As the world continued to grapple with changing restrictions and recommendations surrounding the coronavirus pandemic, rumors persisted into late summer 2020 regarding scientific understanding behind the effectiveness of certain face coverings used to reduce COVID-19 transmission. In August, a number of news publications reported findings from Duke University research and claimed wearing “neck gaiters” — stretchy, thin articles of clothing worn around the neck to sometimes cover the face — can be worse for transmission than foregoing a mask altogether.

Our research found this claim to be false and largely misreported by some media outlets.

The claim can be traced back to a study published in Science Advances on Aug. 7, 2020. Throughout the course of their research, scientists set out to determine the best methods for testing how to evaluate 14 types of face coverings — not determine which one is the most effective in protecting against transmission. The study was not meant to be a conclusive guide describing which masks to wear, but rather how to test their varied effectiveness. Results regarding the effectiveness of any particular face covering were merely a byproduct of the study.

A simple and cost-effective method for testing the efficacy of certain face coverings is thought to be a crucial element to furthering the understanding of how SARS-CoV-2, the coronavirus responsible for COVID-19, is spread. To that end, the research team turned to optical imaging in order to “highlight stark differences in the effectiveness of different masks and mask alternatives” that may help stop the spread of respiratory droplets, which are known to contain SARS-CoV-2 and can transmit during “regular speech.”

Furthermore, as of mid-2020, there was still much to be determined about the infection pathways of COVID-19, the route of transmission, how to properly use a mask, and how the virus may be affected by environmental variables.

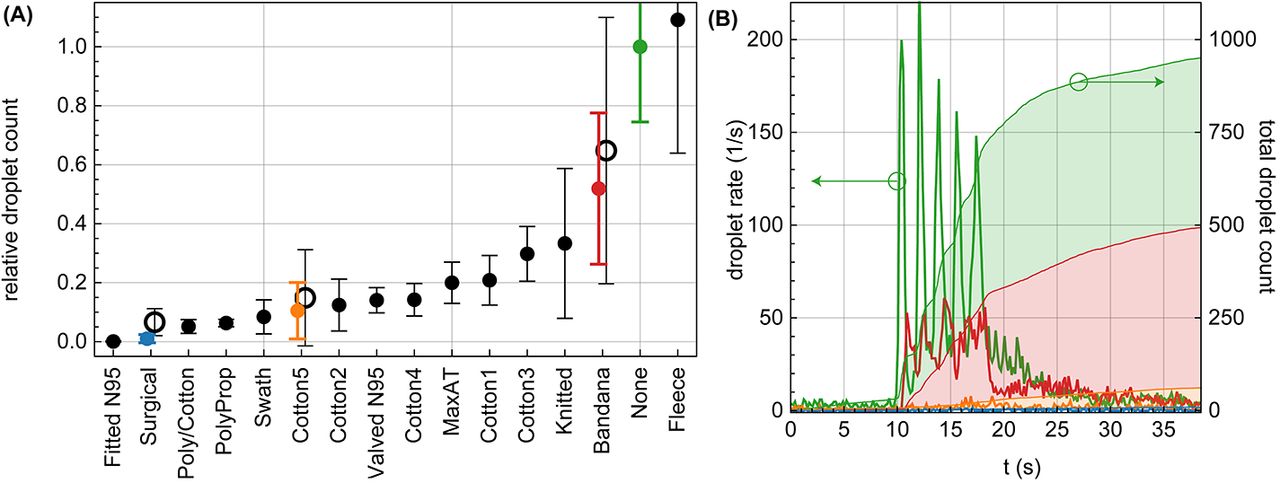

For the proof-of-concept study, which is meant to inform future research, a person wearing a mask stood inside of a dark enclosure and spoke into the direction of a laser beam. Respiratory droplets were visible as they scattered light from the laser beam that a cell phone camera recorded. A simple computer algorithm then counted the droplets. Masks tested included a fitted N95 mask both with and without valves, surgical masks, different variations of polyester or cotton masks, as well as a bandana, and neck fleece, or gaiter. These were then compared against respiratory droplets emitted by a person who wore no face covering.

In short, the study findings concluded that the laser-beam method for viewing, recording, and counting respiratory droplets from analyzed face coverings is a quick and easy way to test their effectiveness. But how well each mask worked was not determined —– that would require further, more specific, evaluation, stricter testing mechanisms, and greater control over variables. Now, other scientists can use this same laser-beam method to specifically test for mask effectiveness.

A fitted N95 mask was determined to be the most effective, since just .1% of droplets were transmitted. A gaiter, on the other hand, was shown to disperse larger droplets into smaller ones, resulting in a higher droplet count than any other face covering and, indeed, than even foregoing a face mask altogether.

“We noticed that speaking through some masks (particularly the neck fleece) seemed to disperse the largest droplets into a multitude of smaller droplets, which explains the apparent increase in droplet count relative to no mask in that case,” wrote the researchers. “Considering that smaller particles are airborne longer than large droplets (larger droplets sink faster), the use of such a mask might be counterproductive.”

Katherine Ellen Foley, a health and science reporter at Quartz, pointed out in a Twitter thread that the research is not without limitations. For starters, test subjects were just talking and not sneezing, coughing, or breathing heavily. Furthermore, the study counted the number of droplets transmitted through each mask — a finding that does not necessarily equate to risk. In all, the research was meant to inform attempts to improve training on proper mask use to determine the safety and efficacy of reusing some masks.

“This was just a demonstration — more work is required to investigate variations in masks, speakers, and how people wear them — but it demonstrates that this sort of test could easily be conducted by businesses and others that are providing masks to their employees or patrons,” said study author Martin Fischer, Ph.D., a chemist and physicist and director of the Advanced Light Imaging and Spectroscopy facility, in a Duke University news release.

Then there is the argument regarding mask material. The researchers only tested gaiters made from fleece. However, different fabrics or materials — like polyester or cotton — could influence how effective a gaiter is in reducing transmission.

Outside experts contended headlines misrepresented the findings by saying that it’s better to wear no mask than a neck gaiter. The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention recommends that people wear masks in public settings and when around people outside of their household, citing evidence that masks are effective in reducing the transmission of COVID-19 and spray of droplets when worn over the nose and mouth.

“If everyone wore a mask, we could stop up to 99% of these droplets before they reach someone else,” said Duke University physician Eric Westman. “In the absence of a vaccine or antiviral medicine, it’s the one proven way to protect others as well as yourself.”