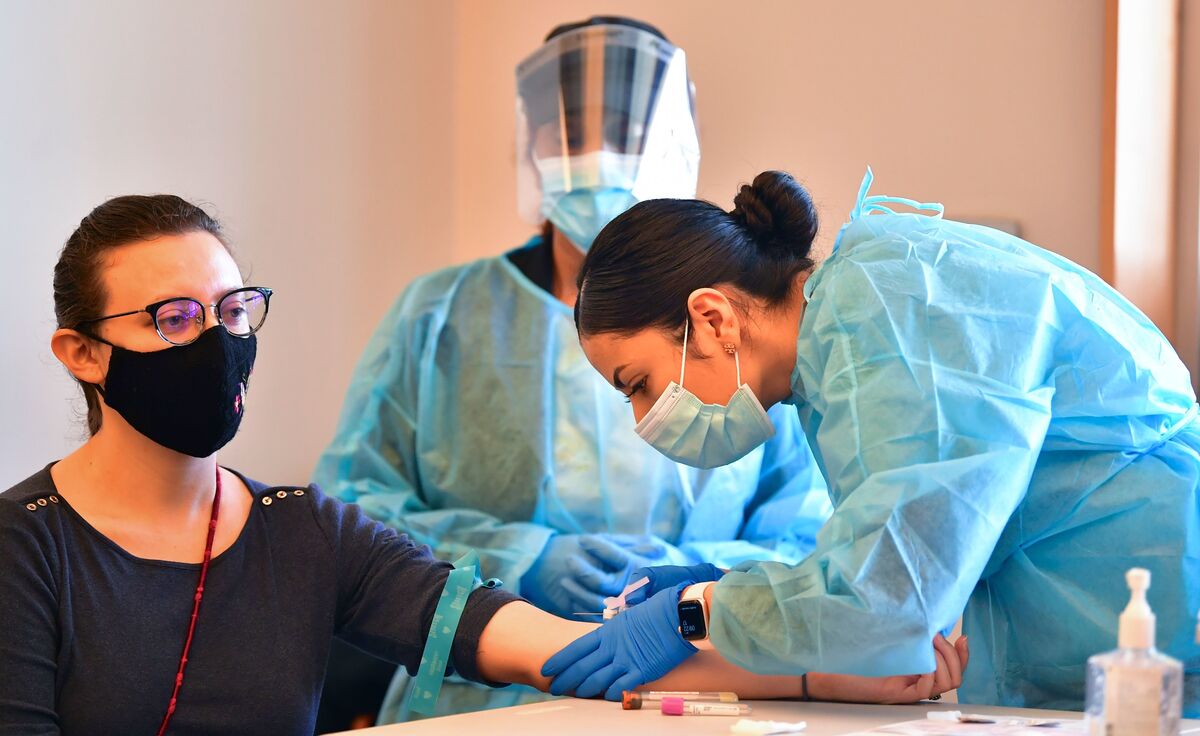

A phlebotomist draws blood at a free COVID-19 antibody testing event on Feb.17 in Pico Rivera, Calif.

Frederic J. Brown=/AFP via Getty Images

hide caption

toggle caption

Frederic J. Brown=/AFP via Getty Images

A phlebotomist draws blood at a free COVID-19 antibody testing event on Feb.17 in Pico Rivera, Calif.

Frederic J. Brown=/AFP via Getty Images

Each week, we answer “frequently asked questions” about life during the coronavirus crisis. If you have a question you’d like us to consider for a future post, email us at goatsandsoda@npr.org with the subject line: “Weekly Coronavirus Questions.” See an archive of our FAQs here.

Q: I’m fully vaccinated. Should I get an antibody test to check my immunity to COVID-19?

A: You might be tempted to take an antibody test to find out whether your COVID vaccine worked. But — no. Immunology experts say there is little to be gained, for now, from an antibody test, for a number of reasons.

Dr. Carl Fitchenbaum, an infectious disease specialist at the University of Cincinnati College of Medicine, says that while there are antibody tests to verify protection from vaccines for diseases such as mumps and measles, “those took decades to develop, and with COVID-19 we’re only at a year and a half.”

Researchers have developed some tests and are working on perfecting them, but more work remains to be done, says Fitchenbaum, and for now the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) does not recommend checking for antibodies after vaccination. Their reasoning includes the fact that, while there are several COVID-19 antibody tests being used by commercial labs, most look for antibodies that are different than the ones produced by the vaccines in use, so they won’t offer much information.

The current COVID-19 vaccines target the SARS-CoV-2 spike protein, so unless the antibody test is looking for antibodies to that protein, the test results will have no meaning. In a recent blog post for the University of Texas, Dr. Luis Ostrosky, head of infectious diseases for the university’s medical school, wrote, “when most people sign up for a test, most laboratories and providers are typically testing for anti-nucleocapsid antibodies. The problem with that is those are not antibodies that would be created by the vaccine, but only through natural infection.” So in other words, many of the antibody tests available now would only be able to tell you whether you have antibodies as a result of getting COVID, and not from having received a vaccine.

Increasingly however, Ostrosky tells NPR, labs are also producing tests that can detect antibodies to the spike protein.

These still are largely too premature to use, says Dr. Peter Hotez, dean of the National School of Tropical Medicine at the Baylor College of Medicine. “The test results will show the number of antibodies the person has to the spike protein, but we have no idea yet how many antibodies a person needs to be protected.”

Labs are currently working on understanding the level of antibodies that indicate protection, says Ostrosky. Since the tests are authorized by the FDA, commercial labs can and are making the tests available to individuals, but for now the tests come without enough context, says Ostrosky. “Someone could have no antibodies, but that doesn’t necessarily mean they have no protection against the virus. It could be that if exposed, other helper cells, such as B and T cells, would come to the rescue as a result of vaccination.”

Hotez says one exception to the advice of not getting tested may be in immunocompromised people who have been vaccinated. Doctors may want “to have at least some indication of whether antibodies are present, if any,” because of the risk to those people of developing COVID-19. “In that case, says Hotez, work with your physician to try to find the spike protein antibody test. “Since protection against SARS-CoV-2 is especially important in people who are immunocompromised, because they are particularly at risk of severe disease and death, having the information on antibodies at least gives us some sense they may be protected,” says Ostrosky. “If an immunocompromised patient does not have antibodies, doctors may consider bolstering their protection with another dose of the vaccine, continued masking and other precautions.”

Some countries, including Israel, are requiring antibody tests to the spike protein as a condition for entering the country, an expense that recently ran one traveler more than $100 at one of the country’s private labs. “But that’s not a measure of how protected you are,” says Dr. Aaron Glatt, chief of infectious diseases at Mount Sinai Nassau South Hospital in Hewlett, N.Y. “Israel is checking to see if you’ve actually been vaccinated, rather than simply relying on people telling them they have been,” says Glatt, “for fear that some vaccination cards might have been falsified.”

Fran Kritz is a health policy reporter based in Washington, D.C., who has contributed to The Washington Post and Kaiser Health News. Find her on Twitter: @fkritz