday in a press briefing. “But,” she added, “I think [there’s] also still an important consideration about the role of COVID as well, either as a co-infection or as a past infection.”

Easterbrook noted that about 70 percent of the cases that have been tested for an adenovirus have tested positive, and subtype testing continues to commonly turn up adenovirus type 41.

Data coming soon

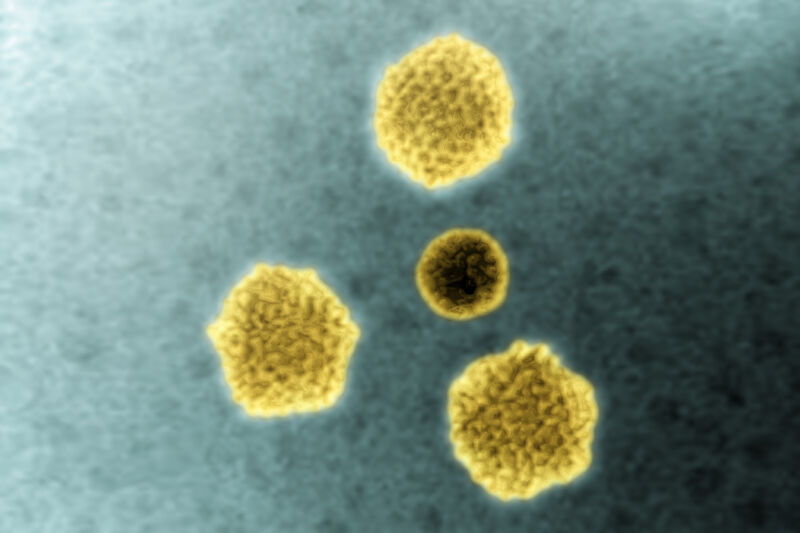

Adenoviruses are not known to cause hepatitis in healthy children, though the large family of viruses has previously been linked to liver damage in children with compromised immune systems. Adenoviruses often cause common respiratory infections in healthy children, while type 41 is linked to gastrointestinal illness.

Liver biopsy data so far has not turned up adenovirus in the livers of affected children, raising further questions. Moreover, adenoviruses are quite common in children, and some of the hepatitis cases occurred while adenovirus transmission in the general population was high. This raises the possibility that the detection of adenovirus is merely incidental and not the cause of the liver injuries.

In the press briefing Tuesday, Easterbrook noted the possibility, saying, “Hopefully, within the week, there will be data from the UK on [an] important case control study comparing whether the detection rate of adeno in the children with liver disease differs from that in other hospitalized children. That will really help hone down whether adeno is just an incidental infection that has been detected or there is a causal or likely causal link.”

Otherwise, officials have reported that the cases are sporadic and unlinked, with no known common exposures to medicines, foods, drinks, toxic substances, or travel. The US CDC has also ruled out bacterial infections, urinary tract infections, autoimmune hepatitis, and a rare genetic condition called Wilson disease, based on data from cases in Alabama.

According to Easterbrook, testing has found that about 18 percent of cases are positive for SARS-CoV-2. However, the US CDC has ruled out SARS-CoV-2 as a possible direct cause of the cases, noting that the first nine cases identified in Alabama were all negative for the virus. In a press briefing last week, CDC Deputy Director for Infectious Diseases Jay Butler said that the agency is still keeping open the possibility that previous SARS-CoV-2 infections could play a role in the cases. Studies looking at past infections of SARS-CoV-2 in affected children are now ongoing in the US and elsewhere.