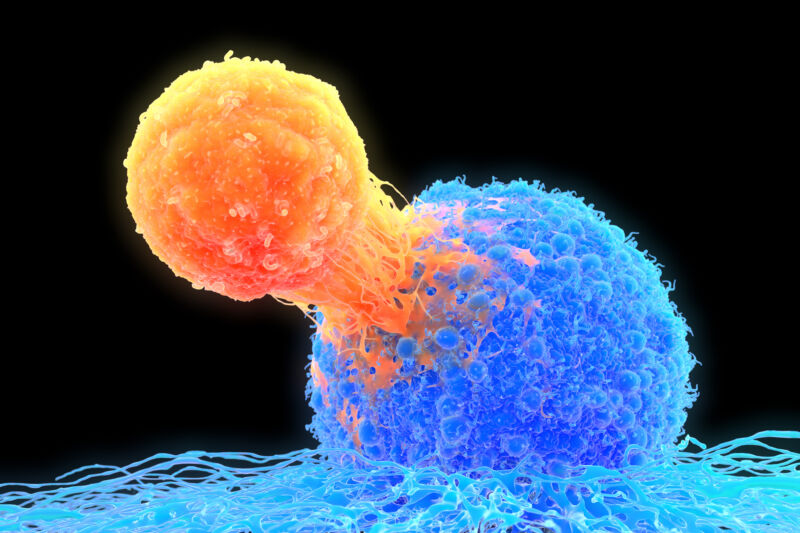

/ False-color image of a T-cell (orange) latching on to a cell in preparation for killing it.

From the start, the omicron variant had experts worried because its version of the virus’s spike protein carried mutations in many of the sites that are recognized by antibodies. This meant that antibodies generated to combat earlier variants like delta were less likely to recognize the newcomer. The fears have played out in the form of lowered immunity to omicron and the failure of some antibody-based therapies.

But all the worries were focused on the immune system’s antibody response. The immune system also produces T-cells that recognize the virus, and wasn’t clear how omicron affected their response. Based on two recently published papers, the answer is “not much at all,” which could help explain why the vaccines continue to protect from severe disease.

Those other cells

The T-cell-based immune response works very differently from that of antibody-producing cells. It relies on the fact that all cells chop up a small fraction of the proteins they make. Specialized proteins then grab on to some of the resulting protein fragments and display them on the cell’s surface. Once on the surface, they can be recognized by a receptor on the surface of T-cells.

The immune system gets rid of any T-cells that recognize proteins normally made by human cells. But when a pathogen is present, cells will start displaying some of its proteins on their surface. T-cells can recognize these proteins as foreign and trigger a number of responses. Helper T-cells make signaling molecules that rev up other immune cells, including those that make antibodies. Killer T-cells can latch on to the surface of infected cells and kill them.

T-cells are essential for the immune response; the absence of helper T-cells is what causes the immune deficiency seen in AIDS patients. But their role in fighting off SARS-CoV-2 was less clear, as protection from infection was largely correlated with levels of antibodies.

The lack of clarity was made worse by the fact that T-cells are hard to study. A simple blood sample is all we need to obtain enough antibodies to see what they stick to. T-cells can also be obtained from a blood sample, but they must be grown in culture for weeks to get a sense of what they might be responding to.

Nevertheless, two different groups have obtained T-cells from a combination of vaccinated and infected individuals and have tested the T-cells for their response to omicron.