Black Americans experienced highest per capita excess death rates, while regional surges contributed to higher excess death rates from COVID-19 and other causes, a VCU-led Journal of the American Medical Association study finds.

Extended surges in the South and West in the summer and early winter of 2020 resulted in regional increases in excess death rates, both from COVID-19 and from other causes, a 50-state analysis of excess death trends has found. Virginia Commonwealth University researchers’ latest study notes that Black Americans had the highest excess death rates per capita of any racial or ethnic group in 2020.

The research, publishing today (Friday, April 2, 2021) in the Journal of the American Medical Association, offers new data from the last 10 months of 2020 on how many Americans died during 2020 as a result of the effects of the pandemic — beyond the number of COVID-19 deaths alone — and which states and racial groups were hit hardest.

The rate of excess deaths — or deaths above the number that would be expected based on averages from the previous five years — is usually consistent, fluctuating 1% to 2% from year to year, said Steven Woolf, M.D., the study’s lead author and director emeritus of VCU’s Center on Society and Health. From March 1, 2020, to January 2, 2021, excess deaths rose a staggering 22.9% nationally, fueled by COVID-19 and deaths from other causes, with regions experiencing surges at different times.

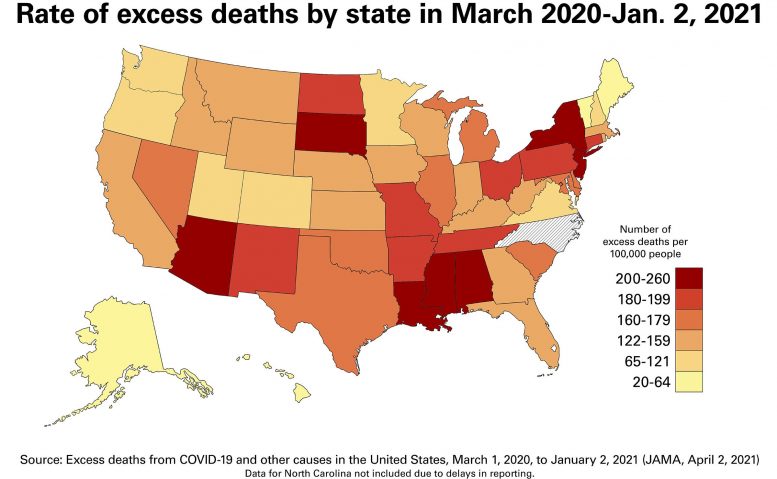

A map of the United States showing the rate of excess deaths. The Dakotas, New England, the South and Southwest had some of the highest excess deaths per 100,000 people during the final 10 months of 2020. Credit: Virginia Commonwealth University

“COVID-19 accounted for roughly 72% of the excess deaths we’re calculating, and that’s similar to what our earlier studies showed. There is a sizable gap between the number of publicly reported COVID-19 deaths and the sum total of excess deaths the country has actually experienced,” Woolf said.

For the other 28% of the nation’s 522,368 excess deaths during that period, some may actually have been from COVID-19, even if the virus was not listed on the death certificates due to reporting issues.

But Woolf said disruptions caused by the pandemic were another cause of the 28% of excess deaths not attributed to COVID-19. Examples might include deaths resulting from not seeking or finding adequate care in an emergency such as a heart attack, experiencing fatal complications from a chronic disease such as diabetes, or facing a behavioral health crisis that led to suicide or drug overdose.

“All three of those categories could have contributed to an increase in deaths among people who did not have COVID-19 but whose lives were essentially taken by the pandemic,” said Woolf, a professor in the Department of Family Medicine and Population Health at the VCU School of Medicine.

The percentage of excess deaths among non-Hispanic Black individuals (16.9%) exceeded their share of the U.S. population (12.5%), reflecting racial disparities in mortality due to COVID-19 and other causes of death in the pandemic, Woolf and his co-authors write in the paper. The excess death rate among Black Americans was higher than rates of excess deaths among non-Hispanic white or Hispanic populations.

Woolf said his team was motivated to break down this information by race and ethnicity due to mounting evidence that people of color have experienced an increased risk of death from COVID-19.

“We found a disproportionate number of excess deaths among the Black population in the United States,” said Woolf, VCU’s C. Kenneth and Dianne Wright Distinguished Chair in Population Health and Health Equity. “This, of course, is consistent with the evidence about COVID-19 but also indicates that excess deaths from some conditions other than COVID-19 are also occurring at higher rates in the African American population.”

Surges in excess deaths varied across regions of the United States. Northeastern states, such as New York and New Jersey, were among the first hit by the pandemic. Their pandemic curves looked like a capital “A,” Woolf said, peaking in April and returning rapidly to baseline within eight weeks because strict restrictions were put in place. But the increase in excess deaths lasted much longer in other states that lifted restrictions early and were hit hard later in the year. Woolf cited economic or political reasons for decisions by some governors to weakly embrace, or discourage, pandemic control measures such as wearing masks.

“They said they were opening early to rescue the economy. The tragedy is that policy not only cost more lives, but actually hurt their economy by extending the length of the pandemic,” Woolf said. “One of the big lessons our nation must learn from COVID-19 is that our health and our economy are tied together. You can’t really rescue one without the other.”

According to the study’s data, the 10 states with the highest per capita rate of excess deaths were Mississippi, New Jersey, New York, Arizona, Alabama, Louisiana, South Dakota, New Mexico, North Dakota and Ohio.

Nationally, Woolf expects the U.S. will see consequences of the pandemic long after this year. For example, cancer mortality rates may increase in the coming years if the pandemic forced people to delay screening or chemotherapy.

Woolf said future illness and deaths from the downstream consequences of the devastated economy could be addressed now by “bringing help to families, expanding access to health care, improving behavioral health services and trying to bring economic stability to a large part of the population that was already living on the edge before the pandemic.” Among other research, his team’s 2019 JAMA study of working-age mortality underscores the importance of prioritizing public health measures like these, he said.

“American workers are sicker and dying earlier than workers in businesses in other countries that are competing against America,” Woolf said. “So investments to help with health are important for the U.S. economy in that context just as they are with COVID-19.”

Derek Chapman, Ph.D., Roy Sabo, Ph.D., and Emily Zimmerman, Ph.D., of VCU’s Center on Society and Health and the School of Medicine joined Woolf as co-authors on the paper published Friday, “Excess Deaths From COVID-19 and Other Causes in the United States, March 1, 2020, to January 2, 2021.”

Their study also confirms a trend Woolf’s team noted in an earlier 2020 study: Death rates from several non-COVID-19 conditions, such as heart disease, Alzheimer’s disease and diabetes, increased during surges.

“This country has experienced profound loss of life due to the pandemic and its consequences, especially in communities of color,” said Peter Buckley, M.D., dean of the VCU School of Medicine. “While we must remain vigilant with social distancing and mask-wearing behaviors for the duration of this pandemic, we must also make efforts to ensure the equitable distribution of care if we are to reduce the likelihood of further loss of life.”

Based on current trends, Woolf said the surges the U.S. has seen might not be over, even with vaccinations underway.

“We’re not out of the woods yet because we’re in a race with the COVID-19 variants. If we let up too soon and don’t maintain public health restrictions, the vaccine may not win out over the variants,” Woolf said. “Unfortunately, what we’re seeing is that many states have not learned the lesson of 2020. Once again, they are lifting restrictions, opening businesses back up, and now seeing the COVID-19 variants spread through their population.

“To prevent more excess deaths, we need to hold our horses and maintain the public health restrictions that we have in place so the vaccine can do its work and get the case numbers under control.”

Reference: 2 April 2021, JAMA.

DOI: 10.1001/jama.2021.5199

Funding: National Center for Advancing Translational Sciences (division of National Institutes of Health), National Institute on Aging (division of National Institutes of Health)