This has to be the most picturesque sale of the decade. It involves a great Roman family, a Playboy pin-up who has done business with Donald Trump, an inheritance dispute, a magical (literally) masterpiece by Caravaggio, wonderfully frescoed interiors by Guercino, numerous ancient Roman sculptures, and a 2,200 sq. m-building in the centre of Rome, all in one lot estimated at nearly half a billion euro.

The online auction of the Ludovisi Casino (in old Italian, a small suburban plaisance, not a place for gambling) starts on 18 January at 3pm CET and lasts 24 hours. It is being conducted by the Rome Tribunal, which deals with forced sales, and bidding will start at €353m, with an estimated end price of €432m.

Whatever the outcome, the sale raises two questions. First, how do you value a work of art that is part of a building and cannot be resold separately from it. Second, what does this episode say about Italian inheritance laws and the country’s guardianship of its vast artistic heritage.

The Ludovisi Casino is in a garden behind the Via Veneto in Rome (made famous by Fellini’s La Dolce Vita) and near the US embassy, itself once a Ludovisi property. With later extensions, the core of the Casino was built in the late 16th century for Cardinal Francesco del Monte. In 1597, he commissioned his protégé, the 26-year old Caravaggio, to execute a 300cm x 180 cm ceiling painting in oils for his Laboratorio, where he conducted experiments according to the theories of Paracelsus, the Swiss doctor, alchemist and astrologer (d.1541), who believed that the world was governed by natural magic connecting it to the stars, and that its main principles were salt, sulphur and mercury in addition to the traditional elements: earth, air, fire and water.

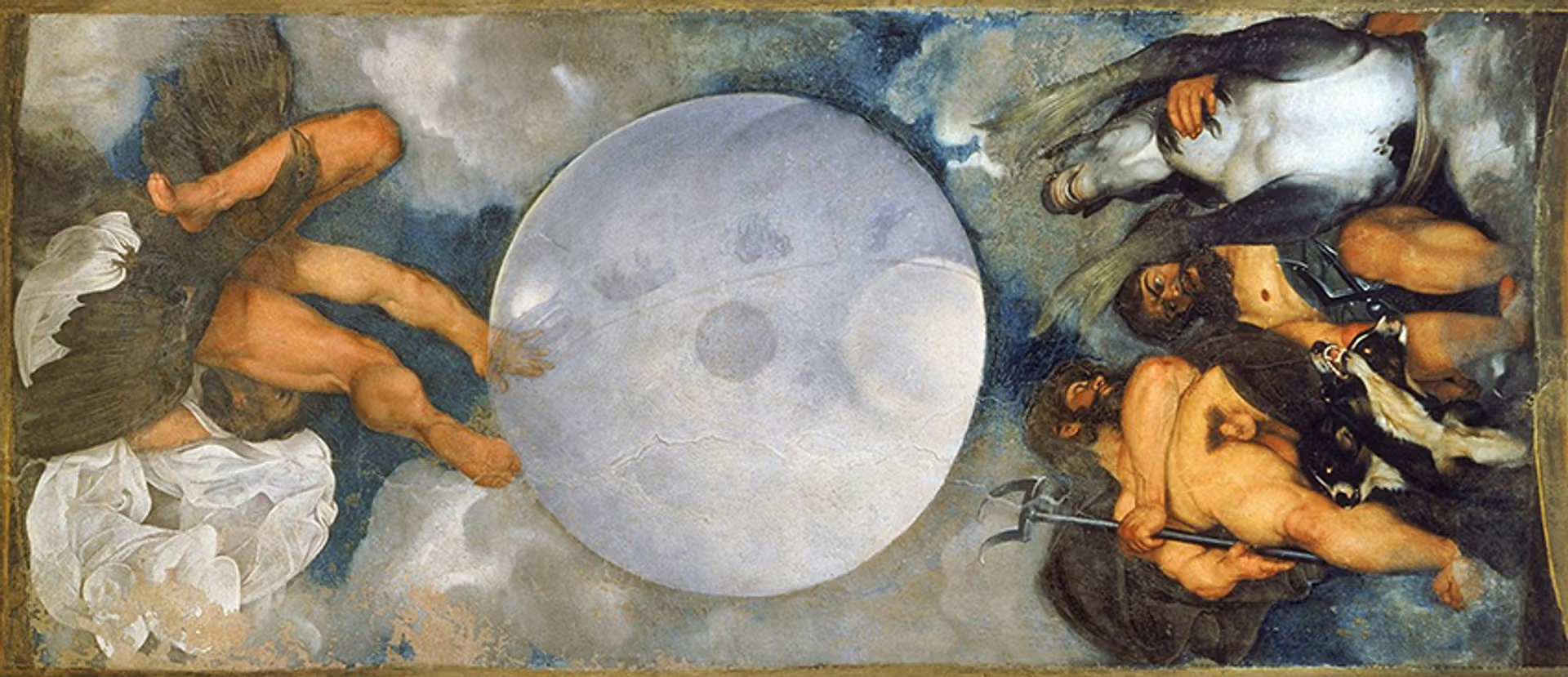

The painting encapsulates this in an astonishing exercise in foreshortening, which led to the belief at the time that Caravaggio painted it to silence critics who said he could not draw except very simply, with a model in front of him. Jove (air and sulphur) sits on the back of an eagle with great spread wings; Pluto (salt and earth) with his three-headed dog Cerberus, is an explicit study of male private parts from beneath; Neptune (water and mercury) embraces a sea horse. In the middle, there is a huge, glowing moon with signs of the Zodiac, alluding to the astrological component of Paracelsus’s thinking.

Caravaggio, Jupiter, Neptune and Pluto (around 1597) in the collection of the Villa Aurora.

Although this painting is well documented, it was only “rediscovered” by art historians in 1967, and now that Caravaggio has become a super-star because of his tragic mysterious end and self-destructive life-story—an outsider, revolutionary realist, gay icon, murderer—it is the part of the Casino’s artistic riches that is getting most publicity, but the building also has another name, the Villa Aurora, because of the outstandingly beautiful fresco in its grandest room.

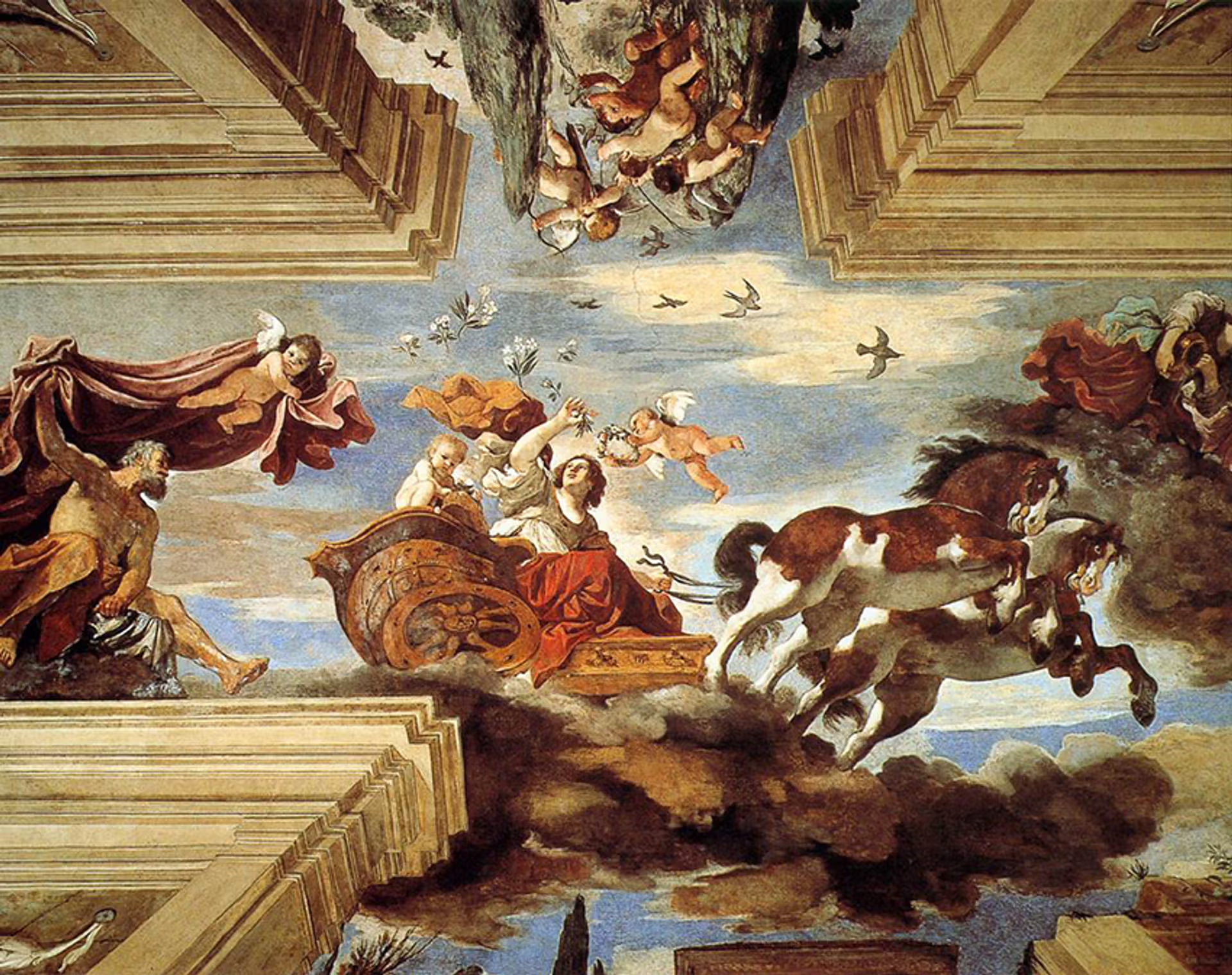

In 1621, Cardinal del Monte sold the casino to the Bolognese nobleman Ludovico Ludovisi, whose uncle was elected Pope Gregory XV that year, so Ludovico employed his countryman Guercino to paint Aurora, that is, the dawn, driving away the night with her chariot, possibly symbolising the beginning of a glorious, new era. It is a masterpiece of illusionism, opening up the room to a trompe l’oeil sky, surrounded by grand, painted arcades and landscapes of great elegance and sophistication by Guercino and other artists.

Whoever buys the Ludovisi Casino can lie back on a sofa and enjoy all this splendour 24 hours a day, but does that justify the huge figures set by the tribunal? Is the Casino’s artistic component worth €300m-400m on top of the price of the property, or zero? The building is valued at €45m, which is high but reasonable, all the rest being attributed to the paintings and sculpture, which have been estimated by Alessandro Zuccari, a professor of art history at Rome’s La Sapienza university. What this academic has not realised is that the market price of a work of art is related to the ease with which it can be resold, preferably at a profit, which is very much not the case with the Ludovisi Casino, because it has been listed by the state as a monument of national importance since 1987. Because of this, the state has the right to buy the property at the price it reaches at auction within 60 days of the sale.

Listed status not only means that nothing may be removed from the building, but the ministry of culture can make regular inspections to see that it is is being looked after according to museum criteria and access is provided to the public. Thus, anyone bidding at this auction has to want to own property in Rome, look after an historic building, and put up with visitors and what could be considerable official interference. This certainly narrows the field, so in valuing the Casino you cannot extrapolate from record prices paid recently for some Old Masters, such as the $92.2m reached by Botticelli’s Portrait of a Young Man with a Roundel at Sotheby’s in January 2021.

Not only that. There is an incentive for potential bidders to sit on their hands because, if the Casino remains unsold, according to the rules of the tribunal, which is more accustomed to selling bankruptcy property such as shops, warehouses and cars, it will be re-offered at a 20% lower starting price, diminishing until it eventually finds a buyer.

The reason why the Casino Ludovisi is being offered by the tribunal rather than a more experienced vendor of art and high-class property, such as Sotheby’s, is that it is the subject of a dispute over the inheritance between the widow of the late Prince Nicolò Boncompagni Ludovisi (d. 2018) and the three sons from his first marriage, and the tribunal has jurisdiction in such cases. By Italian law an inheritance must be divided between the surviving spouse and descendants, which has not only led to the progressive fragmentation of estates and collections, but also endless litigation about how to share out the value of an inheritance fairly.

The widowed princess is Rita Carpenter, born in San Antonio, Texas, married briefly to Congressman John Jenrette. She worked as a political researcher, appeared on Fox TV, featured in Playboy, and her last job before marrying the prince in 2009 was as an estate agent, when she helped Donald Trump buy the General Motors building in Manhattan. She has been responsible for considerable restoration of the Casino Ludovisi and for opening it regularly to the public for the first time in its history, showing how the private ownership of historic properties can be of benefit to the community at no cost to the public purse, a concept that is alien to the Italian way of thinking. The old adage that “The private ownership of art is theft” remains deeply rooted, as shown by a current online petition for the state to buy the Casino Ludovisi, signed by nearly 35,000 people: “Art belongs to all, for all”; “Culture is being sold off”; “This must not disappear into private hands” are typical of the many comments.

The popular cry is for the government to buy the Casino Ludovisi by using some of the EU’s special funding (PNRR) of €233bn aimed at helping Italy rebuild and reform its economy and body politic. This is neither necessary nor desirable. Should any of that money be diverted into cultural channels, there are much more urgent claims on nearly half a billion euro, such as setting up an effective administrative body to plan and begin to deal with the threatened destruction of Venice by sea-level rise, or even just opening the 40 Venetian churches with paintings by artist such as Titian, Tintoretto and Palma Giovane, which are currently closed because the traditional support structures have dwindled away.

As so often in Italy, what is needed is a strategic plan.