In Pierre Franey’s debut installment of his “60-Minute Gourmet” column for the New York Times, published in November of 1976, the celebrated French chef’s recipe was hardly French at all. He called the dish Crevettes “Margarita.” A friend had been sampling margaritas, Franey writes, and challenged him to create a recipe with shrimp using the same ingredients as the margarita cocktail. The dish incorporates the hallmarks of classic à la minute French sauces—butter, shallots, and heavy cream—but in a pan spiked with a stiff shot of tequila, where the shrimp bathe briefly before being finished with a squeeze of lime, crescents of sliced avocado, and finely chopped cilantro.

Franey would never have dreamed of serving a dish like this at Le Pavillon, the cathedral of French haute cuisine where he worked under the tempestuous restaurateur Henri Soulé. At the time, Le Pavillon was considered by many to be New York City’s finest French restaurant, perhaps even one of the finest in the world. Soulé’s kitchen was no place for haste or improvisation. There, Franey presided over an austere menu of French classics like steak marchand de vin and duckling à l’orange as well as an elaborate chef’s buffet overflowing with imported caviar, pristine shellfish, foie gras terrines, and cold omelets layered with fresh crabmeat.

His unorthodox shrimp “cocktail” recipe may have seemed out of character for a French chef with his pedigree, but Franey embraced his new role as an ambassador for quick and efficient cooking for a curious audience of Times readers. The inaugural column welcomed them with a rubric that would define the rest of his career: “With inventiveness and a little planning there is no reason why a working wife, a bachelor, or a husband who likes to cook cannot prepare a meal in under an hour.” Franey’s “60-Minute Gourmet” ran for a staggering 17 years and popularized the concept of cooking on the clock, foreshadowing many of today’s set-it-and-forget-it trends like sheet pan recipes and one-skillet meals.

According to Franey’s daughter Claudia, the genesis of the 60-minute recipe column wasn’t by chance. Arthur Gelb, the legendary New York Times editor, had come to visit Franey in Long Island one day when Pierre, an avid fisherman, cooked a freshly caught, local fish for him and his wife, Barbara. Gelb was so impressed by the brevity of his process that he suggested Franey do a series of simple recipes for the new Times Living section scheduled to launch in late 1976.

“I think a light bulb went off with the Gelbs,” Claudia Franey recalls. “Like ‘Why don’t we show this in the New York Times? This is great!’ You don’t have to plan too much ahead, and you can do a meal in under an hour.” Initially, Franey objected to the use of the word “gourmet” in the title—he found it pretentious. But the Gelbs insisted. Franey would later dedicate the first volume of the 60-Minute Gourmet cookbook to Barbara Gelb as a show of gratitude.

Franey’s other daughter, Diane, credits Don Hewitt, the creator of the CBS news program 60 Minutes and a friend of her father’s, with helping hatch the plan for Franey’s new column. It’s almost too simple to believe. “He lived in Bridgehampton,” Diane, who now lives in her childhood home in East Hampton and works as a nurse in Long Island, says. “And he got my father interested in the “60-Minute Gourmet” idea based on the success of his TV show. He said, ‘Why don’t you do recipes people can make in sixty minutes?’” Decades later, Diane treated the elderly Hewitt as a visiting nurse, and he confirmed the veracity of the story.

“At Howard Johnson’s, everything had to be recorded. This was important for [Pierre] eventually when he wrote recipes for the New York Times.”

In 1960, Franey had a public falling out with Soulé over wages and left Le Pavillon in a fit of pique. Only eight months before abdicating his position as chef, Franey had hired a fresh-faced, 24-year-old Jacques Pépin, who’d recently arrived in New York City to find work as a cook. Although the two had known each other only a short time, Pépin turned down an invitation to cook in the Kennedy White House to join Franey as a corporate chef for Howard Johnson’s.

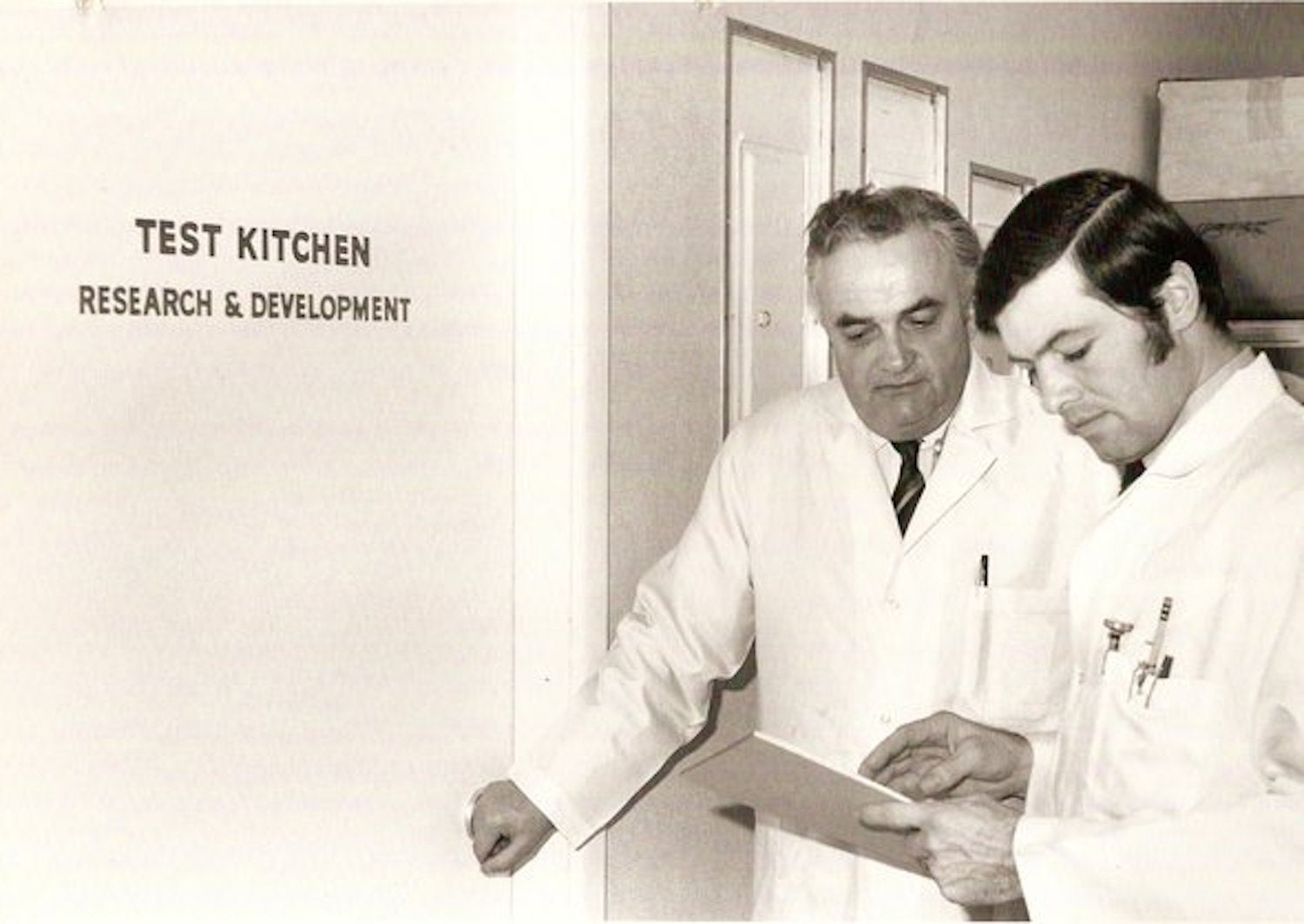

Howard Johnson, Sr., who owned a vast empire of American family restaurants known for “tender-sweet” fried clams and butterfat-rich ice creams, had become a regular at Le Pavillon, and he lured Franey to help overhaul the menu across his nationwide franchise. Franey spent over a decade working in research and development as a vice president for Howard Johnson’s, transforming its culinary program by moving away from processed foods and toward scratch cooking, with Pépin as a trusted confidant.

“Pierre became like an older brother for me,” Pépin says. “He was from Upper Burgundy; I was from Lower Burgundy. We both left school at thirteen to start our apprenticeships.” Cooking together at Howard Johnson’s taught the two French chefs to think more pragmatically about recorded recipes. “We never cooked with recipes at Le Pavillon. In professional kitchens in France at the time, no one cooked with recipes,” Pépin remembers. “At Howard Johnson’s, everything had to be recorded. This was important for [Pierre] eventually when he wrote recipes for the New York Times.”

Ruth Reichl, the former editor of Gourmet magazine and the New York Times restaurant critic from 1990 through 1993, remembers the ’70s as a time when Americans began to take cooking more seriously. Gourmet had a column called “In Short Order” that was inspired by Franey, featuring recipes that could be made in 45 minutes or less. “Food itself became a part of popular culture. Suddenly, what was for dinner really mattered,” Reichl says. “What Pierre recognized—and what the Times recognized—was that what people in America wanted was changing. People wanted really good recipes that they could make quickly. The irony is that the 60-Minute Gourmet seems like a lot [of time] now.”

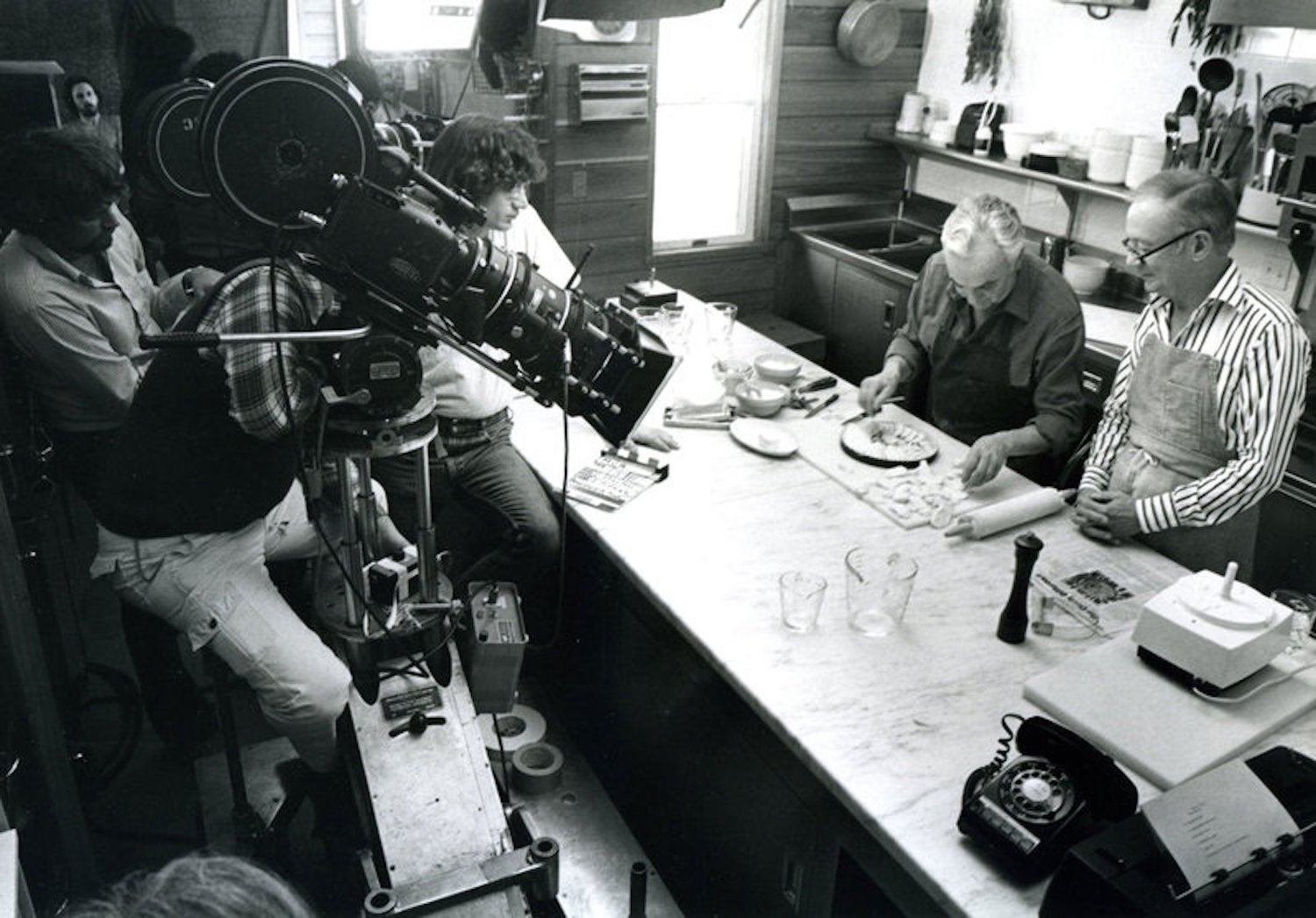

Prior to collaborating with Franey on the 60-Minute Gourmet, the indelible New York Times food editor Craig Claiborne had written an amorous feature about the cuisine at Le Pavillon under Franey’s direction in April 1959. The two became friendly, and Claiborne recruited Franey as a culinary adviser for his own recipe column.

Among hundreds of others over Claiborne’s 30-year career with the Times, he and Franey developed many of the most popular New York Times recipes together, including a simple interpretation of Billi Bi—a creamy mussel chowder made with white wine, herbs, and cayenne pepper emulsified with a tempered raw egg yolk—anointed a “Times Classic” in 2015. It was one of Franey’s personal favorite dishes, according to his daughters, so much so that he named his Boston Whaler in East Hampton the Billi Bi.

Claiborne and Franey’s rapport became strained over the years, both professionally and personally, culminating in Claiborne leaving the New York Times in 1986. But Franey continued filing weekly recipes with Bryan Miller, who joined the Times in 1983. By then, the 60-Minute Gourmet cookbooks, based on Franey’s popular columns, were already best sellers. The first volume, published in 1979, offers distilled versions of French classics like filet of sole Grenobloise and moules poulette. But you’ll also find an Americanized steak au poivre made with hamburger meat and a creamy chicken fricassée that a Southern grandmother might make.

The sequel, More 60-Minute Gourmet, broadened the scope beyond his French oeuvre, including his versions of Swedish meatballs, chili à la Franey (his 60-minute interpretation), arroz con pollo, and moussaka, although Franey sheepishly admits in his notes for the latter that the recipe pushes the limits of a kitchen hour.

“What Pierre recognized—and what the Times recognized—was that what people in America wanted was changing. People wanted really good recipes that they could make quickly.”

Franey’s work ushered in an era in cookbooks and recipe columns that centered convenience. Ruth Reichl cites Rozanne Gold’s Recipes 1-2-3 cookbooks as exemplary of this new emphasis on making life simpler in the kitchen. Gold’s cookbook series, consisting of recipes with only three ingredients, was the inspiration for Mark Bittman’s column “The Minimalist,” which first appeared in the New York Times in 1997. Not long after that, in 2001, the world was introduced to Rachael Ray’s “30-Minute Meals.” Today, an entire cottage industry exists around shaving minutes off the cooking clock, from viral baked feta cheese pasta recipes to no-bake Mason jar desserts.

Gold credits Franey for helping bridge the gap between the restaurant chef and the home cook. At the time, she says, preparing a delicious meal at home in less than an hour was empowering. “I don’t really feel that the 60-Minute Gourmet had only to do with convenience. It had to do with a construct—putting a frame around cooking.” The microwave oven was worming its way into the mainstream, and drive-throughs permeated the sprawling suburbs. Franey’s work foreshadowed the kind of quick-fire recipes that have made products like the Instant Pot and air fryers so successful today. These modern cooking contraptions have taken off because of the thousands of easy recipes designed for them, not necessarily because they’re inherently easy to use.

The push toward convenience in recipe writing still exists at the New York Times. Of Alison Roman’s recipe for sheet-pan trout, Sam Sifton, then the NYT food editor, remarked in 2018: “Remember the old ‘60-Minute Gourmet’ columns of Pierre Franey? I think Alison is an heir to that tradition.” In Roman’s biweekly column for the Times, she described her cooking style as: “looks impressive but requires less effort and time than you’d imagine.” Almost a half-century later, the wisdom behind Franey’s brand of convenience cooking is still the Times Food section’s North Star.

Colu Henry, author of Back Pocket Pasta and the upcoming Colu Cooks: Easy Fancy Food, has contributed over a hundred recipes to the New York Times Cooking section. She recalls an exchange about her popular Roasted Tomato and White Bean Stew recipe where her editor advised against roasting the tomatoes first. “They’re still very into time and generally want recipes capped at under 45 minutes, including prep,” Henry says of her marching orders from the NYT. “If there was a way to cut a step or combine them, it was always encouraged. For the most part, they’re looking to ease home cooks.”

In his farewell column, Franey revisited his Crevettes “Margarita” recipe, tweaking it slightly—a skinny margarita, if you will—with half-and-half in lieu of heavy cream. American audiences were eating healthier, which made Franey’s goodbye somewhat circumspect. “Back in November 1976, when the 60-Minute Gourmet appeared in the first Living Section of the New York Times,” he wrote, “the notion of preparing an entire home-cooked meal in less than an hour was formidable. Today, with so much time-saving equipment available and the predilection of Americans for simpler, lighter fare, meals in half that time are almost routine.”

Trends in cooking had changed a lot over those 17 years, but the 60-Minute Gourmet changed the way people cooked. “I may have been teaching others to cook with a dedication to streamlining,” he writes in his 1994 memoir A Chef’s Tale, “but the effort has taught me, too, forced me continually to adjust my repertoire.”

Pierre Franey died in 1996 at age 75, doing what he loved most. Aboard the Queen Elizabeth II en route to England, he passed away of a stroke shortly after giving a cooking demonstration for passengers. His culinary legacy lives on in the brand of convenience cooking he helped pioneer and the generation of cooks he influenced, but also in his children’s home kitchens. His daughters still gather frequently, along with their brother, Jacques, to resurrect their father’s old recipes. Often, after cooking them, they publish their favorites to a website they created in his memory in 2014.

According to Emily Weinstein—who recently took the reins as editor of NYT Food and Cooking—readers still email about Franey recipes years later. “Those dishes are still beloved,” says Weinstein. “He had an eye toward simplicity, and that makes a lot of his recipes feel fresh, even though they are decades old.”