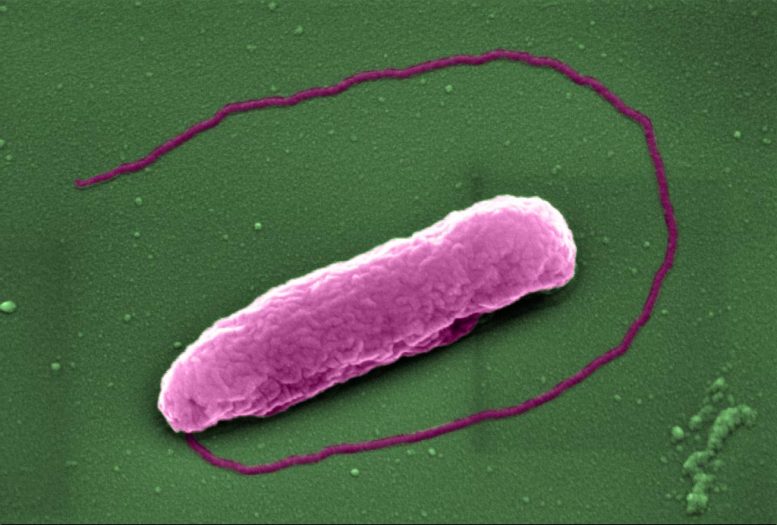

The superbug Pseudomonas aeruginosa, which can cause lung infections in people on ventilators in Intensive Care Units. Credit: Imperial College London

Scientists have revealed how an antibiotic of ‘last resort’ kills bacteria.

The findings, from Imperial College London and the University of Texas, may also reveal a potential way to make the antibiotic more powerful.

The antibiotic colistin has become a last resort treatment for infections caused by some of the world’s nastiest superbugs. However, despite being discovered over 70 years ago, the process by which this antibiotic kills bacteria has, until now, been something of a mystery.

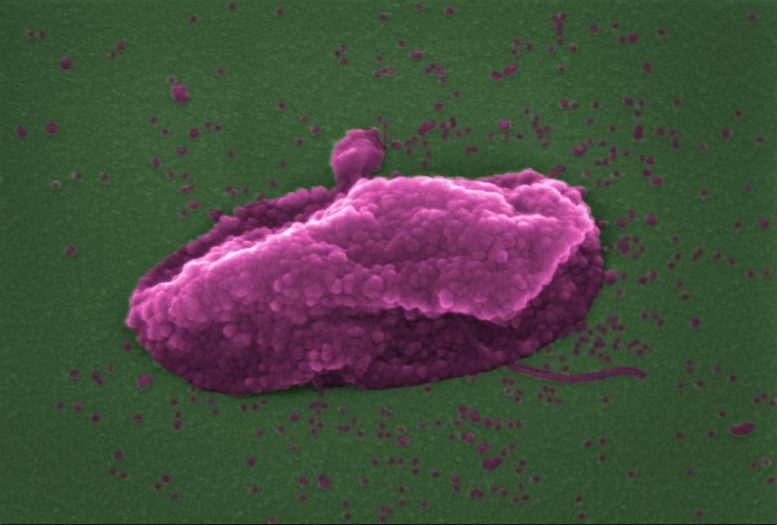

Now, researchers have revealed that colistin punches holes in bacteria, causing them to pop like balloons. The work, funded by the Medical Research Council and Wellcome Trust, and published in the journal eLife, also identified a way of making the antibiotic more effective at killing bacteria.

The superbug Pseudomonas aeruginosa after being ‘popped’ by the antibiotic colistin. Credit: Imperial College London

Colistin was first described in 1947, and is one of the very few antibiotics that is active against many of the most deadly superbugs, including E. coli, which causes potentially lethal infections of the bloodstream, and Pseudomonas aeruginosa and Acinetobacter baumannii, which frequently infect the lungs of people receiving mechanical ventilation in intensive care units.

These superbugs have two ‘skins’, called membranes. Colistin punctures both membranes, killing the bacteria. However, whilst it was known that colistin damaged the outer membrane by targeting a chemical called lipopolysaccharide (LPS), it was unclear how the inner membrane was pierced.

Now, a team led by Dr Andrew Edwards from Imperial’s Department of Infectious Disease, has shown that colistin also targets LPS in the inner membrane, even though there’s very little of it present.

Dr. Edwards said: “It sounds obvious that colistin would damage both membranes in the same way, but it was always assumed colistin damaged the two membranes in different ways. There’s so little LPS in the inner membrane that it just didn’t seem possible, and we were very skeptical at first. However, by changing the amount of LPS in the inner membrane in the laboratory, and also by chemically modifying it, we were able to show that colistin really does puncture both bacterial skins in the same way – and that this kills the superbug. ”

Next, the team decided to see if they could use this new information to find ways of making colistin more effective at killing bacteria.

They focussed on a bacterium called Pseudomonas aeruginosa, which also causes serious lung infections in people with cystic fibrosis. They found that a new experimental antibiotic, called murepavadin, caused a build up of LPS in the bacterium’s inner skin, making it much easier for colistin to puncture it and kill the bacteria.

The team say that as murepavadin is an experimental antibiotic, it can’t be used routinely in patients yet, but clinical trials are due to begin shortly. If these trials are successful, it may be possible to combine murepavadin with colistin to make a potent treatment for a vast range of bacterial infections.

Akshay Sabnis, lead author of the work also from the Department of Infectious Disease, said: “As the global crisis of antibiotic resistance continues to accelerate, colistin is becoming more and more important as the very last option to save the lives of patients infected with superbugs. By revealing how this old antibiotic works, we could come up with new ways to make it kill bacteria even more effectively, boosting our arsenal of weapons against the world’s superbugs.”

Reference: “Colistin kills bacteria by targeting lipopolysaccharide in the cytoplasmic membrane” by Akshay Sabnis, Katheryn LH Hagart, Anna Klöckner, Michele Becce, Lindsay E Evans, R Christopher D Furniss, Despoina AI Mavridou, Ronan Murphy, Molly M Stevens, Jane C Davies, Gérald J Larrouy-Maumus, Thomas B Clarke and Andrew M Edwards, 6 April 2021, eLife.

DOI: 10.7554/eLife.65836